2020: The Year in Horror

2020 has been routinely called the worst year in living memory. As if every aspect of it--the pandemic, the absurd anti-democratic antics of Trump, the blind denial of both systemic racism and the validity of science by half the populace--weren't ugly enough, the Fates decreed 2020 was a leap year with one extra, freakin' day! Burdened with an unjust destiny, I'm more likely to work out my pain by making stuff than crying about it. This was the year I saved my tears for moments containing common decency and grace; alternately, here's some stuff I posted.

For the Lower Merion Township "New Year's at Noon" event, I built a two-stage prop, loaded with twenty pounds of chocolate, that was supposed to represent a pair of spectacles with a 20/20 view of the coming months. Instead it hinted at the calamities to come: a beaming fireman dropped one lens, and as the little kiddies leapt for the splattering goodies, he let the other lens fly. Wholesale murder was averted by mere inches. Soothsayer Cato's political prediction proved a total bust; however, the little fellow who steps into frame behind the marionette in this video became a local hero come July when he led our neighborhood Black Lives Matter demonstration.

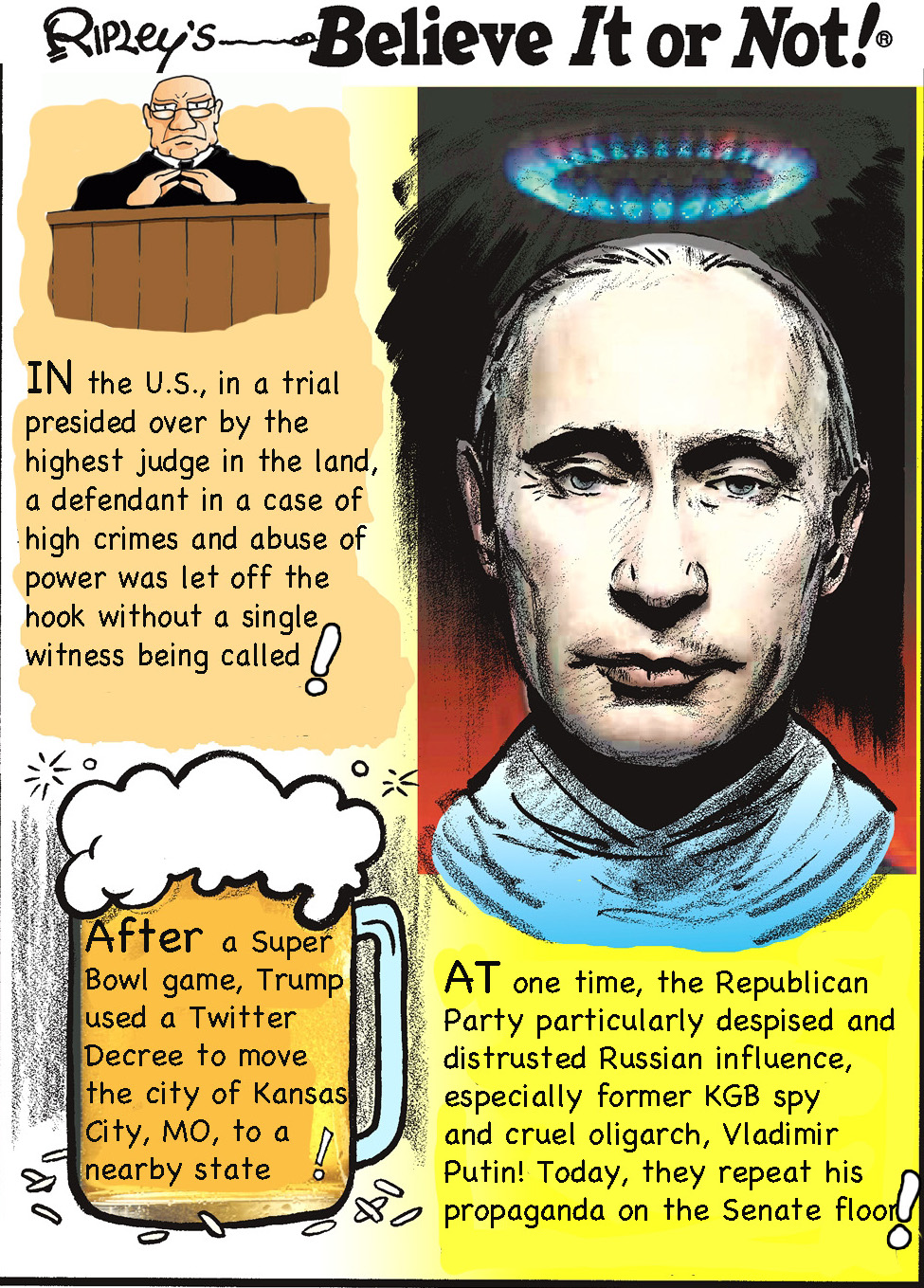

As Covid-19 spread from China to the Mid-East and Europe, I was still fuming over  the dereliction of Mitch McConnell and Conservatives during Trump's mockery of a Senate impeachment trial. Republicans admitted their chief gangster had withheld funds designated by Congress to assist Ukraine in defending the Crimean Peninsula from Russian invaders, but they refused to allow that trading government favors for dirt on a political opponent rose to the level of "high crimes and misdemeanors." The senate majority leadership would not even allow the many dedicated, civil servant witnesses to Trump's blatant corruption a hearing on the Senate floor.

the dereliction of Mitch McConnell and Conservatives during Trump's mockery of a Senate impeachment trial. Republicans admitted their chief gangster had withheld funds designated by Congress to assist Ukraine in defending the Crimean Peninsula from Russian invaders, but they refused to allow that trading government favors for dirt on a political opponent rose to the level of "high crimes and misdemeanors." The senate majority leadership would not even allow the many dedicated, civil servant witnesses to Trump's blatant corruption a hearing on the Senate floor.

Meanwhile, anyone who attended NPR's description of the viral epidemic that shut down China's Wuhan Province knew by January that sucker was going to travel the globe and America should be ready for it. Trump had already tried to shut down the straight-as-an-arrow national public broadcasting service because of its political reporting. His "plan" for dealing with the coming pandemic was to dismiss the validity of science-based reporting as "fake news" and to groundlessly and incompatibly accuse China of somehow fabricating Covid-19 to attack the U.S. and more importantly himself.

Along with the excruciating train wreck of Trump's autocracy came the rank indecency and incompetence of his advisors and appointees. After selling himself to the preposterously gullible American rube as some kind of businessman genius  who would surround himself with "only the best people," Trump appointed lackeys without resumés or conscience to his magician's cabinet. In January, we had Mike Pompeo swearing out the side of his mouth that the administration never received crucial intelligence Putin had put a bounty on the heads of U.S. troops in Afghanistan. Always willing to abet his boss's unholy subordination to the will of the Kremlin, Attorney General William Barr had delivered a totally misleading Sparks Notes version of the Mueller report the previous summer, dismissing concrete evidence of conspiracy and about a dozen counts of obstruction as nothing-to-see-here-people inconsequence. By early 2020, the AG appointed an independent counsel to investigate the origins of the Mueller investigation, fueling the perception of those same dupable Americans that Trump was the poor victim of persecution by a vast, deep-state, Liberal conspiracy.

who would surround himself with "only the best people," Trump appointed lackeys without resumés or conscience to his magician's cabinet. In January, we had Mike Pompeo swearing out the side of his mouth that the administration never received crucial intelligence Putin had put a bounty on the heads of U.S. troops in Afghanistan. Always willing to abet his boss's unholy subordination to the will of the Kremlin, Attorney General William Barr had delivered a totally misleading Sparks Notes version of the Mueller report the previous summer, dismissing concrete evidence of conspiracy and about a dozen counts of obstruction as nothing-to-see-here-people inconsequence. By early 2020, the AG appointed an independent counsel to investigate the origins of the Mueller investigation, fueling the perception of those same dupable Americans that Trump was the poor victim of persecution by a vast, deep-state, Liberal conspiracy.

Because of the power of his office and his willingness to wield it to punish Trump's political enemies  and protect his crooked friends, Attorney General Barr was a particularly galling facet of the most corrupt presidential administration in U.S. history. My reaction was to characterize him as Simon Bar Sinister, arch-enemy of Underdog, the 60s cartoon defender of truth and justice. Later, I put his doughy mug on a mock billboard with the slogan "Better Call Barr," advertising a corrupt legal defense lawyer and emulating a gag used in the Breaking Bad spin-off, starring Bob Odenkirk.

and protect his crooked friends, Attorney General Barr was a particularly galling facet of the most corrupt presidential administration in U.S. history. My reaction was to characterize him as Simon Bar Sinister, arch-enemy of Underdog, the 60s cartoon defender of truth and justice. Later, I put his doughy mug on a mock billboard with the slogan "Better Call Barr," advertising a corrupt legal defense lawyer and emulating a gag used in the Breaking Bad spin-off, starring Bob Odenkirk.

A continuing frustration with the horrible year was the utter disregard for facts among Trumpasites in MAGAland. They were willing to dismiss evidence in Trump's strongarming of Ukraine.  They believed unsubstantiated drivel about Covid-19 blared at them on Fox television and on the completely fanciful Qanon website and Twitter feed, our modern Cloudcuckooland. They believed in corrupt dirty dealing by Hunter and Joe Biden that even Barr refused to prosecute, while the nepotism and graft benefitting Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner was out in the open and in your face.

They believed unsubstantiated drivel about Covid-19 blared at them on Fox television and on the completely fanciful Qanon website and Twitter feed, our modern Cloudcuckooland. They believed in corrupt dirty dealing by Hunter and Joe Biden that even Barr refused to prosecute, while the nepotism and graft benefitting Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner was out in the open and in your face.

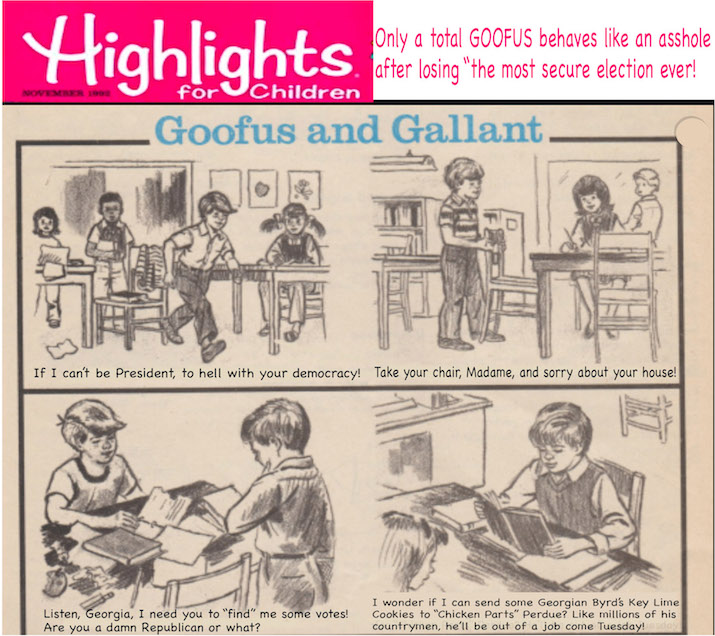

The worst effects of the American public's utter inability to discern factual reporting from propaganda were to come much later in 2020, after Biden won the presidency by 74 electoral votes and seven million popular votes. Three-quarters of Republicans, it would be reported, believed the election was stolen, a conspiracy of mind-boggling vastness, involving Republican election officials in key swing states, which managed to simultaneously dump millions of fraudulent ballots into the system for the Democratic presidential candidate and install new Republican congresspersons and re-vesting Republican Senators down-ticket. The poison of Trump's habitual, conman's flimflam, the line of bull that had kept his hospitality businesses afloat despite six bankruptcies, not only destroyed the democratic norms of 230 years, it eroded standards of logical argument and rudimentary scholarship that had been in Western practice for millennia.

Eventually, Trump initiated a Coronavirus task force and began daily televised briefings,  scattershot affairs where social distancing and masks were neither recommended to every American or employed by the team on the dais. Trump frequently contradicted or stifled his own medical experts, and the American people--desperate for guidance--were subjected to alternative facts from illegitimate "experts" like the My Pillow guy, a major Trump donor.

scattershot affairs where social distancing and masks were neither recommended to every American or employed by the team on the dais. Trump frequently contradicted or stifled his own medical experts, and the American people--desperate for guidance--were subjected to alternative facts from illegitimate "experts" like the My Pillow guy, a major Trump donor.

In contrast to these daily debacles, New York Governor Cuomo was becoming a kind of cult figure with his regular reassurances to the public, which were steeped in science and statistics and cold, hard truth, designed to talk the people of the Empire State through a weeks-long crisis of out-of-control infections, overburdened medical facilities, and grief. New York City was in a lockdown mode, struggling to get ventilators and PPE equipment. In the absence of any co-ordinated federal response to the now-raging pandemic, hard-hit states were on their own, bidding against each other for scarce supplies, subject to price-gouging by vendors, and belittled by Trump who responded to criticism by calling the disaster a "blue state" problem, "not my table."

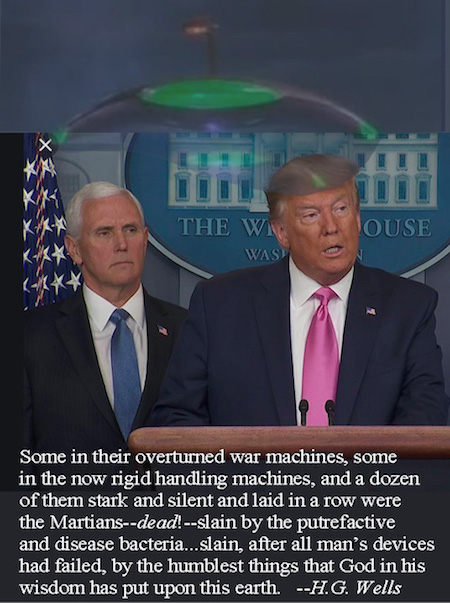

Because the ramifications of the mishandling of the pandemic were obvious  to responsible journalists, the dangers to life and the national economy were obvious to me. One of the first things I realized was that, after Adam Schiff, scores of patriotic and serious-minded witnesses, and a Mitch McConnell-rigged impeachment process had failed to rid the country of the enemy of the state, DeeJay Death Trumpet, the likelihood was a lowly virus would unravel his presidency and put an end to the dismantling of our democracy. I thought of the climax of H.G. Wells' War of the Worlds and the George Pal movie that was one of my childhood favorites.

to responsible journalists, the dangers to life and the national economy were obvious to me. One of the first things I realized was that, after Adam Schiff, scores of patriotic and serious-minded witnesses, and a Mitch McConnell-rigged impeachment process had failed to rid the country of the enemy of the state, DeeJay Death Trumpet, the likelihood was a lowly virus would unravel his presidency and put an end to the dismantling of our democracy. I thought of the climax of H.G. Wells' War of the Worlds and the George Pal movie that was one of my childhood favorites.

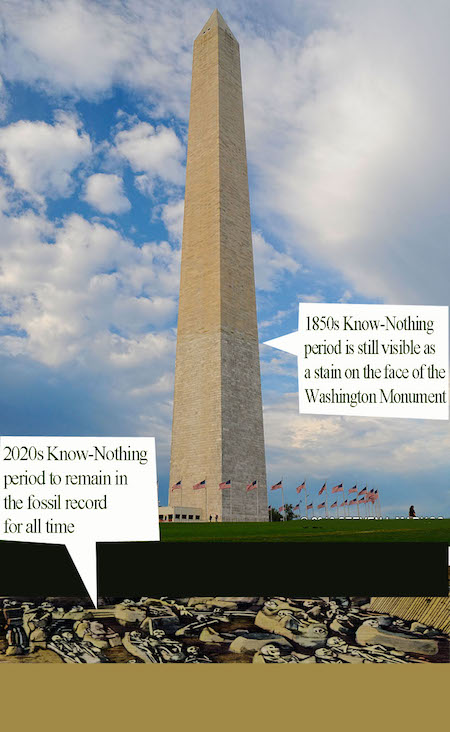

I also considered how the anti-science/alternative facts strain driving at least a third of popular opinion was reminiscent of another dark period in American history, when the "Know-Nothing" party held sway. They also believed in conspiracy theories over fact: one of their favorites was the belief in a conspiracy orchestrated by the Catholic Church to subvert U.S. democracy. They were xenophobic, populist, and prone to demagoguery, since bullying is an alternative to changing people's minds with concrete argument. A permanent stain on the middle of the otherwise pristine white marble exterior of the Washington Monument corresponds to the Know-Nothing period, when the folks who morphed into the Ku Klux Klan after the Civil War controlled much of political activity. I envisioned there would be some gruesome, permanent records, too, of the Trump years--when America lost its ever-loving mind.

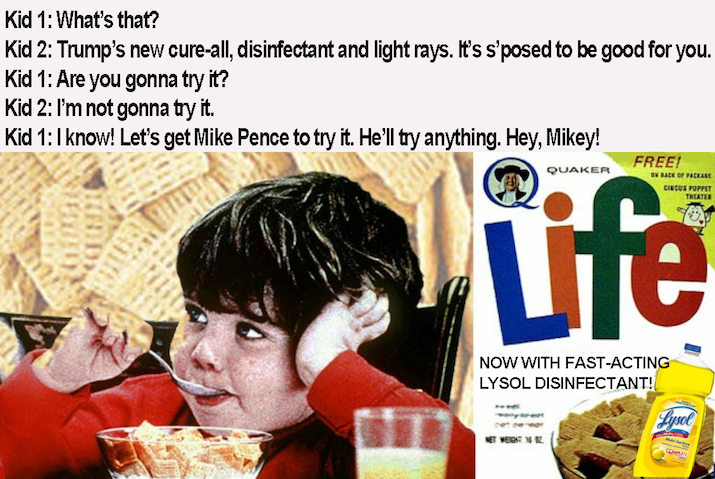

Trump's daily briefings continued into April and were often tragicomic displays of dysfunction, prevarication, and pathetic self-congratulation. He repeated over and over again how great his response to the virus had been, and how the U.S. had more testing than any other country. He ignored the fact that our rate of infection and percentage of cases worldwide was huge considering our percentage of the world's population. The United States had more sickness due to Covid-19 than any country on the planet. Brazil, Russia, and  India were the next nations vying with us for worst-in-show pandemic response, and those three countries were also run by autocratic demagogues. All the while, Trump complained that we only had so many cases because we did so many tests (?!), and one day the whole thing would be over "like magic." Soon after he suggested people might get cured by injection with bleach or suffusion with ultraviolet rays, advisors convinced Trump his daily briefings weren't boosting his public image, and like magic THEY disappeared.

India were the next nations vying with us for worst-in-show pandemic response, and those three countries were also run by autocratic demagogues. All the while, Trump complained that we only had so many cases because we did so many tests (?!), and one day the whole thing would be over "like magic." Soon after he suggested people might get cured by injection with bleach or suffusion with ultraviolet rays, advisors convinced Trump his daily briefings weren't boosting his public image, and like magic THEY disappeared.

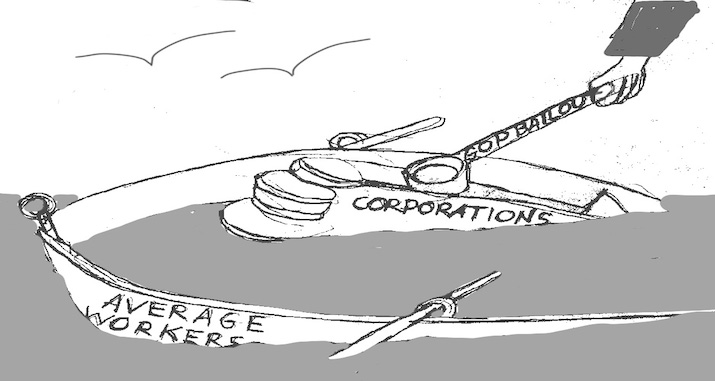

At the end of March, the two-trillion-dollar CARES Act was voted into law, a massive infusion of much needed capital for businesses and relief to families disrupted by the pandemic. The package made perfect sense but it was rife with administrative problems, and the rhetoric from Republicans who flatly refused to support the working class was reason to despair. McConnell and others complained that extending  subsistence-level unemployment benefits to poor families would destroy their incentive to work, and he wanted lawsuit protections for businesses that insisted their employees report to work under life-threatening conditions. People waited months for their relief checks to arrive, and Trump insisted every one of them had his signature on it. After trying to maintain personal oversight of the aid package, Trump fired the Inspector General who was actually charged with the job. According to the Brookings Institute, over 10 billion dollars was handed over to lobbyists and fundraisers connected to Trump and businesses owned or connected to Jared Kushner. Betsy Devos managed to divert public tax dollars to Christian private schools, and even the Catholic Church took a 1.4 billion dollar slice of the pie. Who knew they were so close to collapse?

subsistence-level unemployment benefits to poor families would destroy their incentive to work, and he wanted lawsuit protections for businesses that insisted their employees report to work under life-threatening conditions. People waited months for their relief checks to arrive, and Trump insisted every one of them had his signature on it. After trying to maintain personal oversight of the aid package, Trump fired the Inspector General who was actually charged with the job. According to the Brookings Institute, over 10 billion dollars was handed over to lobbyists and fundraisers connected to Trump and businesses owned or connected to Jared Kushner. Betsy Devos managed to divert public tax dollars to Christian private schools, and even the Catholic Church took a 1.4 billion dollar slice of the pie. Who knew they were so close to collapse?

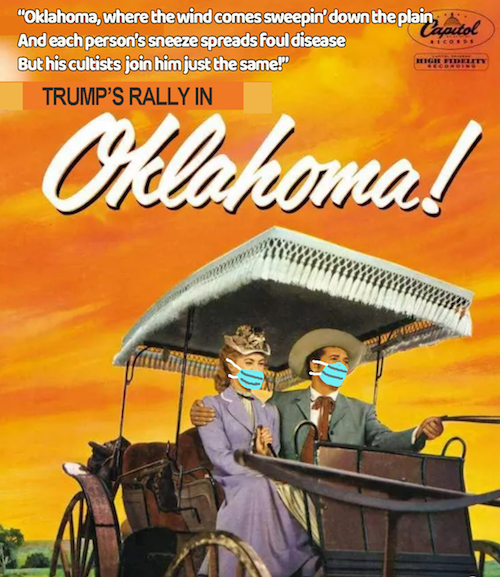

The great failure of the U.S. pandemic response was not having a federally mandated lockdown every place with significant Covid cases and keeping restrictions in effect until the rising curve of infections was flattened, state by state. What we got was a gutless leader who refused to wear a mask, held superspreader rallies where he mocked caution, and continuously wailed that the cure for the pandemic shouldn't be worse than the disease. All Trump cared about was preserving his weak-ass economy to win himself a second term; the Texas lieutenant-governor and others chimed in that elderly people should be happy to sacrifice themselves to the virus to preserve our business health.

What we got was a gutless leader who refused to wear a mask, held superspreader rallies where he mocked caution, and continuously wailed that the cure for the pandemic shouldn't be worse than the disease. All Trump cared about was preserving his weak-ass economy to win himself a second term; the Texas lieutenant-governor and others chimed in that elderly people should be happy to sacrifice themselves to the virus to preserve our business health.

Taking their cue from the science-denier-in-chief, protesters in states like Pennsylvania and Michigan assembled, heavily armed, in state capitals, demanding that all health restrictions be lifted, refusing to be masked, claiming the better good was a violation of their rights and freedoms. The Wisconsin supreme court repealed sensible measures to preserve public safety, likening precautions that protected lives to totalitarianism. Pennsylvania's Republican legislature voted away Governor Wolf's quarantine provisions and restrictions on businesses.

I posted a graphic showing a coronavirus assaulting a nostril. "Are you trying to infect me?"

I posted a graphic showing a coronavirus assaulting a nostril. "Are you trying to infect me?"

"Don't worry. It's only political."

The unprecedented horror of the Trump Virus was that our national dialogue about safety and recovery was warped by our leader's inability to heed indifferent facts and data without rejecting them as some kind of personal attack. News sources were full of anecdotes about perfectly reasonable persons assaulted and ridiculed for wearing masks to protect themselves and the community. Covid-19 has a measurable pathology; unfortunately, our leader in the struggle against it was also pathological.

As 2020 crawled near to the end of summer, the presidential election became increasingly  relevant, and with polls consistently showing Biden carrying an eight- or nine-point lead, my wife and I began to hope we wouldn't need to sell our home and move to whatever foreign nation might still accept Americans in 2021. As the nation burned, President Nero fiddled around at superspreader rallies in Oklahoma, Colorado, and at Mt. Rushmore, salving his colossal ego. A mystery is what compelled his followers to sit masklessly without social distancing, in the middle of a pandemic, and listen to that weak-minded fogey prattle inarticulately that only he could save America--from the crisis his own incompetence had caused. One explanation was that Trump's "What, me worry?" governance appealed to Whites who were in denial about the other disease threatening our democracy: systemic racism.

relevant, and with polls consistently showing Biden carrying an eight- or nine-point lead, my wife and I began to hope we wouldn't need to sell our home and move to whatever foreign nation might still accept Americans in 2021. As the nation burned, President Nero fiddled around at superspreader rallies in Oklahoma, Colorado, and at Mt. Rushmore, salving his colossal ego. A mystery is what compelled his followers to sit masklessly without social distancing, in the middle of a pandemic, and listen to that weak-minded fogey prattle inarticulately that only he could save America--from the crisis his own incompetence had caused. One explanation was that Trump's "What, me worry?" governance appealed to Whites who were in denial about the other disease threatening our democracy: systemic racism.

Say what you will about the destructiveness of the internet and social media, the lies, misinformation and hate speech they proliferate, I believe the appalling injustices fomented by America's blatant and latent racism were finally acknowledged as a result of so many self-satisfied white citizens witnessing George Floyd's murder in broad daylight on the pavement in Minneapolis. In my tiny suburb of Philadelphia, an eight-year-old kid, who refused to accept his black friend might be shot down at some point due solely to race, organized our local Black Lives Matter demonstration.

Hundreds of protests broke out in cities across the nation and where other instances of police brutality occurred. Despicably, Trump incited violent clashes by refusing to acknowledge the racial travesties that have scarred our land since Columbus landed. Instead, he played to the racism of his white base by blowing his "law and order" dog whistle, claiming leftist agitators were the source of sporadic violence that marred many peaceful protests, and declaring he'd send government troops into urban areas to keep the peace if Democratic mayors didn't have the guts to crack down on freedom of speech and the right to assemble.

Hundreds of protests broke out in cities across the nation and where other instances of police brutality occurred. Despicably, Trump incited violent clashes by refusing to acknowledge the racial travesties that have scarred our land since Columbus landed. Instead, he played to the racism of his white base by blowing his "law and order" dog whistle, claiming leftist agitators were the source of sporadic violence that marred many peaceful protests, and declaring he'd send government troops into urban areas to keep the peace if Democratic mayors didn't have the guts to crack down on freedom of speech and the right to assemble.

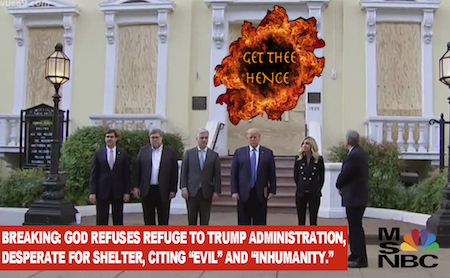

Trump's worst impulses were on display when he used rubber bullets and pepper spray to disperse a peaceful protest next to the White House so that he, Barr, and Kaleigh McEninny could stand in front of a boarded up Episcopal church and hold a Bible upside down for a photograph. Other than that, Trump had stayed holed up in a bunker and ordered an ugly, supplemental wall to be built around "his" house, the only effective physical barrier he had actually erected for the whole of his term in office despite his election promise to keep foreigners from swarming our southern border.

Trump's worst impulses were on display when he used rubber bullets and pepper spray to disperse a peaceful protest next to the White House so that he, Barr, and Kaleigh McEninny could stand in front of a boarded up Episcopal church and hold a Bible upside down for a photograph. Other than that, Trump had stayed holed up in a bunker and ordered an ugly, supplemental wall to be built around "his" house, the only effective physical barrier he had actually erected for the whole of his term in office despite his election promise to keep foreigners from swarming our southern border.

I never found the belief that Trump was an intelligent strategist ("Some people like to say I'm a 'stable genius'") even remotely plausible. Tax records show that his only profitable endeavor against decades of business losses was his long-running reality TV show, where he masqueraded as a shrewd businessman. The wizard-like masters of finance and investment don't market themselves as a brand on coarse television products; they shun the limelight and protect themselves. What Trump has always been is a crude, bullying, inveterate liar, more like a genus that should be kept in a stable. Mostly he has his way with people because his knack for tossing blatant horse hockey takes them off guard. Who would ever expect the most powerful man on the planet to be so nakedly full of shit? Watching him in interviews touting his performance on a simple Alzheimer's screening and claiming the doctors never saw anything like it, one couldn't but notice his desperation to be thought intelligent.

I never found the belief that Trump was an intelligent strategist ("Some people like to say I'm a 'stable genius'") even remotely plausible. Tax records show that his only profitable endeavor against decades of business losses was his long-running reality TV show, where he masqueraded as a shrewd businessman. The wizard-like masters of finance and investment don't market themselves as a brand on coarse television products; they shun the limelight and protect themselves. What Trump has always been is a crude, bullying, inveterate liar, more like a genus that should be kept in a stable. Mostly he has his way with people because his knack for tossing blatant horse hockey takes them off guard. Who would ever expect the most powerful man on the planet to be so nakedly full of shit? Watching him in interviews touting his performance on a simple Alzheimer's screening and claiming the doctors never saw anything like it, one couldn't but notice his desperation to be thought intelligent.

Times of great stress reveal the true nature of people. 2020 betrayed Trump's character to enough who had been blind to it that he lost re-election. He claimed he'd aced the pandemic response, that he regretted nothing. When members of the White House staff and inner circle began to contract Covid following reckless behavior and a party for newly appointed justice Amy Coney "Mony Mony" Barrett, people who had believed the misinformation diminishing it on Fox News began to suspect that the disease was a very real threat to everyone and the shameless bluster of the Trump Troupe was juvenile. The moment we'd all been waiting for happened just after the first presidential debate, when Trump himself grew short of breath, weak, and even more unfit for office than on a typical day. He was flown to Walter Reed hospital in a helicopter.

Times of great stress reveal the true nature of people. 2020 betrayed Trump's character to enough who had been blind to it that he lost re-election. He claimed he'd aced the pandemic response, that he regretted nothing. When members of the White House staff and inner circle began to contract Covid following reckless behavior and a party for newly appointed justice Amy Coney "Mony Mony" Barrett, people who had believed the misinformation diminishing it on Fox News began to suspect that the disease was a very real threat to everyone and the shameless bluster of the Trump Troupe was juvenile. The moment we'd all been waiting for happened just after the first presidential debate, when Trump himself grew short of breath, weak, and even more unfit for office than on a typical day. He was flown to Walter Reed hospital in a helicopter.

Unsurprisingly, Trump spokespeople refused to say when he had been last tested or knew he was infectious. He may have exposed Joe Biden to the virus during the debate, days before he became symptomatic. Trump's children had themselves appeared maskless at the event, casually flaunting Cleveland Clinic guidelines. Chris Christie, who "prepped" Trump for the big debate match-up, also fell ill and was in an ICU bed for more than a week.

Seeing Trump in the hospital for four days was a surreal spectacle, indeed. Here he was, getting experimental treatment available only to a very few, but his personal doctor, Sean Conley, D.O., refused to level with the American people about the severity of the patient's condition or how much oxygen he had been given. One certainty was that Trump was pumped up with steroids. His behavior for days was manic even for him: in the middle of intensive treatment and while still infectious he rode in the presidential limousine past supporters who were camped outside Walter Reed Medical Center (maskless, of course) to give them a thrill and to bask in the waves of irrational adoration to which he was addicted. The adventure needlessly exposed Secret Service agents to Covid.

Seeing Trump in the hospital for four days was a surreal spectacle, indeed. Here he was, getting experimental treatment available only to a very few, but his personal doctor, Sean Conley, D.O., refused to level with the American people about the severity of the patient's condition or how much oxygen he had been given. One certainty was that Trump was pumped up with steroids. His behavior for days was manic even for him: in the middle of intensive treatment and while still infectious he rode in the presidential limousine past supporters who were camped outside Walter Reed Medical Center (maskless, of course) to give them a thrill and to bask in the waves of irrational adoration to which he was addicted. The adventure needlessly exposed Secret Service agents to Covid.

After having a photo op in the hospital showing himself pretending to sign a stack of blank pages, Trump was discharged. Immediately upon touching down on the White House lawn, he huffed and puffed up a flight of stairs, took off his mask with bravado, and saluted the cameras like Il Duce on a bunting-draped balcony. We wondered how many public servants inside the residence were endangered by his behavior. The Washington Post reported that 130 Secret Service agents were ultimately infected or quarantined in service to Trump's ego.

As America may have finally realized through Trump’s richly deserved illness that Covid-19 was serious and his approach to it unconscionable, the first Biden/Trump debate likely put an end to anyone’s notion that Donald’s personality was “direct and honest” instead of simply vulgar and mean. Spewing lies and poison--perhaps literally disease--he interrupted every response by the former Vice President and strutted like a schoolyard bully. Jake Tapper denounced the performance as a “train wreck,” and historian Jon Meacham declared the debasement of a seventy-year tradition of presidential discourse. Not only were wonky, newsroom elites sick to death of Trumpism, but regular folks like you and me agreed the country had had enough of Trump's rank vulgarity.

The difference between the elections of 2016 and 2020 is well-represented by what happened in my home state of Pennsylvania: more black voters turned out in urban Philadelphia to support Biden, and white suburban women, like the ones who marched in my neighborhood racial justice protest, abandoned Trump who had supported him four years before. Even so, five days passed between election night and when the Associated Press declared Joe Biden the victor, not so much because the vote was close--it wasn't that close--but because so many people voted by mail. Tasteless and destructive to the bitter end, Trump refused to accept the results, amplifying far-fetched conspiracy theories tweeted in Cloudcuckooland and heedless of the perhaps permanent damage he was doing to the credibility and sanctity of our election process. In a rare spasm of honesty, he had been telling the American people for months he would refuse to accept the outcome should he lose. Just as he had always managed to avoid financial consequences by outlasting the average creditor in courts of law, he pursued 60 different legal challenges to results in Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Georgia, and Arizona; most were lost and many were dismissed with the judges heaping derision on Trump's legal beagles. None of them changed the outcome of individual state elections. Even the Supreme Court he had hastily packed with one final appointee, less than a month after the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, refused to listen to his baseless arguments, construed to overturn the will of the American people without a shred of credible evidence of widespread fraud.

The difference between the elections of 2016 and 2020 is well-represented by what happened in my home state of Pennsylvania: more black voters turned out in urban Philadelphia to support Biden, and white suburban women, like the ones who marched in my neighborhood racial justice protest, abandoned Trump who had supported him four years before. Even so, five days passed between election night and when the Associated Press declared Joe Biden the victor, not so much because the vote was close--it wasn't that close--but because so many people voted by mail. Tasteless and destructive to the bitter end, Trump refused to accept the results, amplifying far-fetched conspiracy theories tweeted in Cloudcuckooland and heedless of the perhaps permanent damage he was doing to the credibility and sanctity of our election process. In a rare spasm of honesty, he had been telling the American people for months he would refuse to accept the outcome should he lose. Just as he had always managed to avoid financial consequences by outlasting the average creditor in courts of law, he pursued 60 different legal challenges to results in Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Georgia, and Arizona; most were lost and many were dismissed with the judges heaping derision on Trump's legal beagles. None of them changed the outcome of individual state elections. Even the Supreme Court he had hastily packed with one final appointee, less than a month after the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, refused to listen to his baseless arguments, construed to overturn the will of the American people without a shred of credible evidence of widespread fraud.

As I write these words, just hours before the end of the most stressful and heartbreaking year for my country through which I have ever lived, Trump is still disputing facts, fuming against his myriad enemies and betrayers, and still trying desperately to avert the inevitable transition of power twenty days hence. Credible news sources and specialists in Constitutional law assure me my anxiety is unfounded and Trump will leave the White House at noon on the appointed day, kicking and screaming if need be. My country is in chaos. Cases of Covid-19 are nearing 20,000,000 and deaths are at 344,000 with an 70% more contagious mutation of the virus gaining a foothold in the country, even as hospitals are crammed to near capacity with the sick and doomed. Yet, whatever we face in the coming year, we will not have to do it with Donald J. Trump in the lead role, and for that reason alone, I feel truly blessed.

As I write these words, just hours before the end of the most stressful and heartbreaking year for my country through which I have ever lived, Trump is still disputing facts, fuming against his myriad enemies and betrayers, and still trying desperately to avert the inevitable transition of power twenty days hence. Credible news sources and specialists in Constitutional law assure me my anxiety is unfounded and Trump will leave the White House at noon on the appointed day, kicking and screaming if need be. My country is in chaos. Cases of Covid-19 are nearing 20,000,000 and deaths are at 344,000 with an 70% more contagious mutation of the virus gaining a foothold in the country, even as hospitals are crammed to near capacity with the sick and doomed. Yet, whatever we face in the coming year, we will not have to do it with Donald J. Trump in the lead role, and for that reason alone, I feel truly blessed.

Art Too Bruté

(continued from first blog page)

A talk given in 1951 during a blinding, Chicago snowstorm enumerates Dubuffet’s deep suspicions about contemporary man’s faith in reason.

Western man believes that his mind is capable of acquiring a perfect knowledge of things. He is convinced that the rest of the world keeps perfect step with his reasoning faculties. He strongly believes that the principles of his reason and especially those of his logic are well founded. (Glimcher, 127)

Dubuffet skeptically dismisses ideas and language as being wholly useless to convey real experience, describing the former as “a lesser degree of the mental processes, a level on which the mental mechanisms are impoverished, a kind of outer crust formed by cooling” (Glimcher, 128) and criticizing language for its clumsy metaphors and awkward syntax that obscure instead of illuminating. No worthwhile art, Dubuffet lectures, originates from ideas or verbal descriptions, which are only the secondary markers of lived existence. Reality in the abridged, portable edition disinterests him.

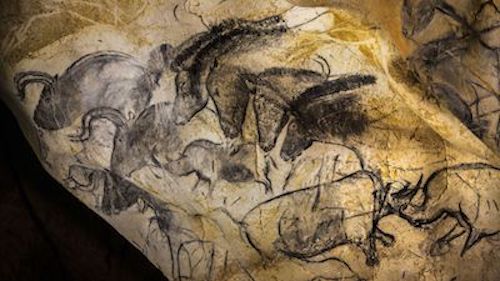

Unsurprisingly, Dubuffet champions human art that precedes written language at least by tens of thousands of years. Likely, the cave paintings of Chauvet and Lascaux even predate most spoken constructions of language. The artist speculated with his peers in Chicago, 70 years ago, about the influence of anthropological and art history assessments of “so-called primitive” painting and sculpture on a general trend to reevaluate the Occidental elevation of ideas and arguments over intuitive apprehension (Glimcher 127) . Werner Herzog’s 2010 documentary Cave of Forgotten Dreams makes it impossible to describe the art of Chauvet Cave as primitive in any regard. The film illustrates the sophistication of chroniclers of a time 50,000 years in the past, technically advanced in their abstraction of animal forms, expressive in their dramatization of movement and moment, resourceful in their utilization of available pigments and their incorporation of the contours of the cave walls in their depictions, and spiritually advanced in their understanding of the unity of man and nature. So a part of the world of gorges, forests, cave bears, lions, and rhinos were these early artists, they painted figures that combined the features of humans and animals, expressing their continuity. Dubuffet laments the Western elevation of reasoning over intuition and the divorce of civilized humanity from its animal identity.

makes it impossible to describe the art of Chauvet Cave as primitive in any regard. The film illustrates the sophistication of chroniclers of a time 50,000 years in the past, technically advanced in their abstraction of animal forms, expressive in their dramatization of movement and moment, resourceful in their utilization of available pigments and their incorporation of the contours of the cave walls in their depictions, and spiritually advanced in their understanding of the unity of man and nature. So a part of the world of gorges, forests, cave bears, lions, and rhinos were these early artists, they painted figures that combined the features of humans and animals, expressing their continuity. Dubuffet laments the Western elevation of reasoning over intuition and the divorce of civilized humanity from its animal identity.

We understand intuitively that language describes experience after the facts materialize; words don’t originate that which is real. Sartre divined his insight that being precedes essence and granted license to fellow Frenchman Dubuffet to discount the words we use to characterize the phenomena around us. That being stipulated, language and the artifacts it produces are not going to disappear. It can’t be observed or quantified, but the stream-of-consciousness narrating the life of every human must be inferred. Most of us are aware that our thoughts, fears, and obsessions have no true correspondence in the physical world, but apart from imposing chants, mantras, or pop culture slogans on the palimpsest of consciousness, who can turn off that running spigot for even ten seconds?

...

Samuel Beckett expresses his frustration with a reality conveyed by mere words in a 1937 letter to his friend Axel Kaun:

It is becoming more and more difficult, even senseless, for me to write an official English. And more and more my own language appears to me like a veil that must be torn apart in order to get at the things (or the Nothing-ness) behind it. Grammar and Style. To me they seem to have become as irrelevant as a Victorian bathing suit or the imperturbability of a true gentleman. A mask…Is there any reason why that terrible materiality of the word surface should not be capable of being dissolved? (Winkler)

Language exists indelibly in the environment outside and inside our heads. Beckett couldn’t exile consciousness, so he had to settle for the Nobel prize. That’s the thing about art: it’s futile, ridiculous, but it consoles.

Dubuffet’s advocacy for outsider art, or “Art Brut,” usefully expands awareness of the powerful expressions of the human condition that fall outside the narrow conventions of “cultural art”-- a board game, in which players trundle predefined tokens around an official path that rewards them with Monopoly money to calibrate the winners and losers.  Dispensing with the grid of language is Dubuffet’s own art, his l’Hourloupe people and fanciful, painted epoxy landscapes, springing up like mushrooms in public squares all over the world. He claimed he actually saw these forms, as William Blake told us he communed in person with anatomically correct angels, and Carlos Castaneda told us he saw the human form as a luminous, tentacled egg. More important than the assertion that Dubuffet’s work is free of the clumsy syntactic structures and metaphors of language is its realization of a uniquely individual view of what is real. We have an idiosyncratic system of ideas and metaphors in consciousness, hidden away from others struggling under the weight of their own delusions and fantasies, and as B.F. Skinner said, mentalisms mayn’t account for behavior or be empirically observable, but it sure would be interesting to get a glimpse of anyone’s inner life apart from our own.

Dispensing with the grid of language is Dubuffet’s own art, his l’Hourloupe people and fanciful, painted epoxy landscapes, springing up like mushrooms in public squares all over the world. He claimed he actually saw these forms, as William Blake told us he communed in person with anatomically correct angels, and Carlos Castaneda told us he saw the human form as a luminous, tentacled egg. More important than the assertion that Dubuffet’s work is free of the clumsy syntactic structures and metaphors of language is its realization of a uniquely individual view of what is real. We have an idiosyncratic system of ideas and metaphors in consciousness, hidden away from others struggling under the weight of their own delusions and fantasies, and as B.F. Skinner said, mentalisms mayn’t account for behavior or be empirically observable, but it sure would be interesting to get a glimpse of anyone’s inner life apart from our own.

In Dubuffet’s aesthetic, art should be valued for its freedom from false, logical constructs of reason and its nearness to man’s primal self, connected to nature, and yet, each of us carries within our organism a persistent landscape of memories, attractions, and aversions that only become more tangled and irreducible as life drags on. In a 2018 interview with Scientific American, Neuro-Philosopher Peter Carruthers proposed that the idea of conscious judgment and understanding is itself an illusion, that physical processes within the brain--perhaps simultaneously occurring within our entire body--are the seat of inferences, and our connections between reality and these purely physical processes remain unconscious, out of reach from the rambling voice in our head (Ayan) . Grappling with a premise in our internal dialogue is a reaction to an argument that has already been resolved elsewhere in our organism. Here’s the thing: isn’t it fair to say that a vast complex of hidden features and processes over which we can exert no influence and about which we have only second-hand understanding is much the same, in its mystery and dreadful aspect, as the external, natural world?

Art that pursues the unnameable aspects of individual character for the purpose of illumination and self-recognition disdains commercial or institutional success, yet these private revelations can be deeply moving to others. Especially, outsider art fascinates an audience with an appreciation for one of humanity’s great mysteries: Why do we compulsively cover the walls of our caves with vain mementos of our arbitrary exis-

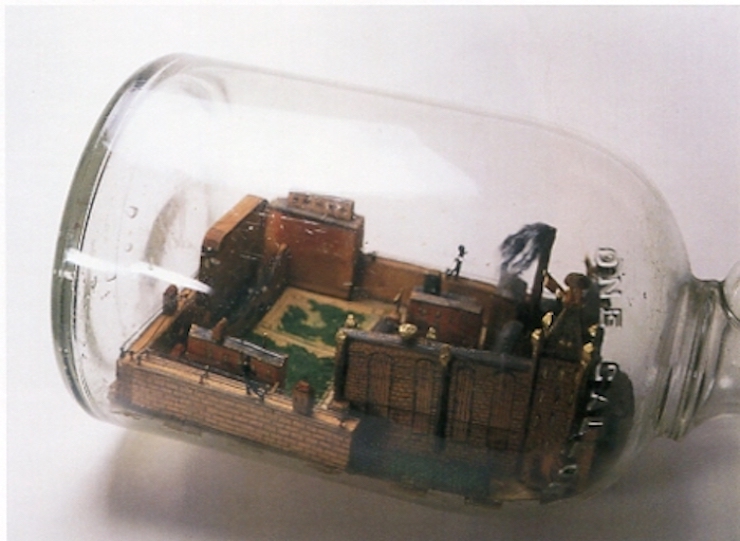

An anonymous artist represented the Maryland State Penitentiary with a prominent ballfield in this whimsy bottle from a show at the Museum of American Folk Art.

tence? Henry Darger is perhaps the most notorious, completely untrained artist whose impulse to record his eccentric relationship to society was undeterred by his wretched isolation from it. I saw selections of his collage and watercolor fantasies of the fulsome “Vivian Girls in the Realm of the Unreal” when they were exhibited in ABCD: A Collection of Art Brut at the Museum of American Folk Art in 2001. Discovered after his death in a vast cache of 15,000 written pages and 300 illustrations, Darger’s work was shelved in the boarding house where he lived and worked and chronicles the fantastic, often violent, adventures of seven princesses of the Christian land of Abbieannia. The torture, suffocation, and imprisonment of these amorphously sexual little girls was a recurring motif in Darger’s sweetly deranged narrative. Clearly the reclusive artist and novelist was making concrete something deeply personal and probably deeply painful with his epic arrangements of cherubic female (and often hermaphroditic) children, whose appearance recalled paper cut-out dolls from Victorian-era nursery books.

Research and speculation about the life of Darger churns up the kinds of horrific details we are used to uncovering as a prelude or explanation to lurid crimes, not to a life of quiet, artistic exertion. His work has the scintillating allure of documentary evidence from a deluxe edition of Psychopathia Sexualis. Orphaned, abused, and sent to a state-run asylum for feeble-minded children, Darger eventually made his way to Chicago, where he worked for decades as a janitor in a Catholic hospital. Although the squalor of his childhood, long years of drudgery as an unskilled laborer, and social isolation make a dramatic background to the revelation of Darger’s monumental trove of creations, making one-to-one correspondences between those biographical details and his bizarre, almost certainly creepy catalog ignores the ultimately unanswerable question of why he was motivated to ceremoniously express the dark shadows of his inner life.

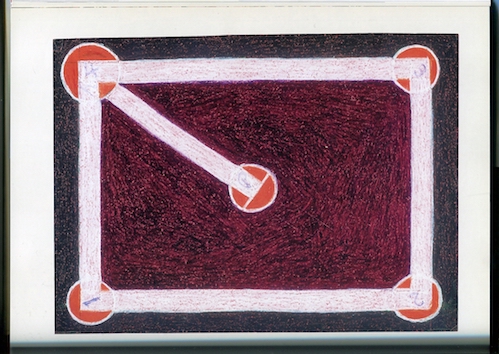

Undoubtedly, it isn’t Darger’s luridly febrile, fantasy enactment of his bleak personal history that audiences relate to, but the inexplicable courage motivating his expression of it. The catalogs of other outsider artists are far less baroque, yet still possess the dauntless passion to illustrate their psychic drama. In the American Museum of Folk Art’s Baseball exhibition, the work of psychiatric patient Eddie Arning, representing with a child’s crayon colors, slathered on paper, the familiar diamond of the infield, possesses a remarkably abstract minimalism. Arning reduces the various pleasures of boyhood encounters with an empty-lot pastime to a geometric simplicity, using the most available materials. The Reverend James Hampton, whose religious

visions fill a gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, spent decades amassing his Throne of the Third Heaven using silver and gold foil, cardboard, and tape. An inmate in the Baseball show placed in bottles wood slivers coated with model paints and made at least one museum-goer cry. Darger appropriated coloring books to express his alternate world of ambiguously sexual nymphs, and his resourcefulness connects him to Arning and the others as surely as the contrasting representation of details in their work distinguishes them.

visions fill a gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, spent decades amassing his Throne of the Third Heaven using silver and gold foil, cardboard, and tape. An inmate in the Baseball show placed in bottles wood slivers coated with model paints and made at least one museum-goer cry. Darger appropriated coloring books to express his alternate world of ambiguously sexual nymphs, and his resourcefulness connects him to Arning and the others as surely as the contrasting representation of details in their work distinguishes them.

Neither mental illness or a lack of sophistication identify the masters of Art Brut. Dubuffet requires its practitioners to operate outside of the official, confining space of the academy and the world of commercial galleries, but “self-taught” isn’t synonymous with bumpkinhood. Autodidact has a more appropriate connotation to describe the maker of Thornton Dial’s tin-plate and driftwood marvels, or the earnestly simple, social commentary of Horace Pippin. As for the mentally unbalanced, Dubuffet remarks that “the mechanisms of artistic creation are exactly the same in their hands as in those of any supposedly normal person.” (Gilcher, 104) Importantly, formal reasoning isn’t a requirement for creating artistic expressions of the human condition. “Clairvoyance” is the qualifying characteristic of those who take the dingy commonplaces of their personal history and discover the means--however unsophisticated--to communicate them vibrantly to the world.  Whether we are talking about the prosaic scarves and hats of a Grandma Moses sledding hill or the pitched, feverish battles of Darger’s doll brigade with a godless cadre of sadistic Sourdoughs, insight divines the universal and recognizable attributes in the most extreme personal experience.

Whether we are talking about the prosaic scarves and hats of a Grandma Moses sledding hill or the pitched, feverish battles of Darger’s doll brigade with a godless cadre of sadistic Sourdoughs, insight divines the universal and recognizable attributes in the most extreme personal experience.

The recognition of the hand of the artist, I believe, is the paramount qualifying attribute of what we colloquially refer to as art. If I understand Dr. Carruthers correctly, judgments, perceptions, and the seeds of what will become obsessions accumulate in our bones, as it were, and an individual has no conscious access to these processes. That part of us which resides in the recording present relates with the same uncertainty or awe to that buried self as if it were implacable Nature herself. The artists in the limestone caves of France exerted a measure of control over a harsh environment, filled with predators and pitfalls, by mastering its forms within and upon the relatively civilized recesses of a canyon wall. Through a process we cannot perceive or truly comprehend, some persons are fated to slash their graffiti on the walls for the rest of us. The ultimate testament to their skill and technique is that we recognize the human qualities of their gestures across the chasm of tens of thousands of years, and across the divide between the sane and insane.

--October, 2020

Ayan, Steve, “There Is No Such Thing as Conscious Thought,” Scientific American, Springer Nature,

12/20/2018, www.scientificamerican.com/article/there-is-no-such-thing-as-conscious-thought/,

10/23/2020.

Borum, Jenifer P, ABCD: A Collection of Art Brut, 2001, Museum of American Folk Art, New York.

Gilcher, Marc, ed., Jean Dubuffet: Towards an Alternate Reality, Pace Publications, Inc.,New York, 1987.

Gôméz, Edward M., “The Sexual Ambiguity of Darger’s Vivien Girls,” Hyperallergic, Hyperallergic Media,

06/24/2017, https://hyperallergic.com/387178/the-sexual-ambiguity-of-henry-dargers-vivian-girls/,

10/23/2020.

Warren, Elizabeth V., The Perfect Game: America Looks at Baseball, American Folk Art Museum/Harry N.

Abrams, Inc., New York, 2003.

Winkler, Elizabeth, “Beckett’s Bilingual Oeuvre: Style, Sin, and the Psychology of Literary Influence,”

The Millions, Seth Dellon, www.themillions.com/2014/08/becketts-bilingual-oeuvre-style-sin-and-the-

psychology-of-literary-influence.html ,10/23/2020.

A walking tour of City Hall-area sculpture

(continued from first blog page)

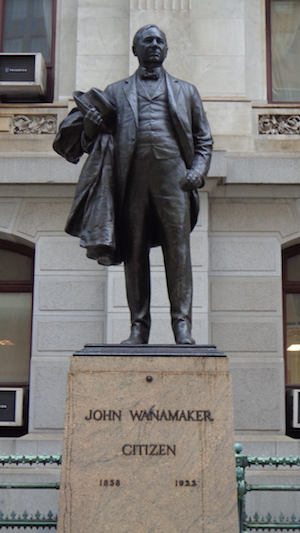

A representation of the most prominent member of the Philadelphia merchant class extends the City Hall theme of civic responsibility, especially by those who have most benefited from Philadelphia's cultural infrastructure, its government, schools and universities, hospitals, philanthropic institutions, and industrious working class. Wanamaker lived in a city with a rising consumer class that he induced to shop at his modern "department store" with innovations such as a money-back guarantee and fixed pricing. He was a pioneer in the use of advertising who enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship with the local newspapers: they had the readership and he had the advertising dollars. Wanamaker paid for the first ever half-page advertisement, and later became the first to buy a full pager.

its government, schools and universities, hospitals, philanthropic institutions, and industrious working class. Wanamaker lived in a city with a rising consumer class that he induced to shop at his modern "department store" with innovations such as a money-back guarantee and fixed pricing. He was a pioneer in the use of advertising who enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship with the local newspapers: they had the readership and he had the advertising dollars. Wanamaker paid for the first ever half-page advertisement, and later became the first to buy a full pager.

John Wanamaker's civic-mindedness may have contributed to his desire to become a US postmaster general (the papers said he bought the appointment from President Benjamin Harrison), where he innovated the first commemorative stamp. He contributed to many cultural and philanthropic causes, including founding the Sunday Breakfast Rescue Mission and financing a campaign to make Mother's Day a recognized holiday. Famous for promoting thrift, Wanamaker inspired school children all over his city to collect $50,000 in pennies towards the creation of his statue after his death.

Scottish sculptor John Massey Rhind was a leading creator of portrait statuary at the beginning of the twentieth century, whose dozens of historical subjects are found across the country, including in the National Statuary Hall Collection in the Capitol. In Philadelphia, he created the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Memorial on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway and the Lenape Warrior placed by the Wissahickon Creek. Rhind supervised Alexander Milne Calder's apprenticeship in sculpting back in Scotland.

Turning the corner from the statue of Citizen Wanamaker, the walking tour crosses JFK Boulevard to attain One Broad Street, the site of the Masonic Temple, home of The Right Worshipful Grand Lodge of the Most Ancient and Honorable Fraternity of Free and Accepted Masons of Pennsylvania. Is the conspicuous placement, on prime real estate directly across from City Hall, of the Western world's most notorious secret society, a diabolical challenge to secular law or the benign establishment of a cozy clubhouse for the brothers downtown? (See my related post on Freemason mysticism.) The temple façade, designed by architects William Rush and James Windrim, hints at the answer.

Visitors to the Grand Lodge pass through a series of nested arches marked with abstract designs. In contrast, we have seen how the generically named City Hall decorates an archway with quite literal lions and bulls. Restraining the figurative representation of any part of God's creation invokes Eastern religion, which is just so well misunderstood here in Philadelphia that it may as well be some really cool hocus pocus to scare the bejeezus out of guys. Additionally, the series of arches relates to the initiation of the Freemasons and their elaborate hierarchy of "accepted" members. While City Hall embodies the principle that all men are free and equal partners in civic government, the Masonic Temple represents a strict social hierarchy where the merits of individuals are carefully weighed and those who are lacking may not enter. We are told that the Grand Poobah of the Philadelphia Lodge made John Wanamaker a high ranking Brother "on sight." The statue of the man is right across the street, evidence of what could be perceived about him from mere appearance: mainly, he was white, male, and wealthy.

The tour is not alone. We share the sidewalk with a pair of very conspicuous Freemasons, represented in bronze and meeting "on the square," as it were. We recognize them instantly from their portraits on our money: it's Ben Franklin, Grand Master of the Pennsylvania Lodge, and Brother George Washington of the Alexandria, Virginia, Freemasons. The statue ensemble, created by realist sculptor James West, illustrates Washington presenting his sacred credentials, a Masonic Apron, to the Philadelphia Grand Master, who is already wearing his, and Franklin makes a welcoming gesture towards the Temple entrance. West named the sculpture The Bond. Here, near the epicenter of Philadelphia government, a scene that runs contrapuntally to the egalitarian conception of Democracy in America. Two of the Founding Fathers (there's none more foundery) demonstrate that a secretive all-male club exists beneath the protocols of public governance, and this network will judge the usefulness of individuals to the group, it will cultivate its own causes, and it will have its own bonds and its own influence. G!

This near to City Hall, we've seen several sculptures in a realistic style, used to describe a historical subject and in that way commemorate it for the edification of the public. Marching up Broad Street like the Mummers themselves, we're going to avoid for a while longer the antithesis of realism—abstraction—and consider instead a fine example of a precise rendering of objective form that is nevertheless employed abstractly. The strictly metaphorical use of everyday objects is the bailiwick of Pop artist Claes Oldenburg, whose ginormous Paint Torch is across Broad on Lenfest Plaza, next to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

As one of several institutions that has an influence on public sculpture in Philadelphia, PAFA endorses work whose subject is the multitude of ways we understand existence, veering away by a couple of blocks from the civic-minded purposes of the great men posed on and around City Hall. In a city with a profound respect for the cultural and financial benefits of its stellar educational and artistic academies, PAFA gives expression to Oldenburg's satirical gesture without sacrificing the hoary respectability of the school that trained Thomas Eakins and made him the head of their painting department. Paint Torch ironically presents a monumental artist's brush loaded with glossy, orange pigment, and that's a fairly good emblem for the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts next door. By scaling up an ordinary tool to enormous size, the artist demands our tour realizes that, while the formal content of the paint brush remains, its utilitarian object is no more. What is left is an angled erection flicking an iridescent glob, a stark, nudge nudge metaphor for the act of creation.

Staying on this side of Broad Street, let's walk back towards City Hall, across Vine Street, and go up the stairs on our right towards the dominoes, Chess pieces, and Monopoly tokens in the Board Game Art Park. Next to the Municipal Services Building are playing pieces representing a pitched battle that unfolded in the 70s for control of public art in Philadelphia. On the one side, represented by the nine-foot bronze statue of former Mayor Frank Rizzo, stand advocates for the view of the common taxpayer (whatever that is) who want easily recognizable likenesses without a bunch of artsy mumbo jumbo they don't understand. On the other side, represented by Jacques Lipchitz's Government of the People, the Fairmont Park Art Association (now, the Association for Public Art) takes a wider perspective: our public art should embody the highest ideals and historical trends of art worldwide, befitting a world-class city.

Commissioned by the city of Philadelphia, the great Cubist sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, then living in New York, had produced a plaster model for the 200th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Two of his sculptures were already in public spaces in the city, Prometheus Strangling the Vulture on the steps of the Philadelphia Art Museum, and Spirit of Enterprise along Kelly Drive in the Samuel Memorial Sculpture Garden. Not immediately accessible cognitively to those who are unfamiliar with the Cubist style are the works' abstraction of human and animal forms and their reckoning with the puzzle that is human visual perception, the problem of representing in a static medium living objects that exist in 360 degrees and from moment to moment. Before Lipchitz's third monument could be cast in bronze, Mayor Rizzo put the kibosh on the project, decrying its model as looking like "plasterers had dropped a load of plaster" and refusing to spend another dollar of taxpayer money on such folly.

Flexing a muscular apparatus operating outside City Hall, namely philanthropic investors in culture and other art people, the Fairmont Park Commission raised $350,000 to complete the casting of the 33-foot sculpture in bronze. By means of this clever stratagem, objections that the average citizen wouldn't understand the work were neutralized. "If they didn't pay for it, they don't have to look at it." Of course, in the ensuing decades, Lipchitz's pyramidal form showing generations of men and women supporting each other to achieve a vibrant government has come to be an accepted and even cherished part of the downtown scene. In a radio broadcast, even Mayor Rizzo admitted that his chauffeur was a fan of Government of the People. "That's what's great about this town. It has something for everybody!" Art critics called Lipchitz's last major sculpture a magnificent capstone to a career that was unceasingly idealistic and endorsed the struggle for freedom and self-realization.

Like other commemorative statues of great men, the realistic style of the Frank L. Rizzo Monument encourages appreciation of the breadth of the subject's life in addition to the straightforward reportage of his dimensions. At nine-foot, the statue's height is admittedly larger than life. Ironically, seeing more than the surface contains is the vantage from which some of the most visually complex or provocative works of the Modern canon are understood, works by Duchamp down the Parkway in the Philadelphia Art Museum, for instance. The mayor's life was the topic when a private organization raised the funds for the statue and petitioned to symbolically place it across from City Hall in proximity to the Lipchitz masterpiece the mayor once derided. His son, councilman Frank L. Rizzo, Jr., softened objections to the close pairing by allowing that his father's opinion of Government of the People had softened over the years.

Unfortunately for sculptor Zenos Frudakis' evocative Rizzo monument, affection for the legend of the late mayor has dimmed, and the legend comprises the largest part of what recommended the bronze behemoth to the public in the first place. No longer thrilling is the story of Hizzoner leaving a formal banquet in a tuxedo to wade into a brewing riot with his nightstick tucked into his cummerbund or breaking his hip when, policing a South Philadelphia refinery explosion, he was run over by a fire truck. The mayor's bluster and populist demagoguery are viewed as divisive of the community, not representative of it. In 2017, current Mayor Kenny stated that, like statues of Confederate generals in the South, it was time for Frank Rizzo to give ground. Maybe it would have been less a target of revision had the bronze portrait been made of paper mâché and tucked away in a less obvious corner on the inside of City Hall, as in the mid-'Aughts was my own The Mayor of Heaven, a Mummery.

Let us move away for the time being from the controversial give and take between popular sentiment and educated art opinion, or private and civic interests. On the 15th Street side of the Municipal Services Building may be found George Greenamyer's lighthearted Philly Firsts. The wire, tin plate, and colorfully painted assemblage uncontroversially illustrates local history-making events such as the performance of the first circus, Frank Furness' design for the PAFA building, the first fire brigade, and Betsy Ross' stitching of the first national flag. Greenamyer's bright colors, informal materials, and folksy renditions distinguish the piece from any of the traditional bronze monuments we've seen to this point, and although it has the humor and pigmentation of Oldenburg's paint brush, it lacks the ironic sensibility. A look at other examples of installations by the American sculptor and Philadelphia College of Art graduate confirm his almost folklike innocence of historical controversy and indifference to technical sophistication. A city-appointed committee chose Philly First over other responders to an open call for artists.

By some measures the most renowned sculpture on our walking tour, Robert Indiana's Love Statue may be viewed in Love Park (JFK Plaza) from 15th Street at the top of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. The work commands the glorious vista from Billy Penn's tower clear down to the Art Museum. Though especially fitting for our City of Brotherly Love, Indiana's iconic four-part stack of serif font lettering appears in practically the same form all over the world, including Manhattan, Switzerland, across town on the University of Pennsylvania campus, in Washington, D.C., Israel, and Indiana. Note that it uses industrial materials and bright colors as does the Greenamyer work we visited, but the perfection of the graphics is much more sophisticated and contributes to its universal appeal.

On his web site, the late sculptor describes the viability and pertinence of simple words and their lettering as a subject for art, a practice that originates in early 20th century collage works and paintings of Kurt Schwitters, Picasso, Leger, and others, through the Pop era, including Lichtenstein, Warhol, Rosenquist, and Jasper Johns. The artist elucidates the circular form of his composition, the clockwise flow of the letters, and the reference to the circular in the "o" made conspicuous by its tilting. Jasper Johns has said certain forms like flags, targets, maps, and trademarked logos are so ubiquitous we don't even perceive them as representations; they are forms excluded of content, pure abstraction. Whether Robert Indiana intends this work as a benediction for visitors to Philadelphia or a graphic design stripped bare of meaning makes a worthwhile question to ponder as we cross two streets and proceed to 16th and the Parkway.

Near an upscale cafe stands a reddish stone monolith so modest in its achievement one is tempted to think it's the cafe's mascot, like the mermaid for Starbuck's, and not a sculpture along a route with many international masterworks. Jacob Lipkin's The Prophet appears half-formed, as if the sculptor was attempting to convey Michelangelo's trope of showing pure form erupting from unhewn marble. Instead, this patriarch looks indefinite and undetermined, tentatively pulling on his beard and wondering what to say next. "Tuesday would be a good day to let someone else buy you a cappuccino." In fairness, other stone and wood products by the artist eschew detail, intending to convey the relatedness between man and Nature by, goshdarn, not removing enough of the latter to fully describe the former. The Prophet weighs a remarkable 9000 pounds and ended up an outside sculpture because it wouldn't fit conveniently on the inside. If it wore a delineated garb, bore articulated limbs and fingers, and a wrinkle-creased brow, the rubble on the studio floor could have subtracted a full ton from its bulk, making it more exhibition ready.

Our tour could have walked right past this sculpture on the way to some truly remarkable works less than half a block away, but in its semi-forlorn simplicity it has the needy appearance of one of Al Capp's lovable shmoos, the happy friend of man that offers itself up for easy eatings, or the old man who's a regular subsidiary character on The Simpsons. In earnest, let us acknowledge that the graphic simplicity of the Love statue offers that piece a presence and authority, which is a much different result than appearing only partially conceived. Our walking tour contrives to weave several themes marching from station to station, but it is worth being reminded of the fact that the placement of each has an element of randomness, defying meaning and an overarching design.

Heading towards 17th Street, we find Henry Moore's remarkable emerald form, weathered bronze on a black granite base, his Three Way Piece Number 1: Points, purchased and placed by the Fairmont Park Commission (now aPA) soon after it was cast in 1964. Moore stated that the best of his sculptures were made for the outdoors, and in so far as this one rests on a thin strip of lawn, we can appreciate it in a complimentary situation. Natural forms such as stones, pebbles, weathered wood, bones, and ancient landscapes are the inspiration for the major English sculptor of the last century. His studio featured an elephant skull which contained natural passageways that enabled one to look through the massive fossil, concavities that also occur in surf-worn shells or caves along a seaside cliff. The frequent appearance of such holes in Moore's work relate to these natural models and help to integrate his sculpture with the surrounding landscape. Essentially, Moore's art reflects natural processes and Nature's compositions.

The title of Moore's work informs us it's abstract, and that, like Government of the People, it unfolds to the eye differently depending upon from which angle a viewer regards it. Three Way Piece doesn't possess a front and a back. Although it isn't representative of a specific subject, it does carry a signature quirk of Moore's sculptures: a large mass held up by a tiny leg, evocative of the singular anatomy of birds and the birdwatching pastime that is a favorite in the English countryside where Moore spent his childhood and had his studio. On our tour, we've said enough about the deficits of the neighboring Prophet, but let us appreciate Moore's mastery in comparison to the earlier sculptor at abstracting the particulars of actual living creatures. He suppresses singular details while revealing the underlying form. Moore stated that the best schooling he received as an artist was examining the history of art in the British Museum, where he was deeply affected by the sculpture of ancient civilizations that generalized the characteristics of the human body rather than realistically and exactingly representing them.

Just a few paces down the Parkway brings us to the intersecting steel plates of Three Discs, One Lacking, an abstract by Philadelphia's favorite son, Alexander Calder. His grandfather was responsible for the William Penn statue and other decorations on City Hall; his father, Alexander Stirling Calder, produced the splendidly lush Swann Memorial Fountain, in Logan Circle on the Parkway, and the powerful Shakespeare Memorial a few blocks away, in front of the main branch of the Philadelphia Free Library. A three-generation dynasty of sculptors of public art perhaps speaks to the nature of influence and the importance of a strong network of connections to building a sustainable art career, although this is not to diminish in any way the genius of the remarkable Calders. The grandfather and father of Sandy Calder, as he is known, both studied under Thomas Eakins at PAFA, and the imprimatur of that esteemed local institution played a part in establishing their preeminence.

Constellations, mountains, geometry, and gravity itself inspire Calders abstractions, but his workmanlike skill with metal and playful exploration of what the materials are capable generate his familiar mobiles (a name given them by Marcel Duchamp) and stabiles (so dubbed by Jean Arp). Anyone who has ever struggled with steel wire has only to see the tight coils, precise crimping, and accuracy of Calder's wire portraits to appreciate his mastery with metal.

Calder studied in Paris as a young man, and he initially built a reputation for creative ingenuity with his suitcases full of circus puppets, from which he would regularly perform. Film of his circus recital curated by the Whitney Museum reveals the artist's undeniable personal charm and indelible sense of humor, and these qualities imbue his sculpture. Philadelphia is the home of Calder's largest mobile, in the Federal Reserve Bank on 6th street and accessible after an airport-style security check. From the Great Hall of the Philadelphia Art Museum, Alexander's mobile Ghost, his father's Four Rivers Fountain, and his grandfather's statue of Penn are simultaneously visible.

Letting Calder's discs, absent and otherwise, point the way to 17th Street, we encounter Barbara Hepworth's Rock Form (Porthcurno), a bronze from 1964. A friend and rival of Henry Moore, Hepworth lived and worked since the start of WWII in the Cornwall countryside, and like Moore, her sculpture is inspired by natural forms. Porthcurno is the name of a site near her home displaying rock stelae carved by the sea. Hepworth's sculptural innovation was carving out the interior of massive wooden logs to effect an embracing presence; instead of her sculpture being about an object in the landscape, space becomes the subject, and for Hepworth, the surrounding presence of a landscape may be felt by fully experiencing one of her towers or horizontal compositions.

Donated by art patron David Pincus to the Association for Public Art in 2011 and installed the following year, Rock Form (Porthcurno) is cast in bronze, the ancient preference for monumental sculpture but not the material in which Hepworth developed her unique vision. Like Moore, she had an affinity and aptitude for carving, especially in wood. Carving and chiseling are much different processes than modeling in clay and making a plaster cast to be developed at a foundry as a bronze final product. Subtraction describes the work of a chisel, while addition is the nature of sculpting in clay. For artists who were keenly interested in the interior of objects, to integrate them into and evoke a landscape, the steady reduction of material is organic to the finished effect. Like a prehistoric native hollowing out a canoe, Hepworth first worked with huge trunks of trees to form her curvilinear interiors that surround the viewer's searching gaze. Conscious of her worldwide reputation and having a mind to create from a global perspective, Hepworth began to work in weatherproof bronze because its products more sturdily survived transportation across long distances and could be placed directly in the landscapes that inspired their creator.

As we approach the final leg of our walking tour of Center City public statuary, let's turn south on 17th Street to just below Market Street, where we will find Roy Lichtenstein's wry, monumental Brushstroke Group on the righthand side. Fabricated of half-inch aluminum coated with pigment used to paint airplanes, the work is in Philadelphia through the efforts of The Association for Public Art, the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, and Duane Morris LLP, one of the city's prominent law firms and the owner of the adjacent building. It has been tucked away in its fairly obscure location since 2005, and peculiarly is on loan from the Foundation, meaning these brushstrokes could be erased at any moment! You will notice the unkempt grassy knoll, which is likely difficult to maintain owing to the presence of the statues and the ground-level lighting. Volunteers with heavy shears are welcome.

Lichtenstein (1927-1997), along with Warhol, Oldenburg, Indiana, Rauschenberg et al, is a preeminence of art's Pop heyday in the 50s and 60s, but the appearance of these brushstroke monuments all over the planet, including the Mediterranean harbor of Barcelona, establish his relevance to the modern discourse about the nature of Art. Pop most importantly turned on its head the idea that High Culture was the appropriate source for the themes and images in serious art, and its proponents incorporated movie stars, advertisements, and mass-market printing processes into their canvases and assemblages. Lichtenstein's series of paintings faithfully appropriating panels from romance comics are establishment icons, today. Besides its use of industrial materials, pop culture imagery, and its diminishment of the importance of classical painterly technique, Lichtenstein's work is an antithesis to the Abstract Expressionism that first located American artists in the forefront of worldwide art consciousness

Abstract Expressionism, having its own ax to grind with its predecessors, insisted that painting should eschew material subjects (landscape or portraits, for instance), and that the proper subject of painting was painting itself. The hand of the artist and her visceral gestures on the canvas, even the materiality of paint, became the essence of their big pictures. What Lichtenstein's work satirizes is the idea of painting about painting. Here, he has idealized the brushstroke using industrial materials and manufacture, creating a monument to painting itself that is literally called Brushstrokes, but doesn't contain a single remnant of the handmade painting process. The ironic subject of these playful constructions revises once again our concept of what art should be; a comical relativism towards ideologies and a disdain for every establishment restriction on what the artist should do is Lichtenstein's treasured legacy.

Are we there, yet? Getting weary and foot-worn? Take a few more paces and you'll enter from Ranstead Street Collins Park, whose formal address is 1707 Chestnut Street. Sit. Admire the garden planted with native Pennsylvania flora. Especially, absorb the beautiful wrought iron gate by sculptor Christopher Ray at the southern entrance. The park was dedicated in 1979. A private foundation turned over its maintenance to the Center City District Foundation, a downtown charitable institution, and the park's upkeep is funded by grants from The William Penn Foundation. Made in a style that is part Art Nouveau (the exacting execution of floral themes in an elaborately conceived design) and Surrealism (among the crickets, mantises, and birds is a nine-inch human figure in the upper corner), the fine gate of Collins Park reminds us that civic art is an amenity: it offers the intellectual comfort of challenging notions and remembrance of society's revered touchstones, and occasionally, physical comfort as well. Often it reflects commonly held values, but, as we have seen, a conflict exists between the lofty culture of artistic institutions and the presumed practical views of the public taxpayers. In this location, made possible by private and public players in the community, the pedestrian gets full sway.