David Lynch at PAFA: Why a Duck?

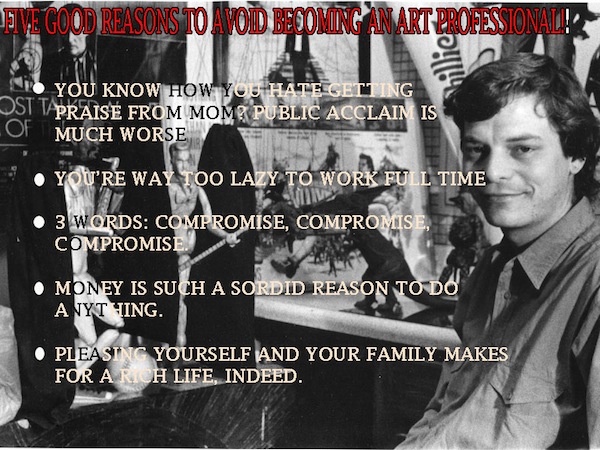

Julien Robson, who once judged me into a group show at the Main Line Art Center, mentioned in his talk about curating the show that the most useful distinction between a serious artist and a flower-pot painting amateur is that your professionals hold themselves accountable to the whole history of art. I love that statement for at least two reasons: one, it excludes everyone while naming a concrete and all-encompassing goal to shoot for, and two, it ignores technique, or suffering, or a degree from a respected institute and a testimonial from the Wizard of Oz as relevant qualifiers for the coveted title.

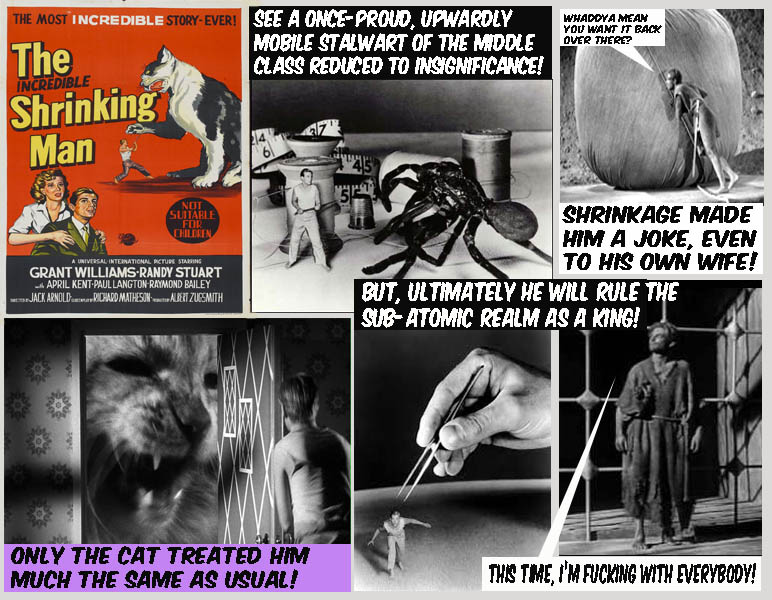

Mr. Lynch’s films and art works are nothing if not enigmatic. Most of modern art has an opacity about it, that sickening I don’t-have-enough-information feeling taking hold in a viewer, but a movie that doesn’t fall all over itself trying to declare what it means is rare, and Mr. Lynch has made several of those. The best thing about Lynch’s work is that meaning remains unclear and unresolved. The mechanism for wresting a moral from the story is present. We see it in the hard-working and straight-shooting detectives in Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks, but the plots amble towards an eventual revelation that doesn’t literally reveal anything, or at least anything useful to the human sensibility. Of Eraserhead, Lynch said it was “a Philadelphia of the mind.” A baffling movie becomes that much clearer: like Philadelphia, Eraserhead is about the decline of the Industrial Age, the stubborn and inconvenient fleshiness of the human form, and the importance of good grooming.

The point is to thwart revelation in a Hollywood-type vehicle that insists on disclosure. Lynch the movie-maker explains that, as much as we arm ourselves with facts and measurements, we don’t understand what’s going on, and even the most banal scenes and locations are fraught with cosmos-sized perils. Twin Peaks stripped away layer after layer of an insidious evil infecting a whole town, and called it "Bob." Bob turns up in the PAFA exhibit. Despite the promise in its title, Unified Field doesn’t tell us why things are the way they are either. The title of the collection refers to a branch of physics that attempts to discover the Theory of Everything, a single background of sums and data that unifies the four atomic forces: gravity, strong interaction, weak interaction, and electromagnetism. Every attempt at this is a failure: even at the level of pure math and science we can’t make all the numbers work out. String theory as an explanation has yet to be discredited, but it presumes an order of randomness and multiplicity that’s anathema to a unified anything.

A vanity is the belief that the human mind can grasp what the universe means. One should still take a scientific approach, but be content that science can’t explain nature in ways that will appeal to the human reason. Lynch on art said, “You can learn a lot by studying a duck.” The point there is that the composition of duckness is unsatisfying, all lopsided and cartoonish, but since the duck is a form created by nature, we should be content that it is perfect (eight billion years of evolution can’t be wrong). Lynch’s work explores a margin of aesthetics and observation where paradoxically the human desire for closure and balance are thwarted and our discomfort with randomness is ignored; nevertheless, “It’s art!”

David Lynch has made it clear over time that Philadelphia crystallized his understanding of art and the path he should take as an artist. A particularly intense night in the studio revealed to him the idea of a painting that moves. From this he made one of his finest pieces, the installation Six Men Getting Sick (1967). A projector plays a movie made with a crude camera over plaster casts of the artist wearing various expressions in various states of fulfillment. A siren screams continuously. The installation graphically depicts vomit passing through the six men as if they were culverts conducting life’s rejected dross, the horrific and ugly experience of a consciousness riveted to nature by illness, a doubter praying. Lynch might be using nausea as Sartre employed it, to describe the epiphany of realizing our utter aloneness and lack of resources, but in any case, human life is a sickness that only death cures.

Embrace the sickness. Philadelphia’s seedy, grimy, gray patina over scenes of depravity and loopiness heightened the state of emergency the artist David Lynch craved. PAFA’s notes tell us he was simultaneously horrified and energized by life in my city. He grew up in a picture perfect suburb in Montana but developed a grim, Gahan Wilson-like consciousness about the evil under the rose bushes. I love the opening of Blue Velvet, Jeffrey Beaumont’s dad in a Hugh Beaumont/Leave it to Beaver

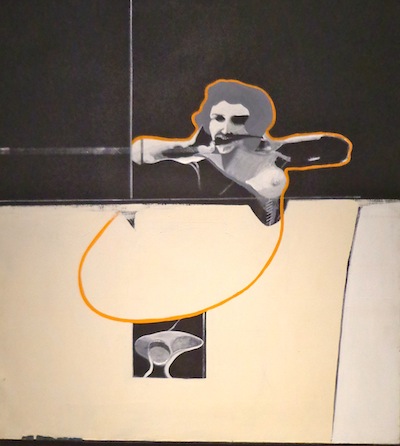

While David Lynch was at PAFA the MoMA had its huge Francis Bacon retrospective, and a couple of the works here crib from Bacon explicitly. They have the same museum or operating theater setting and vivisectioned subjects. I spotted the open mouth and pearly white signature of England’s superb and morbid portraitist, whose stated goal was doing for dentition what Monet did for haystacks. Francis Bacon’s visceral portraits of dissected humankind undoubtedly encouraged Lynch’s oddness and maybe the notoriously self-taught artist who mastered technique—but only so much technique as he needed-- gave Lynch the confidence to “loady up the truck and move to Beverly. Hills that is.”

Lynch’s very large works constructed on huge spans of cardboard with hard-wired lighting and all the other flotsam that makes its way into mixed media, commercial paint and industrial materials, signal an outsider sensibility, in this case, a creepy one. I think about the art work of marginal people, who don’t know about art, Windsor and Newton art, but know what they like, and what they want, and they make it themselves: shrines, mementos, and homunculi that reference the most banal private acts of perverse cruelty imaginable. I'm thinking about Ed Gein's lady shirt and Jeffrey Daumer's throne of skulls. Several of the works here use unwrapped cigarette filters to represent the intrusion of a death-obsessed corporate culture living in the dilapidated tract homes of the consumer-forging 50s. Lynch communicates in his films the unthinkable boogeyman lurking by the dumpster, behind the diner, or cruising through the neighborhood, driving too slowly.

Bacon’s Painting (1955) demonstrated the extreme viciousness and carnality of ordinary men. He does it with a confident brush, an umbrella, white teeth shiny with saliva, and a flayed carcass. The image is indelible and had its movie moment in Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs. That another fine American filmmaker was influenced by Bacon is something to ponder in the rich and disturbing PAFA show of David Lynch’s works, mounted on cardboard and presaging the most disturbing images in his big screen catalog: Laura Palmer’s blue cadaver wrapped in industrial plastic and left in the park and naked Dorothy Vallens running across the front lawn in Blue Velvet, interrupting her lover’s introduction of the girl next door to his horrified mom.

Click on this link to return to Top of Page or Table of Contents.

Jim Strong's "Transcribing the Wilderness"

“Working on mysteries without any clues..” –Bob Seger

“Something is happening, but you don’t know what it is.” –Bob Dylan

Jim Strong’s March 2023 show at Vox Populi Gallery dashes to the curb the vain, human hope of penetrating the mysteries of our existence. The accompanying statement for the installation tells us what to expect beforehand:

Transcribing a Wilderness is a practice of listening in tongues, combing everyday streams of information for hidden manifestos in misremembered bits of conversation, typos, scrambled notes, fragments of paranoid dreams and hallucinations.

The description of the show lists notoriously ambiguous or meaningless bits of evidence, but in fact, every human utterance is merely metaphorical, and even the most eloquent expression never gets us closer to whatever the hell the subject is.  Socrates said it, though it took him twenty or so conversations to finally blurt it out: “I know nothing, but at least I know that.”

Socrates said it, though it took him twenty or so conversations to finally blurt it out: “I know nothing, but at least I know that.”

Language is a hopelessly clumsy means to make sense of man’s earthly predicament, but so is every other symbolic language. “Abstract Art” is redundant. An image on canvas or sculpted in marble is no more what it intends to describe than “a summer’s day” adequately conveys the object of Shakespeare’s love (and in “Sonnet 18” the supreme master of English admits this with evident frustration.) The starting point of classical abstraction was “art for art’s sake,” a creation that doesn’t suggest or stand for anything other than what it materially is. Works by de Kooning or Calder use pure form as their subject, the gestural language of a brushstroke or the untranslatable effects of primary color on sheet metal curves and discs. Not worthy of mention are the frantic daubs and doodles local paint-and-sketch-club bastardizers of abstraction title after a random Vivaldi symphony or a day at the beach. Strong’s work makes abstractions of fragments of language that, while recognizable as human speech, are profoundly impenetrable, and that seems to be the point. It is what it is.

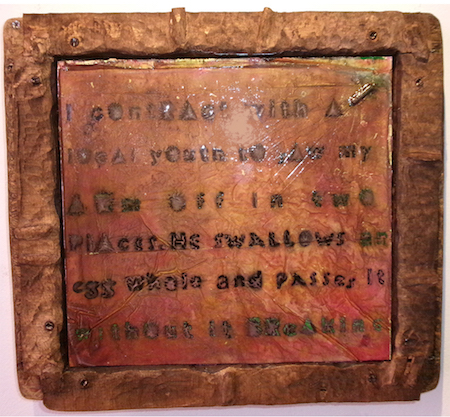

Along one side of the gallery are heavily lacquered, textual fragments in conspicuously hand made frames. The worn out wood salvage, solidly screwed together, intently tries to make something out of an indecipherable nothing, like Tony Stark trying to save his life by inventing Iron Man from scrap metal in a cave. The stenciled lettering on heavy paper or cloth, distressed by water or some other natural weathering, the artist has rescued from the process of decay just before the letters became less like spelling and more like the trail a slug leaves on the sidewalk.

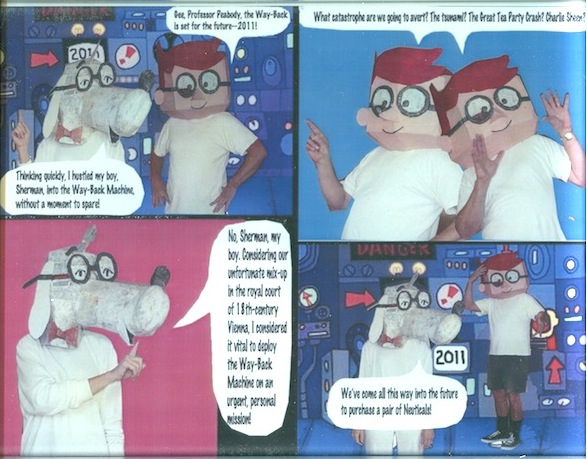

If David Lynch has a sampler hanging in his living room, it might say something like, “I contrast with a local youth to saw my arm off in two places. He swallows an egg whole and passes it without it breaking.” Another of Strong’s relics has Dr. Seuss-y looking whozits illustrating the text “Tied down with pheromone hair.” What can be made of these? The point is they refer to an empty cardboard box (pardon my metaphor). It’s a nothing presented with great human effort and momentous solemnity, like Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason or Wittgenstein’s Tractatus. Transcribing a wilderness with the crude tools at hand and makeshift language is meaningful only insofar as it gives us something to do: Grandma embroidered “Idle Hands are the Devil’s Workshop” and put her homily in a frame and hung it on the wall, too.

Opposite his yellowed, broken language Legos, Strong presents what could be their antidote: a series of stained glass windows, six-foot tall celebrations of light and color. They aren’t formal, churchly expressions of holy majesty, not pieced together with leaded strips or painted with the language of an Academic brush, but their idiosyncratic references to the natural world–fanciful plant and animal silhouettes–remind us that Creation, though it exceeds our critical understanding, nevertheless exists. Ultimately, our “network time killers” (to borrow a David Letterman expression from before he looked like one of the coughdrop Smith Brothers) to express the phenomenon of nature are inadequate, but we know at least that our lives exist in its loving embrace.

Transcribing the Wilderness surely is as immune to critical language as the extra-dimensional realities it nudges the visitor to contemplate. Strong produces one image, however, representing a clear-cut metaphor for the vanity of interpreting the ineffable. Let me take advantage of its accessibility to put it into words: on the border between the wall of lacquered fragments of tortured sentences and the colored effusions of light, he positions the semblance of a ticker tape machine, that device merchants of the material world use to calibrate the current market value of goods and man hours. As a means of explaining the true nature of human existence, such a machine, while connected to data coming in from all over the globe, describes our real life no better than the “Breaking News” reports from Forbes that interrupt my Internet surfing reveal meaningful events in the chronicles of mankind. Strong’s machine, suggested with a few, simple pieces of wood and a “found” bell jar, spews a long, meandering coil of ticker tape. The white strip has nothing written on it.

Family Show has Arms-Length Scope but Broad Reach

Suburban Wild, the September, 2021, show at Muse Gallery, features views of nature from the front door or back porch, making the point that every homeowner lives in contact with the flora and fauna of their local ecosystem. Foxes, goldfinches, and goldfishes abound, sharing lush lawns and flowering plants with a multitude of six-leggedy bugs.

With a keen eye for precisely those elements of a subject necessary to convey it and a deft application of brilliant oil colors from a mid-sized brush, Bonnie Mettler presents breathtaking glimpses of the animals who depend on our landscapes and decorative plants. The darting songbirds in 9 Goldfinches are either yellow-ish blurs or blessing the eye with a bright pose; a muscular iguana leisurely sips from a flowerpot on the patio picnic table. In Fox, a modest cottage on a grass lawn is the temporary destination of a wary red visitor. Mettler makes apparent the don’t-blink-or-you’ll-miss-it constraints on the stopping-by  of this stealthy pimpernel by representing him on a square patch of canvas glued to the pastoral background--a Schröedinger’s volpe.

of this stealthy pimpernel by representing him on a square patch of canvas glued to the pastoral background--a Schröedinger’s volpe.

Art preserves that which is elusive, explaining why every home features an aged picture in a frame, recalling, for instance, grandparents and uncles or the glimpses of bees and chipmunks half-hidden in the azaleas. Depiction of a recognizable image isn’t art’s sole virtue, however: artists also communicate an aesthetic and a way of understanding the experience of being alive. Thus, Mettler hasn’t only organized her show around appreciating the wildlife at arm’s length from every suburbanite; she’s invited her family of fellow creators to make their own contributions to Suburban Wild, asserting the immediate accessibility of critical and collaborative interplay between mothers, daughters, and sisters. The exhibit celebrates the virtue of anchoring oneself in the natural world and asserts the value of finding common ground within family. Artist! "Think globally; act locally."

Gail McIntosh, shares her sister Bonnie's wonderful gift with pigments and brushes and her eye for natural beauty. The collection includes a small canvas of orange and purple flowers beneath a bright blue sky, their stems darting wildy at conspicuous angles and swooping against dark, green leaves.

Setting aside these purely visual pleasures, daughters Kylie and Brett represent nature more ironically. A fox appears among Brett Mettler’s mixed media works who is screeching with jaws wide open and teeth bared, making a chilling, threatening noise that is unmistakable to the night traveler. A resident in London for nearly two decades,

Demonstrating a more lighthearted style than her sister, Kylin Mettler shows a similar penchant for appropriating industrial material--in mixed media constructions that fancifully suggest miniature “ungulates,” mammals with hooves. The menagerie of a dozen of these beasts represents a rattletrap of forks, keys, electronic hardware, and plumbing paraphernalia. Arrayed on a ledge beneath rhe gallery’s plate-glass front, these weird hybrids of machine parts and nature’s docile herds are “wild” in the sense that they appropriate from ready-made materials with exuberance and abandon. Consistent with the “backyard” fascinations of the older Mettlers, Kylin’s sculptures suggest homegrown ingenuity and that line in the Police song: “When the world is running down, make the best of what’s still around.”

Of the principals around which an exhibit featuring various artists may be organized, is any so natural as six women in the same extended family? Art movements are ugly, loose-fitting garments, and art collections are stamped with the coarse sensibility and personal fortune of some oligarch, probably. Just a guy who wasn’t an artist and whose family made their fortune concocting patent medicines with which to torture syphilitics--or some damn thing. Ah, but a show celebrating the diversity of approaches and motives in an all-woman group of artists! Their shared personal history posseses a natural inevitability, and no biological unit inspires both diversity and common cause so well as a family. Suburban Wild refers to an organic appreciation for

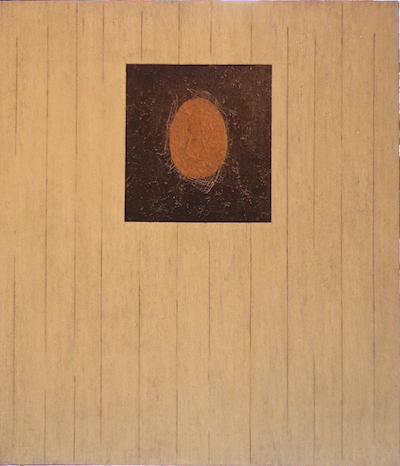

In the present show, no sensibility is more eccentric and beloved than that of Bonnie Mettler’s sister-in-law, Nancy Bruce. Bruce’s large, mixed media works utilizing collage assemblages represent the eternal mystery of the backyard chicken and her many eggs. The various textures in these pieces are displayed on a coarse wallpaper-y material resembling a whitewashed fence. Through an opening in various framed “coops,” we observe several cartoonish hens meditating on their unborn chicks. In one piece with four openings in the common wall, roosting anxious moms chant simultaneously, “I wish I were an emperor penguin.” A chicken in another coop dances in purple stockings, forgetting for a moment her relentless maternity. A perfect real-world analogy to abstract minimalism hangs in the gallery’s front window: a square, off-center opening in a whitewashed fence frames a brownish egg (O, perfect orb!) presented in a nest of woven strands against a cosmic blackness. Bruce tersely documents the existential dilemma of motherhood with a world-weary sense of humor.

Also egg-shaped with brittle, glazed surfaces are the simple clay pots of Maisie Osteen, daughter of Gail McIntosh, niece of Bonnie Mettler, and cousin of Brett and Kylin. The vessel’s outsides are colorful containers topped with frogs or other backyard commonplaces, one of them featuring Kylin’s yarn-formed rendition of a homey caterpillar. The exteriors are rich and expressive; their interiors are mysterious projections, ultimately unknowable. One ceramic in particular, named A Flock of One and topped with a dour sheep, represents the problem of going your own way yet being a part of a large, demonstrative family.

Mightn't one’s own development be crushed under the weight of family connections? Their burden is real, unavoidable--and with life experience, more desirable than they were in our youth. In Suburban Wild, a show about cultivating an awareness of the life teaming in one’s immediate environment, the problem of being an artist seems also to resonate: while one is conscious continually of the burden of mounting a grand career on the world stage, the interplay and encouragement of a nuclear family of artists affords huge compensations. Affirmation! The heritage of a common history is our most certain legacy, and to be esteemed in one’s own backyard a rich reward.

Drew Zimmerman, 2021

Susan McKee: The Invisible Superficial

Sometime in Art's murky past, the subjective world view triumphed over the public version (don't worry-- there'll be a rematch), and since then, painters have represented the hopelessly individual nature of experience with various technical schemes. The adjacent application of complimentary primary colors in Impressionism refers to Newton's work on optics and the idea that a viewer actually mixes colors in his or her brain; the grids and fragments of Cubism are a reaction to the falsity of imposing a single, physical perspective on that same viewer. Ironically, artists relied on color systems and prescribed techniques to expose a fundamental truth about experience: that it is by nature unpredictable, unsystematic, and wholly susceptible to the irregularities of an individual observer.

I'm not condemning Seurat or Braque for their inconsistencies because every plan to depict reality is equally doomed. Magritte's "This is not a pipe" seems to me the only irrefutable utterance in art criticism. In a discussion of painting, one must accept the existence of any number of technical metaphors for the ineffable object depicted within the frame and accept that a representation of the real is not reality. The very best we can hope for from a painter is a thoughtful, stylish projection of their own faculties in reference to a mutual, but misunderstood, multiverse. (I know you're out there: I can hear you writhing.) Disregarding all that tautological drek about art for art's sake and painting about painting, every art work is ultimately about the person who painted it. We look at their work and compare our own experience of the world to the artist's. And then, we plan lunch or pack the car, however we interpret new information. Painter by painter, it takes years of painstaking work to acquire a mere simulacrum of all that stuff out there, but, oh, the people you meet, the places you go!

Susan McKee's current [January, 2014] show at Muse Gallery conveys a quirky and often lonely version of existence through offbeat subject choices and the artist's expressive brushwork. She calls the collection of bright canvases "Glimpses," indicating the impossibility of presenting a comprehensive record of that which is viewed. We are inside Plato's cave, people, inferring a leafy, sun-dappled outside that may only be understood secondhand. Ms. McKee knows no better than you or me how to interpret life's phenomena, but she's a valuable witness with a tone that's humble and humorous and common-sense insecure.

A man toolless or a tool manless--Take your pick!-- signifies the condition of futility and unfulfilled purpose into which we have awakened. For instance, one of Ms. McKee's paintings abstracts the Maytag guy from those iconic television commercials featuring the "loneliest man in town." Clearly, every worthwhile artistic career is similar to that of the isolated repairperson, possessing a wealth of skills in vain, since Truth and Nature will never yield to them. The painting Bring Your Own Bike describes an abandoned, red, two-wheeler, leaning against a weathered facade, a perfect expression of some absent "other" and more than that, a delightful means with its cause deleted. McKee incises the painting's title into a colorless layer, graffiti in the whitewash. She's adept at producing transparent layers of paint that give the work a gauzy atmosphere, a fog over the proceedings, a technical means to express a wistful nostalgia, the persistence of loneliness, and the weakness of memory.

"Glimpses" contains shots of pretty women, the white vinyl,  knee-high boots of a drum cadet and a row of leggy babes under globular hair dryers. Ms. McKee's subjects and titles (Soldier Boy, Sweater Girl, Maytag Repair Man) fix her in a particular generational cohort, so we can see her coming. The banal familiarity provides a comfort zone so she can do something truly subversive, which is to use a technical mastery of her materials to suggest what she does not have and can not acquire.

knee-high boots of a drum cadet and a row of leggy babes under globular hair dryers. Ms. McKee's subjects and titles (Soldier Boy, Sweater Girl, Maytag Repair Man) fix her in a particular generational cohort, so we can see her coming. The banal familiarity provides a comfort zone so she can do something truly subversive, which is to use a technical mastery of her materials to suggest what she does not have and can not acquire.

As avarice is the refuge of the stupid man, and religion is a balm for the uneducated, art is control for the helpless. McKee in charge! The woman in Sweater Girl is strikingly beautiful and engaging, but the artist doesn't fuss over the details. The sweater is a lush, deep, wool-knit blue and the woman sits transgressively on the side of a table. She leans toward us with an "It's your move!" expression. The paint here is a patchwork of opaque and transparent sections blending depth of rendition with a purposefully superficial eye. Memory is inexact. It has lapses. Boy, does it have lapses.

This artist, Susan McKee, in this show at Muse Gallery, is a virtuoso of presenting the limits on perception. She probably wasn't thinking about Immanuel Kant's bicycle when she painted the postcard shot for "Glimpses." Kant argued that we never actually see the quality of bikeness, but we have it in our heads, an image suggesting every aspect of the subject. Great! So now I have that going for me. But this a priori bicycle we see is not the thing itself. Our view is too particular, fixed, shaped by our own random experience to truly encompass the whole. We make do, but the human condition is essentially an anxious exile to five senses. Shouldn't there be more? And where's my jet-pack?

I love the side-by-side pictures of the Wicked Witch of the West getting in Dorothy's face and a row of trees McKee calls Out of the Woods. The witch's hands are clawing, grasping against Margaret Hamilton's chest, there, and little Judy looks up at her, helpless. But the child's expression isn't fear, exactly: it's more a look of nonplussed anxiousness. The danger our witch represents kicks in against us only if we engage it.

Thus, the trees in Out of the Woods are a row or two deep, a barrier in the sense that those padded contraptions on a football practice field are barriers. They only impose themselves if one takes up the sport. McKee allows that she suffers a sort of self-imposed anxiety that's part and parcel of choosing to make art, exerting self-limited control over an environment she can see but dimly.

Click on this link to return to Top of Page or Table of Contents.

PLEASE PATRONIZE OUR GREEDY AND CRIMINAL CORPORATE SPONSORS

YOU KNOW YOU STILL WANT TO!

Four Stages of Human Consciousness

Muse Gallery 36th Anniversary Show

Philadelphia's oldest artists' co-operative gallery celebrates its longevity every December with a group show. Because they have successfully and democratically responded to stress in their environment for so long, Muse Gallery has much to celebrate. I admit my favorable bias in that I was a member of Muse Gallery until fall of 2013 (and its director for 18 months), but here then is first-hand witness to the amazingly vital functioning of the organization. Name me another endeavor of equal complexity managed entirely by collaborating artists? Hell, even the Traveling Wilburys folded eventually.

One skill that stays razor sharp in a group like Muse is hanging a show. Someone always volunteers to do it, gets three others to form a committee, and has the gallery ready for First Friday traffic before you can say, "I'll bring the cheese." When twenty or so artists are each showing one or two pieces, an affinity of colors, shapes, and textures guides their arrangement, and visitors especially appreciate a straight categorization according to non-verbal cues. Kathryn Lee's paper collages Blue Engine and Red Engine, so bright and warm, looked splendid in the back of the space next to Deann Mills' large abstract, I'm Busy. Ms. Lee, a former book illustrator, always exhibits the most marvelous, colorful constructions in three dimensions, compositions of purely abstract forms mixed with references to actual objects. Sometimes she mixes her own colors and paints paper stock, and other times she uses already colored papers, twisting and folding them to make forms that stand out from the white mounting board.

I often see purely abstract work that makes me think the artist has exhausted his vocabulary of shapes.

The sculptor Etta Winigrad has been with Muse Gallery longer than any member artist except Lorraine Raywood, the resident mixed media and photography wizard. They remember when the gallery was a women-only collaborative. Ms. Winigrad's ceramic work follows a process of her own adaption where, in the final phase, the raw clay is exposed in the kiln to various burning woods for the effect the smoke creates on the crystallizing surface. More amazing than that is Ms. Winigrad's quirky extrapolation from the human form that is at once innocent, a bit primitive, and endearingly expressive. Around and Around makes material a head filled with too many ideas and things simultaneously. In a halo circling his brow, a key, furniture, sporting equipment, a lightning bolt and other Monopoly-set tokens represent a churning of consciousness. The skill with which the work is assembled and realized can't be overstated in the case of this superbly refined professional whose sophisticated sculpture always maintains a childlike grace.

Around and Around makes material a head filled with too many ideas and things simultaneously. In a halo circling his brow, a key, furniture, sporting equipment, a lightning bolt and other Monopoly-set tokens represent a churning of consciousness. The skill with which the work is assembled and realized can't be overstated in the case of this superbly refined professional whose sophisticated sculpture always maintains a childlike grace.

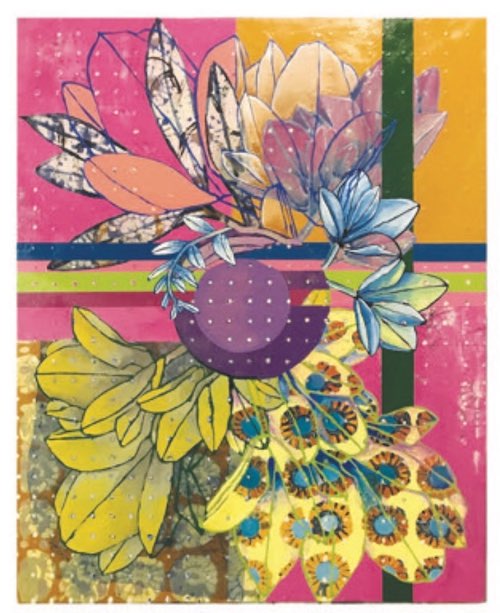

In contrast to Ms. Winigrad, the printmaker Terri Friedkin has been a member of Muse Gallery for less than a year, but like her colleague, she creates her own path. The last prints I saw by this artist had a texture suggestive of computerized typing; in Unleashed she uses an array of perforations in a block of color that reminds me of modern building materials or even Ben-Day printing dots, but in any case they're human artifacts rather than forms from nature. Ms. Friedkin suggests a lot with very little. I wonder if the windows-like forms of Mark Rothko influenced the composition in this anniversary exhibition. She shares that artist's skill at creating transparent panes of color and the endless permutations to be gained by overlapping them.

Sara Bakken's three-dimensional Environment is made of silk organza and glass, and, once again with these Muse Gallery types, she is applying her own process to the materials. Ms. Bakken distresses the silk with heat to make nodes and uses hand-blown, often sand-blasted, glass to complete the delicate forms. Frankly, I have no idea how she holds the sections together: is it done with string? surface tension? centrifugal force? In the past, her work has studied simple organisms that live in very deep seas, and the work in this show also celebrates nature's elegantly abstract forms dwelling in that part of creation most alien to man.

Diane Lachman is a professor of color. I'm not making that up or being hyperbolic. She taught in the University of Pennsylvania's fine arts program, but retired when they made color an elective course for undergrad artists. (The same damn-the-foundations-let's-build-a-house enthusiasm has erased grammar from every college English program I know.) Ms. Lachman's canvases have always been about the juxtaposition of different hues and tones, and her compositions have featured abstract arrangements of grid-like boxes or floating lozenges.

Diane Lachman is a professor of color. I'm not making that up or being hyperbolic. She taught in the University of Pennsylvania's fine arts program, but retired when they made color an elective course for undergrad artists. (The same damn-the-foundations-let's-build-a-house enthusiasm has erased grammar from every college English program I know.) Ms. Lachman's canvases have always been about the juxtaposition of different hues and tones, and her compositions have featured abstract arrangements of grid-like boxes or floating lozenges.

Warp and Weft continues a series from her last Muse exhibition in which the picture grid breaks into pieces, not like a jigsaw puzzle, but like some four-dimensional, geometric construct that requires special technology to be expressed in our visible three. The artist provides a separate schematic with each piece that spells out precisely how the parts of the whole should be displayed on a wall. In my experience with Muse Gallery artists, Ms. Lachman's resourceful and inventive approach to realizing a personal vision is very much the norm. Perhaps the quality that best predicts membership in this co-operative isn't frustration with the commercial gallery scene in Philadelphia, but a wholly individual approach to the use of familiar materials.

Creative Force Made Real at Muse

Sara Bakken’s silk and glass constructions at Muse Gallery this October recall the moment in some dark and unknown past when random proteins, minerals, and water,

The artist learned her vocabulary of basic forms during a period of experimentation and deliberate inventiveness; no one gave her technical instructions. Shaping the white silk or shaping the glass involves stressing the materials using heat, stretching, and probably occult practices. Ms. Bakken’s ingenious constructions utilize the shapes she needs to articulate existing deep sea critters, and multiplication is one of the strategies she deploys to assemble a likeness.

Because the subjects consists of such pared down forms, we might not recognize them as actual denizens of Earth and appreciate them as abstractions.

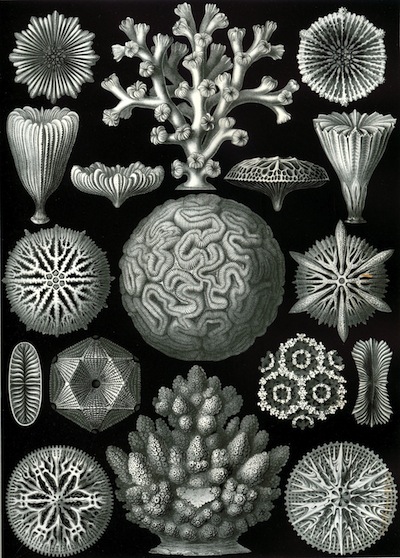

She isn’t the first to focus attention on the bounty of purely organic, natural life forms drifting under the sea or to recognize in them the stripped down tool kit of life and the basic forms of sculpture and brushstroke. Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) discovered and named thousands of species (probably some of the same that fascinate Sara Bakken), and he generated a tree of life showing the relationships between life forms. Stem cells and ecology were among the words he coined.  Besides being a biologist, he was an artist, producing dozens of elegant paintings of anemones, discomedusae, and radiolarians. Haeckel embraced as aesthetic and scientific treasures the order and symmetry of simple organisms, many of them combined into large communities organized to perform functions so simple they are nearly chemical not biological.

Besides being a biologist, he was an artist, producing dozens of elegant paintings of anemones, discomedusae, and radiolarians. Haeckel embraced as aesthetic and scientific treasures the order and symmetry of simple organisms, many of them combined into large communities organized to perform functions so simple they are nearly chemical not biological.

All artists produce in a recognizable style distinguished by the telltales of their own hand and their idiosyncratic reproduction of what the eye sees. Sometimes the artist cannot reveal their hand in a work except through daunting complexities. Sara Bakken developed processes to transform silk and glass, and uses them elementally to copy forms in nature. By keeping to a trajectory that stays close to nature’s simplest expression of the lifeforce, she invites us to enjoy the similarities between compulsive artistic and natural creation.

At left, an illustration by zoologist and draftsman Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919), "Maeandria Hexacoralla."

Artists Interact in Dynamic Muse Show

You could make yourself crazy waiting for the art-going public to treat your art to even a complete sentence of reaction or criticism. Maybe people are fearful of divulging what moves them in a work because they believe one should have training in art criticism first, before being entitled to an opinion,  though I doubt it since the public considers higher education so much ivory-tower mumbo jumbo. Maybe visitors to a gallery are afraid to express their positive feelings about an art work out of reluctance to be identified with a losing cause, just as I know Philadelphians who love baseball but won’t admit to being partisans of the Phillies. Or maybe visitors to a show think “Awesome!” or “Neat!” alone are useful criticism without offering supporting details of any kind.

though I doubt it since the public considers higher education so much ivory-tower mumbo jumbo. Maybe visitors to a gallery are afraid to express their positive feelings about an art work out of reluctance to be identified with a losing cause, just as I know Philadelphians who love baseball but won’t admit to being partisans of the Phillies. Or maybe visitors to a show think “Awesome!” or “Neat!” alone are useful criticism without offering supporting details of any kind.

Many examples of vivid personal reactions to art appear in Muse Gallery’s June 2016 show “Containers and Boundaries,” a joint exhibition by Bonnie Mettler and Kylin Mettler, mother and daughter artists who react to one another’s work by physically adding to it. Unlike the passive viewing we are used to in a conventional show, this installation provokes a dialogue between artist and highly engaged viewer, and their demonstrative reactions become the focus of the exhibit. The show’s call-and-answer formula gives visitors a small window into the vast landscape of the creative process. It also says much about the Protean nature of being, where labels such as “mother” and “artist” blend seamlessly or assert themselves and their primacy.

According to the notes to the show, "'Boundaries!' was a short cut word in [the Mettler] family that meant:'You have crossed the line into my territory. I love you, but step back.'" Recognizing that everyone--and especially family members--is entitled to assemble a personhood and defend it from outside challenges, the Mettlers also name the conditions under which artistry takes hold and develops.

In the piece Right to Assemble, Bonnie Mettler depicts a grouping of fragile containers that seem to be under the threat of a destructive, grinding machine. Kylin Mettler comes to the rescue by recreating those threatened pieces in three dimensions, effectively preserving them from harm.  "Right to Assemble" not only refers to a constitutional prerogative, it calls to mind assembly as a description of what artists do, as in the work of Joseph Cornell and his use of museum forms to represent the accumulation and preservation of identity. As a boundary is an ever shifting but autonomous territory with its own rules, a container refers to a static accumulation of memories and objects that is the self.

"Right to Assemble" not only refers to a constitutional prerogative, it calls to mind assembly as a description of what artists do, as in the work of Joseph Cornell and his use of museum forms to represent the accumulation and preservation of identity. As a boundary is an ever shifting but autonomous territory with its own rules, a container refers to a static accumulation of memories and objects that is the self.

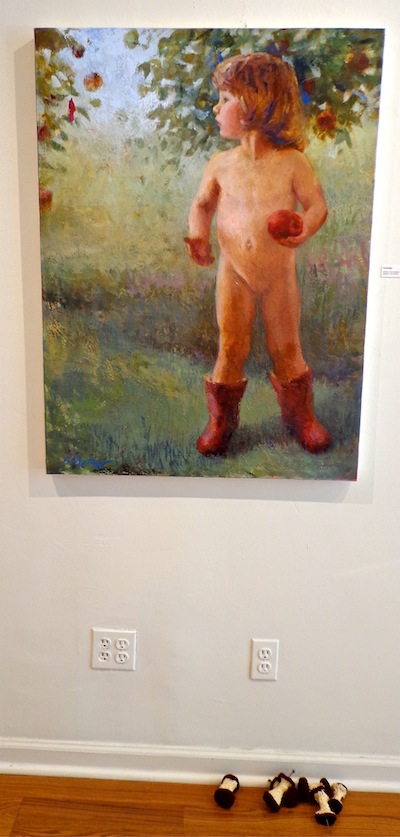

Kylin Mettler selected her mother's painting Knowledge for inclusion in the show, a vivid portrayal of herself as a naked child next to an apple tree and holding a piece of fruit. Kylin's expansion of the frame is a small pile of crocheted apple cores on the gallery floor under the portrait. Only the child of an adept portraitist who has grown up next to a parent's vision of their infancy can appreciate the effect of the portrait's depiction, at once glorifying and categorizing. Kylin's additions create a broader period of time than Mom's portrait by itself inhabits and extends the knowledge of the artist's child into an art sensibility of her own. By adding the representation of her own maturity to the heirloom, Kylin Mettler hijacks the image and controls its meaning.

Mother Mettler proves that two can play the game of changing the boundaries around a work of art in her additions to a pair of her daughter's pieces, When It Wasn't and Almost Baby. Kylin uses a crotched blanket with squares flying loose from the main organization to symbolize a deeply personal conflict threatening her marriage. When It Wasn't uses linoleum-block prints to show the artist experiencing the grief of her relationship's collapse.

With a steady pencil on the gallery wall, Bonnie Metler draws a thin frame containing the blanket and its disruption. The addition suggests the unity of her daughter's experience. "It is what it is" is a modern colloquialism representing reconciliation to catastrophic events, an attempt to categorize particularly painful occurrences as not implying shame or guilt to those who suffer by them. For the companion piece that shows Kylin in attitudes of grief, Mother has drawn with her pencil on the wall a strand of barbed wire. The artist is also a mother, defending by whatever means her aching daughter.

None of the oils Bonnie Mettler is exhibiting in Containers & Boundaries have frames, which in a post-Modern world means more than thrift or insufficiency. We should supply boundaries and lock in our labels only with a heavy dose of irony. Any meaning derived from experience is arbitrary and words express the right to dissemble. The late novelist David Foster Wallace employed the device of footnotes in his fictions to represent the impossibility of finding the last word anywhere. The June 2016 show at Muse Gallery contains about fifteen installations where artists transform the meaning of various works by thoughtful additions to them. Along the way, they invite visitors to consider the tentativeness of categories of art and, by extension, the labels we apply to ourselves.

--Drew Zimmerman, 2016

Notes on The Mystery of Bitter Root Manor

In 2014, a quite remarkable work of over 25,000 words in pentameter verse was slipped over the transom anonymously to our sister station, TexEditing.com, the copywriting resource for people in the arts

community. The format of the work bears examination, since it is consistent with ideas I've written about in the past, especially in "Why I'm Not On Facebook Any More." To tell the truth, pretty much everything in these blog pages is consistent with the attitude expressed in The Mystery of Bitter Root Manor. What a relief: I thought I might have to finish out the rest of my days in the absence of understanding from my peers!

community. The format of the work bears examination, since it is consistent with ideas I've written about in the past, especially in "Why I'm Not On Facebook Any More." To tell the truth, pretty much everything in these blog pages is consistent with the attitude expressed in The Mystery of Bitter Root Manor. What a relief: I thought I might have to finish out the rest of my days in the absence of understanding from my peers!

The work is in rhyming verse–over 50 chapters and three acts of it–describing the adventures of a behavioral psychologist/chemist and his sexually expressive children and grandkids. In almost every instance, access between different locations in the story requires knowing a password taken from three categories of trivia: the guest villains on the 1966 Batman television series, performers of various theme songs for the James Bond franchise, and questions regarding the names of songs and album titles by The Beatles.

The trivia answers are difficult enough, one supposes, to be daunting to the casual reader, although close attention to the words in the poem usually gives more than ample clues. Could Anonymous have imagined, as I did when I read the beginning of his or her poem, stacks of readers hung up in The Great Hall, trying to remember that Anne Baxter played Olga the Cossack Queen on Batman? The point of the tough trivia exercise is likely not to quickly disqualify every potential visitor

to Bitter Root Manor but to insist on active reading of the work instead of passive "barking at print." Expressing a fatalism about reader participation, Manor’s anonymous poet writes, "The secrets hidden a reader could find/ Blah, blah, blah, and if he-she had the time/ Well anyway, in these rooms they are writ/ With treasure to win if you give a shit."

to Bitter Root Manor but to insist on active reading of the work instead of passive "barking at print." Expressing a fatalism about reader participation, Manor’s anonymous poet writes, "The secrets hidden a reader could find/ Blah, blah, blah, and if he-she had the time/ Well anyway, in these rooms they are writ/ With treasure to win if you give a shit."

For a work that can only exist in a hypertext environment (its pages linked together, not bound, and every one illustrated with photos and animations), the story of the dynastic Archers acknowledges that it must be primarily read, not watched or scrolled. Anonymous drops off a magnum opus on a thumb drive then backs away from it, leaving the thing on the doorstep of an illiterate culture, content to have its crucial morning brief leaked drip-by-drip through corporate-sponsored filters, Fox News, and Americans for Prosperity. Requiring the reader to engage with the text by passing through frequent checks of its content has the whiff of boomer nostalgia for erudition, a common culture, and a time when it was the duty of every citizen to be well informed and able to discriminate between legitimate sources of information and propaganda.

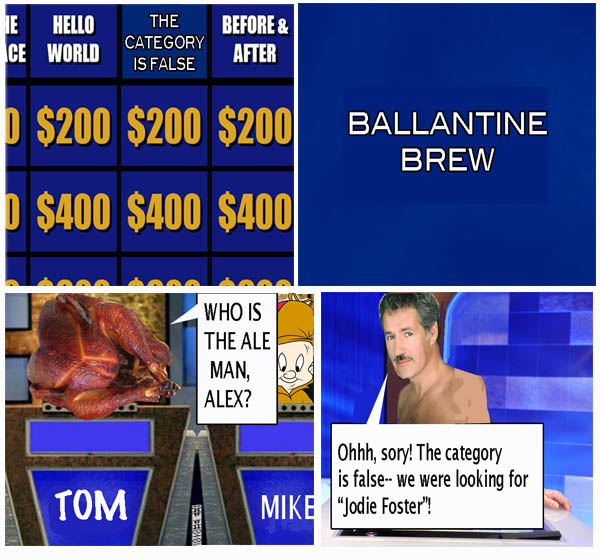

The Mystery of Bitter Root Manor depends on the reader’s knowledge of pop culture trivia to move from

room to room of the text. Given the unlikelihood of any visitor to these pages knowing names like Glynis Johns (Batman’s Lady Penelope Peasoup) or Matt Monro (he sang the theme for Bond’s From Russia with Love), Anonymous apparently values simple Internet scholarship so much as having a memory suited to play Jeopardy! We are invited to refer to extraneous sources that referee matters of an empirical nature. Go ahead: google the answer; read the marvelous tables on Wikipedia covering who played the villain in every iteration of the BM franchise and every theme song that played while some naked ingenue was projected onto Commander Bond’s gun. A simple, scholarly gesture signals adherence to a whole system of facts, causes, and effects.

room to room of the text. Given the unlikelihood of any visitor to these pages knowing names like Glynis Johns (Batman’s Lady Penelope Peasoup) or Matt Monro (he sang the theme for Bond’s From Russia with Love), Anonymous apparently values simple Internet scholarship so much as having a memory suited to play Jeopardy! We are invited to refer to extraneous sources that referee matters of an empirical nature. Go ahead: google the answer; read the marvelous tables on Wikipedia covering who played the villain in every iteration of the BM franchise and every theme song that played while some naked ingenue was projected onto Commander Bond’s gun. A simple, scholarly gesture signals adherence to a whole system of facts, causes, and effects.

Besides connecting itself to the great, pop culture library in the sky, a recurring theme in Bitter Root Manor is the postmodern assumption that whatever we need to know as a race is readily available somewhere, but we walked right past it or lost it in our files. (Is the library at Alexandria still on fire? Has it ever not been?) Modern life is an overwhelming deluge of facts, figures, and bat-shit crazy interpretations of them. Behind every trivia question is the lowly Jeopardy! writer who editorially organizes names and places into a Venn-diagram circle-within-a-circle representing “things a sentient person is likely to know.” The rest of life's dross is so hopelessly obscure it will become a mere footnote someday, like the entire Justin Bieber catalog. Which among the barrage of facts we receive is an actual cultural touchstone, and what might we thankfully forget with time, when our Doctor Oz and Marcel Ozuna wounds have healed?

The lively and often ribald poet evidently is a product of the 60s and speaks directly to other members of his or her cohort, the core of the Baby Boomer generation.

Consider these while here and there you go

As we assess the crusts of what you know,

Leftover from the appetite you sate,

For heaps of flesh and blood upon a plate,

A bit of quid pro quo to spice a game

Of which of Batman's villains can you name

Some trivia we'll get to soon enough

That unlocks locks and panels when it's rough.

While, on the one hand, Bitter Root Manor rewards readers for remembering names from a palette of pop culture highlights, at the same time, the very nature of a password is that it has to be written down somewhere, even if it temporarily drops out of immediately accessible, human memory. Indeed, Bitter Root Manor’s secret passkeys are compiled in a single convenient .html document and shoved in a hidey-hole. The maze of the story, leading from room to room in a jumble of events and perspectives, has a secret map with embedded links that catapult the user to any location instantly.

I never played those bloodbathy first-person shooter, video games, but I was vaguely aware of my teenage son playing them, and how he acquired special codes that gave his avatar unlimited “lives” and gnarly superpowers. He could only be accused of not winning those video games "fair and square" by someone who was unaware of the real playing field of the contest, which clearly included sellers of secrets and the largesse of the highest of the high. One is excused from “not knowing,” because, after all, ignorance is only temporary, the easiest of all cognitive deficits to remedy. All the traveler has to do is spot the likely niche in which the secret key is hid (you don’t need a password to access it!) or, better still, find a more accurate reader who will share what they know. Let me tell you something about meritocracy in America. I teach the SAT, which started as a game-leveler in the "competition" for college admission. Its mission, today, is the same as it ever was: success on the SAT is available equally to anyone who can afford me as their tutor.

What should we make of a story that permits the reader to dispense with following a particular sequence

of plot events by making available the technology to skip from location to location and the various pressure points in the story each setting represents? A primary characteristic of postmodern fiction is acknowledging the falseness of all plots. In fact, time and space, even cause and effect, are an illusion. You could look it up. Additionally, Anonymous recycles themes and imagery from their own work and pop culture at-large (superhero comics, 60s sitcom TV, an obscure animation Chuck Jones did for Bell Laboratories) to expand beyond any single file or folder the world in which the web-based story exists, intertextuality being the hallmark of the most important works of fiction created since the 60s.

of plot events by making available the technology to skip from location to location and the various pressure points in the story each setting represents? A primary characteristic of postmodern fiction is acknowledging the falseness of all plots. In fact, time and space, even cause and effect, are an illusion. You could look it up. Additionally, Anonymous recycles themes and imagery from their own work and pop culture at-large (superhero comics, 60s sitcom TV, an obscure animation Chuck Jones did for Bell Laboratories) to expand beyond any single file or folder the world in which the web-based story exists, intertextuality being the hallmark of the most important works of fiction created since the 60s.

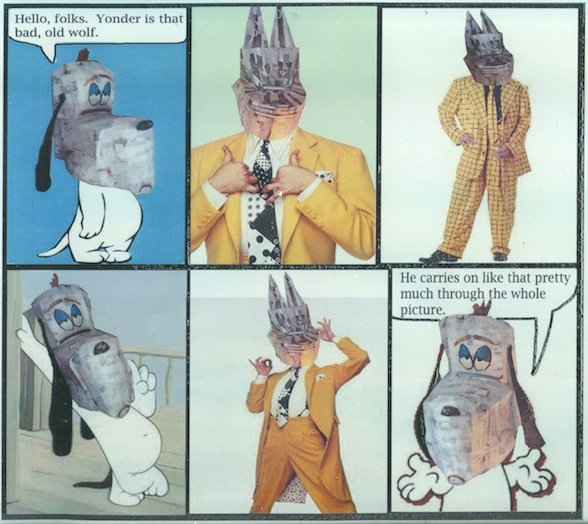

The first act of BRM's comical rhyming couplets is devoted to Batman trivia. The choice seems auspicious, and not only because the show is so fondly remembered. Adam West was a notoriously stiff performer, which helped to make the series the campy gem it was. Creator Lorenzo Semples, Jr., who passed away in March 2014, a month before Anonymous sent out his or her Batman love letter, intentionally built his show to read ironically; for instance, he originated the idea of giving ordinary objects a Bat-prefix. Camp is an essential aspect of the postmodern sensibility, and we can date it aesthetically to Susan Sontag's 1964 essay for The Review which determined its 58 separate features, chief among them artifice and exaggeration. Like the "Pow!" and "Boff!" caption cards that narrated Batman battling Penguin in a dimension outside their sitcom space, the carefully constructed "extra-textual" notes and disclaimers surrounding The Mystery of Bitter Root Manor highlight its artificiality, and its spy movie/comic book trappings include it in a discussion of Terry Southern's work for Candy (1968) and Dr. Strangelove (1964) with a lovely dovetail to the Beatles, swinging London, James Bond and Casino Royale (1966). Or, would you believe Get Smart? Anonymous remains self-effacing, self-referential, and multi-textual, so much it will make you plotz.

The writer of The Mystery of Bitter Root Manor and its fifty or so .html pages has chosen a form that is adapted to the Internet (although the rhythm and rhyme suggest Homeric epics or something equally dusty). The first-person video game presentation of the story divulges its essentials randomly, the reader encountering events associated with a particular place--not a particular sequence-- as they move from room to room in the titular mansion. It can be said that the medium of the work is .html code and the basic feature of its format is a browser window. The Internet, after all, is the crucial technological development conditioning us to view the world through a tiny peephole that fails to encompass the vastness of human experience or history. Irony supplants knowledge. We are each a laser-beaming Observo, whose superpower is attention to present styles and perspectives. Who’s even trying to generate a narrative that ties all those different portal views together?

As Art Linklater used to say on the box cover of the Game of Life, I heartily endorse the game-like randomness and wisdom of this sprawling and profane adventure. Consider The Mystery of Bitter Root Manor three acts in search of a reader; don't go by me, but Pirandello over to TexEditing.com as soon as you can to see for yourself.

Click on this link to return to Top of Page or Table of Contents.

PLEASE PATRONIZE OUR GREEDY AND CRIMINAL CORPORATE SPONSORS

A Brief Re-Cap of the Winter of '14 (LONDON, 26 Jan 2014) A couple visiting the Tate Modern museum here permitted their toddler to climb into an important Donald Judd minimalist sculpture as visitors to the gallery looked on in horror. The transformative moment was photographed by another visitor, Brooklyn art professional, Stephanie Theodore. Additionally, she told the parents of the dimension-shifting child they were letting him use a million-dollar abstract art work as a toy, to which they replied, "You know nothing about children." That may be true but I know what I like. If You Don't Agree with Me, Considering "Last Days" with Pompeo Using Art to Excavate Her Story Brightening the Study Hotel at University City, Moon Garden is Rashidah Salam's exhibit of biographically themed paintings in acrylic. The artist represents the accumulation of her personal story in the depth of layers of paint applied to a blank canvas. The first member of the Drexel faculty to show in the space adjacent to the hotel lobby, the Malaysian-born artist suggested to me that narrative, flattened as it is to the two-dimensional plane of a canvas, exists in space but not in time. The mind randomly stacks memories, one-atop-another, disregarding when the image was first assembled in our interior Photoshop. Rashidah Salam has a philosophical attitude towards her history, a disciplined acceptance that could have been learned from the discipline imposed upon any artist trying to represent lived experience with fussy pigments on a canvas. The surface changes; that much is inevitable. We can be the instrument of change, but the especially forceful acrylic paint imposes limitations. The gardens in Salam's work abound with life and possibility, but, she says, a painter is "stuck with the garden she has." Perhaps, she means the universe of opportunity that opens before the practicing artist will nevertheless be bound by that person's own history and their lifelong habit of repeatedly working out the same patterns on the unformed canvas landscape. Carolyn Harper Drapes a City's Invisibles in Brilliant Cloth By January of 2021, the phrase "in the middle of a pandemic" has come to express a wonder over the audacity of committing any number of mundane acts, considering. Carolyn Harper's Muse Gallery show Circle Gets the Square: Jim Kippen and Maureen Drdak A pair of artists who have been members of Muse Gallery in Old City, Philadelphia, demonstrate to me a striking contrast in the way an individual artist uses technical facility to approach the thorny problem of personal expression. Jim Kippen's work typically uses square shapes to represent man-made objects, and Maureen Drdak favors the circle to symbolize natural creation. Constance Culpepper:

As Horrified Visitors Look On, $M Abstract Sculpture Becomes Real

"I couldn't believe my eyes," opined Judd partisan Doug Heller, who is himself in an abstract state, having died two years ago. "The whole point of the work is to represent pure form, and here in a flash some random three-year-old makes it into a chest of drawers at granny's, catching everyone unprepared. I'm devastated." Asked if he would reconsider the work now that its reality was confirmed, the late Mr. Heller said, "Certainly not. My opinion of Judd and his work remains the same. He's the best!"

Life is too short not to take your turn!

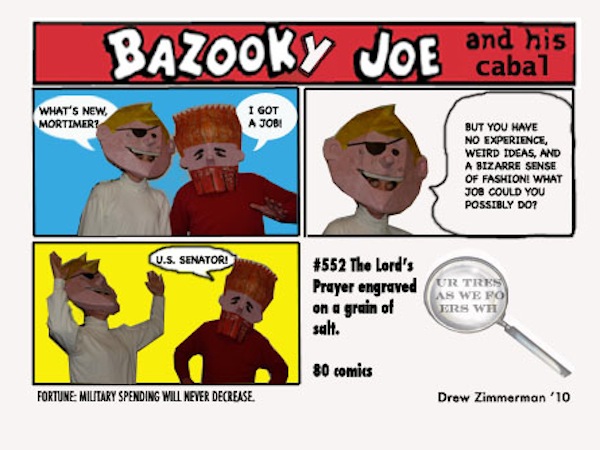

COMIC STRIP COMICS

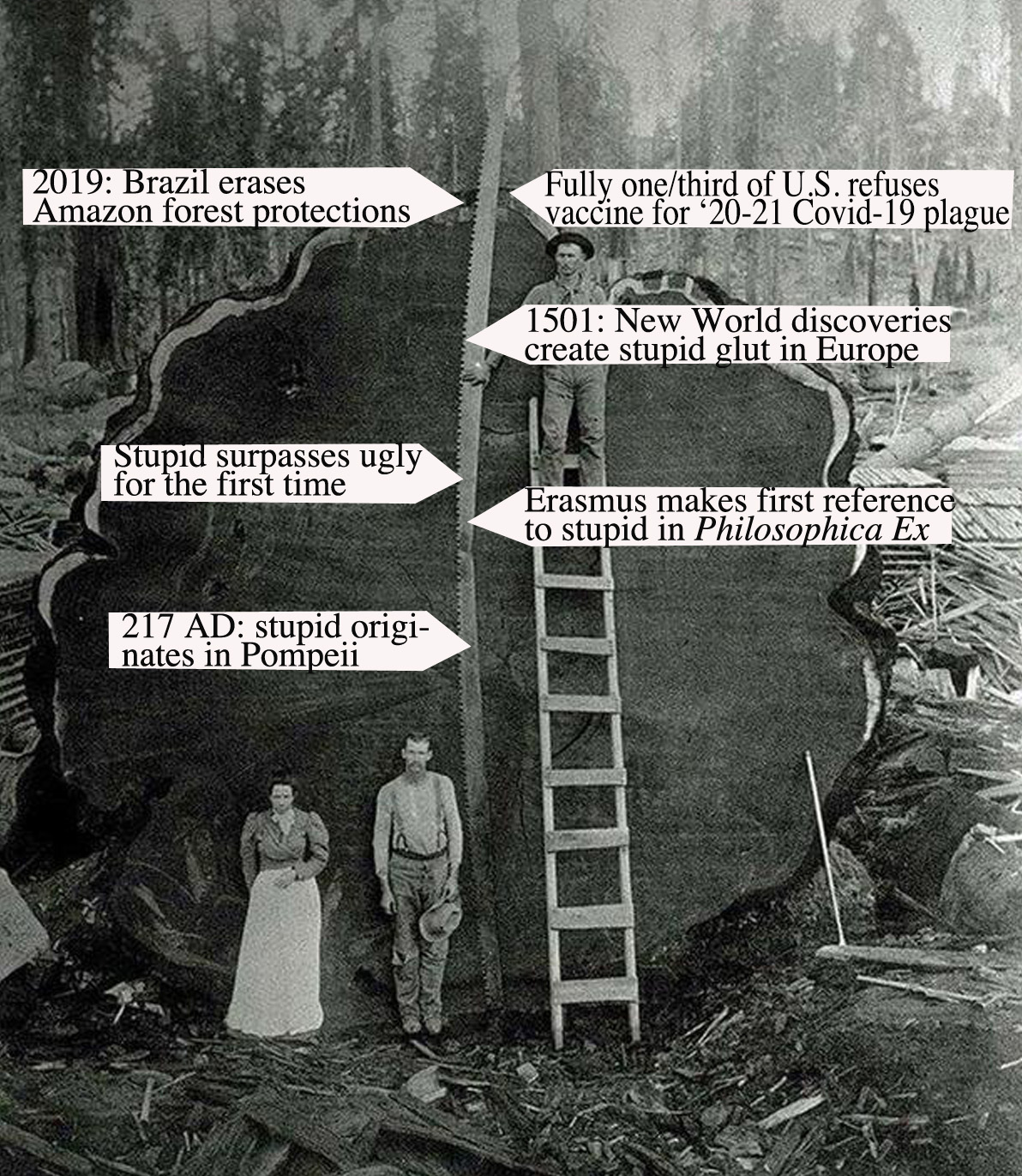

You're Stupid: A Scientific Approach

The human brain evolved for a single purpose: not to make money, not to make angels, but to give mankind a shot at survival in a neutral environment that doesn't care about us one way or the other. The greatest asset we possess as a species, slugging it out against forces bent on our destruction (presently we have the most to fear from man-made dangers), is abstract reasoning, the ability to think about what will happen next using symbols and language. We don't need to position our senses in a present-time, critical moment to identify and react to a threat or an opportunity; instead, we have the ability to abstract our environment and work out problems in advance, the way a chessboard represents medieval war and a map represents some unknown country.

If you are with me so far, I know you don't need to be told the importance of having a brain. (Not that bodies aren't useful. Most bodies.) Clearly, a majority of humans develop abstract thinking at about the age of twelve, just in time to figure out how to get laid, a fact that we know intuitively but has also been confirmed scientifically by Piaget and a gazillion other psychologists. I am less certain everyone knows what Kohlberg discovered during his review and extension of Piaget's work: he estimated that 30% of people in the US never fully develop abstract reasoning (Kohlberg and Gilligan, 1971). This deficit has consequences more dire than the prospect of these folks going home alone from the Deer Park Tavern after last call. Smart people need to contemplate the mental fitness of the population as a whole, because our survival as a race means negotiating a complex global environment where mostly the danger isn't predators, meteors, or a plague of locusts; the dangerous obstruction is other, stupid people.

One hallmark of abstract thought is drawing conclusions based on authentic, empirical evidence as opposed to getting some cockamamie notion at 3 AM and sharpening the cutlery. In the essay form, it's standard practice for the writer to cite other scholars who gathered experimental evidence in advance of the writing. Prof. Bouree, do that evidence thing you do for the nice people.

It doesn't seem that the formal operations stage is something everyone actually gets to. Even those of us who do get there don't operate in it at all times. Even some cultures, it seems, don't develop it or value it like ours does. Abstract reasoning is simply not universal. (Boeree, 2009)

We have all these folks running around who literally can't do the math. I'm not talking about slack-jawed yokels bounding out of Dogpatch and the mind of Al Capp. I'm talking about accomplished people, college men and women, some of them with enormous power over the rest of us and chests of money! I'm talking about Al Capp, for instance, and others like him who don't have the ability to calculate their own best interest except in concrete, immediate terms. An absolutely telltale indicator of the inability to think abstractly is the failure to recognize that all human life, indeed all life on this planet, is interconnected.

I'm not arguing that calculating one's next move based on the best possible result is easy; I'm saying it is difficult, and many of your  neighbors and countrymen lack cognitively the formal operations to do it. Because we can't actually see, taste, or touch the way our behaviors impact others and vice versa, many folks believe they are secret agents, acting alone, with no accountability to anyone. Capitalists prattle on and on without understanding about individual initiative and how we are in competition with others and that this is a good thing. Their view, while true in a limited and immediate way, lacks understanding of the long-term, the big picture, the ultimate goal of survival of the human species. Don't these libertarians or Ayn Rand objectivists watch Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life (1946)? Well I do, every Christmas, and my favorite part is when George patiently explains to the radically individualist banker the old codger's own self-interest in giving poor people a chance to get out of their slums and poverty.

neighbors and countrymen lack cognitively the formal operations to do it. Because we can't actually see, taste, or touch the way our behaviors impact others and vice versa, many folks believe they are secret agents, acting alone, with no accountability to anyone. Capitalists prattle on and on without understanding about individual initiative and how we are in competition with others and that this is a good thing. Their view, while true in a limited and immediate way, lacks understanding of the long-term, the big picture, the ultimate goal of survival of the human species. Don't these libertarians or Ayn Rand objectivists watch Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life (1946)? Well I do, every Christmas, and my favorite part is when George patiently explains to the radically individualist banker the old codger's own self-interest in giving poor people a chance to get out of their slums and poverty.

Here, you're all businessmen here. Doesn't it make them better citizens? Doesn't it make them better customers? You...you said...What'd you say just a minute ago?...They had to wait and save their money before they even ought to think of a decent home. Wait! Wait for what? Until their children grow up and leave them? Until they're so old and broken-down that they...Do you know how long it takes a working man to save five thousand dollars? Just remember this, Mr. Potter, that this rabble you're talking about...they do most of the working and paying and living and dying in this community.

The whole concept of mass markets and entrepreneurial initiative to access mass markets relies on a large population with the resources to use goods and services. A financial situation like ours in the US, where wealth is concentrated in the hands of the very few, is actually bad for the economy and especially dangerous to those short-sighted few. Writing for Business Insider in an article called "Plutocracy Reborn," Gus Lubin remarks that the last time wealth was so concentrated in the hands of the top 1% of families was in 1928, just before the Great Depression, and conditions today are more dangerous for the superwealthy than they were then. (Lubin, 2010)

Resistence to my premise-- that people with wealth and power very often are too stupid to understand what's good for them-- is great in my country because we are obsessed with money and material things and harbor the absolutely false, untested attribution that people with vast sums are smarter and better than people without it. A recent study indicated that people with money, even if they understood  that they received special breaks and advantages to get it, were most susceptible to the opinion that their wealth confers upon them a special, heavenly grace, and they were less likely to have consideration for others. (Szalavitz) My argument against the mistaken attribution of exceptionalism to the beneficiaries of monetary success is that someone with a very limited ability to apply abstract thought can, nevertheless, acquire a huge fortune. Intelligence is not the prerequisite for wealth.

that they received special breaks and advantages to get it, were most susceptible to the opinion that their wealth confers upon them a special, heavenly grace, and they were less likely to have consideration for others. (Szalavitz) My argument against the mistaken attribution of exceptionalism to the beneficiaries of monetary success is that someone with a very limited ability to apply abstract thought can, nevertheless, acquire a huge fortune. Intelligence is not the prerequisite for wealth.

Genuinely smart people have arranged society such that, in the US at least, survival doesn't require extremely difficult skills like tracking prey for food, finding water, and building shelter. Boy Scouting requires skill; one can achieve financial success with luck. Much of the empty sloganeering of the American Dream comes from Ralph Waldo Emerson, who in Self-Reliance romanticizes the power and glory of the individual, self-made man. Emerson's creation inspires, but ought to include the caveat that everyone benefits immensely from the society in which he or she lives; other people matter. A less quoted philosopher is Don Novello's stand-up character, Father Guido Sarducci. In a routine called "Five-Minute University," he tells us everything we need to know about business boils down to this: "You buy-a something and sell it for-a more." Bill Gates is intelligent enough to realize his enormous fortune came to him partly by accident (Borsook), and he's also sharp enough to know that spending huge sums of money to eliminate disease in Africa and put computers in classrooms in the US benefits all people and himself.

The Koch brothers, Charles G. and David H., inherited the fortune of their father and the second-largest privately held company in the United States. Dad was a chemist who invented a process essential to the refinement of oil into petroleum, which indicates intelligence, and he was also a founding member of the John Birch Society, which indicates an utter lapse in abstract reasoning. His sons continued his work of spending huge sums to promote libertarian ideas, free-market economics, deregulation, and eensy weensy government. They have vociferously opposed universal health care and raising the minimum wage, two ideas that sound economics predicts would save the nation billions of dollars and create wealth (Zieler, Krugman); they also deny the existence of man-made global warming against overwhelming scientific and fact-based opinion. (Mayer) Obviously, it is in their immediate and concretely understood self-interest to reduce their own taxes and block legislation that regulates the oil industry, but they are unbelievably stupid not to anticipate the future catastrophe of tens or hundreds of millions of the poor and uneducated and an even warmer planet, which is already experiencing historic weather extremes--heat, cold, rain, drought, and storms.

Especially when one is born with a monetary advantage, success doesn't require advanced cognitive skills. In fact, the pursuit of money for its own sake shows a pathological deficiency in abstract thought. Money is the ultimate abstraction. The paper it's printed on is nearly worthless; money is a symbol of something else, something with an ever-changing value. Amassing billions and billions of dollars without regard for the planet and one's fellows on it demonstrates an abject failure to distinguish substance from the representation of it. (Pause) "These go to eleven." Nigel Tufnel in Spinal Tap is the best known example of an utter confusion of a symbol for what it represents. This next one is from my experience teaching high school. One of my 16-year-olds was looking at two expensive pull-down maps, one of the United States and one of her home, Pennsylvania. Her wide-eyed reaction was, "I never knew it before: they're the same size!"

The paper it's printed on is nearly worthless; money is a symbol of something else, something with an ever-changing value. Amassing billions and billions of dollars without regard for the planet and one's fellows on it demonstrates an abject failure to distinguish substance from the representation of it. (Pause) "These go to eleven." Nigel Tufnel in Spinal Tap is the best known example of an utter confusion of a symbol for what it represents. This next one is from my experience teaching high school. One of my 16-year-olds was looking at two expensive pull-down maps, one of the United States and one of her home, Pennsylvania. Her wide-eyed reaction was, "I never knew it before: they're the same size!"

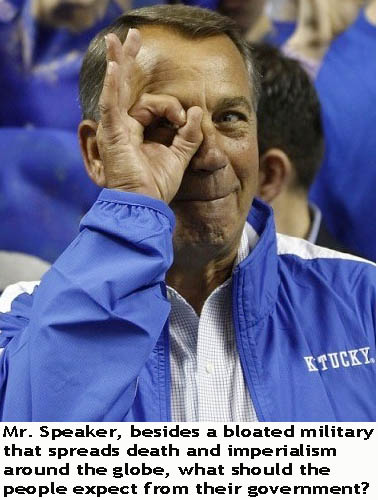

A professor of sociology of my acquaintance was asked by a think tank to express what he expected in the future for America. He predicted doom and gloom. The biggest culprit in his mind was the rise of the belief that any government is intrinsically bad for the citizens and against their self-interest. The nitwits of the so-called Tea Party understand certain catchy slogans (No New Taxes! Big Government Off My Back!), but lack the mental acumen to apply them appropriately.  (Incidentally, they got their own name wrong. Those early patriots were protesting the British failure to tax tea imported from Holland, not the opposite.) Government enacts laws that protect citizens from those with an excess of financial power, and the primary function of government is to redistribute the collective wealth of the nation.

(Incidentally, they got their own name wrong. Those early patriots were protesting the British failure to tax tea imported from Holland, not the opposite.) Government enacts laws that protect citizens from those with an excess of financial power, and the primary function of government is to redistribute the collective wealth of the nation.

When the stock market crashed in 2008, the Tea Party and its minions in Congress resisted higher taxes on the rich, the bailouts of threatened banks and industries, assistance to people whose mortgages were for more than their houses were worth and other government actions that are economically necessary when private investment dries up. They even shut the government down and refused to pay its debts unless these actions included spending cuts, ignoring the failure of similar austerity measures in Europe, and a lowering of the US credit rating that makes money more expensive. Since 2008, the people have actually profited from the payback on the loans it made to banks and business, but job creation remains stagnant. What we needed were huge investments in infrastructure and education that create taxpaying jobholders, improve services, and in the long run reduce deficits. Short-term thinking that flies in the face of evidence gutted support for the poorest working families, reduced public schools to rubble, endangered colleges, and the recession has dragged on for longer than it should have. Smart guys--help the dumb guys.

It's not only the wealthy elite who lack "moral development" (Kohlburg) that we should fear, but also the millions of voters whose understanding is stunted by deficiencies in dealing with the abstract, for our powerful nemesis distracts and misleads the huddled mass who ought to be its natural enemy. An insistence that every word in the Bible is literally true redirects workingclass anger towards narrow "family value" issues, when they ought to be railing against war-mongers and environment defilers. Belief in the imminent return of Son-O'-God leads to an ignorant disregard for long-term, scientifically demonstrated damage to our planet. Rampant global warming denial is based on a misplaced faith that God won't let his people be remembered only from the fossil record when insects take over the archeology and museum-building.

The Word takes on a magical significance that symbolic language does not have, resulting in misunderstanding and harm. If the purpose of the Bible is to give us consolation against a cruel world and show us the best way to relate to our fellow man, why can't it be understood metaphorically,  and why insist that every word means exactly what it says (which is impossible)? The answer must be that many people are completely uncomfortable with symbolism; they must have everything in concrete terms. Ironically, they cease to believe that nature is governed by dependable scientific forces. "Magical thinking" describes a phase of cognition in which objects appear to have no physical continuity and where their every behavior isn't fully covered by the Laws of Physics, and, generally, the human brain outgrows it in infancy.

and why insist that every word means exactly what it says (which is impossible)? The answer must be that many people are completely uncomfortable with symbolism; they must have everything in concrete terms. Ironically, they cease to believe that nature is governed by dependable scientific forces. "Magical thinking" describes a phase of cognition in which objects appear to have no physical continuity and where their every behavior isn't fully covered by the Laws of Physics, and, generally, the human brain outgrows it in infancy.

Other than insisting that a virgin can have a baby, or a man can walk on water, or that a burning bush can talk, evidence of an utter discomfort with the tricky subtleties of language surfaces every time one of Obama's enemies tries to compare his actions to something else. Conservatives demonstrate an utter clumsiness with figures of speech. Thus, on 10/13/13, conservative spokesman Dr. Ben Carson called Obamacare the "worst thing that has happened in this country since slavery," North Carolina state senator Bob Rucho, on 12/15/13, tweets that "Obamacare has done more damage to the USA then (sic) the swords of the Nazis, Soviets & terrorists combined," (yeah, three groups reknowned for their swordplay), and an Idaho state senator, Sherly Nuxoll, emailed to supporters this month (January, 2014) that "insurance companies are creating their own tombs...[m]uch like the Jews boarding the trains to concentration camps." These analogies are reckless, unfeeling, and pitifully clumsy, English language fails that are worst disasters than, um, the Titanic and New Coke combined!

As a Pennsylvanian, I'm always rooting for two-term (!) US senator and erstwhile Presidential candidate Rick Santorum to top everyone in spastic word play, and the sweater-vested little chowderhead never disappoints. "Gay marriage is an issue just like 9-11," he said, in February, 2004, and outstandingly, when Nelson Mandela died, he said on The O'Reilly Factor (12/5/13)

Nelson Mandela stood up against a great injustice and was willing to pay a huge price for that, and that's the reason he is mourned today, because of that struggle that he performed. ..And I would make the argument that we have a great injustice going on right now in this country with an ever increasing size of government that is taking over and controlling people's lives, and Obamacare is front and center in that.

Sometimes people who are weary with politics like to claim that the guys and gals who say and do ridiculous, mind-boggling things like shutting down the government for two weeks to make a quixotic, extremist point about government services, or hand the regulation of our environment over to the worst polluters of it, or compare health care to Apartheid must be accepting bribes from some lobby or corporation. I've always been opposed to conspiracy theories and their flimsy speculations. For one thing, I don't think the Far-Right is skilled enough (abstract wordplay coming) to organize a pack of gum let alone a vast extremist conspiracy. Thinking about the deficiencies of the conservative brain that ignores science, facts, and complex reasoning for the sake of immediate concrete satisfaction is plenty scary enough, but disagree with me and I won't think you're evil, just stupid.

Boeree, C. George. "Jean Piaget and Cognitive Development." Shippensburg University, 2009.

n. pag. Web. 19 Jan. 2014.

Borsook, Paulina. "The Accidental Zillionaire." Wired. 2003. n. pag. Web. 19 Jan 2014.

Gilligan, C. and Lawrence Kohlberg. "The adolescent as a philosopher: The discovery of the self

in a post-conventional world." Daedalus 100(4)(1971): 1054-1087. Print.

Krugman, Paul. "Obamacare's Secret Success." The New York Times. 29 Nov. 2013.

n. pag. Web. 19 Jan. 2014.

Lubin, Gus. "Plutocracy Reborn." Business Insider. 1 Sep. 2010. n pag. Web. 19 Jan. 2014.

Mayer, Jane. "Covert Operations." The New Yorker. 30 Aug. 2010. n pag. Web. 19 Jan. 2014.

Szalavitz, Maia. "Why the rich are less ethical: They see greed as good." Time.

28 Feb. 2012. n. pag. Web. 19 Jan. 2014.

Zeiler, David. "The surprising benefits of raising the minimum wage." Money Morning.

20 Dec. 2013. n. pag. Web. 19 Jan. 2014.

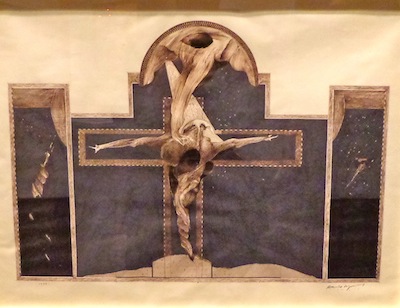

The 19th century geologist Charles Lyell first observed the principle of uniformitarianism in nature: the processes we observe shaping our today-world are the same as those that have always ground mountains into grains of sand. Linda Pompeo’s searching presentation of oil paintings and prints showing at Muse Gallery in May of 2022 strongly suggests that the transformative forces in human experience have been as consistent as gravity for as long as the species has been on the planet. For an artist, certainly, the desire to express the soaring, spiritual power of the human form can’t burn much differently in the breast of a contemporary painter than it did in a sculptor of Samothrace in the year 190 BCE.