Addiction Fiction, What's Your Function?

My interior life is dominated by perceptions I can't communicate. I blame myself for not using the right tools. I write.

Dada rejected the usefulness of reason, which after all had not prevented WWI and, in the century since Hugo Ball’s Cabaret Voltaire, hasn’t prevented the mass murder of millions or convinced voters that Facism is even worse than the high-price of eggs. Society's institutions compile data with advanced instruments of dazzling complexity and highly trained experts interpret those measurements, but the public does its “own research,” guided by podcast influencers whose credentials are celebrity, not academics. Doubtless, the ease of listening and rigor of interpreting text frames the accretion of public opinion, not something with such a flimsy connection to kitchen table politics as written discourse.

By consent of all parties, the undertow of our social dialogue is illiteracy. Schools are casually and often illegally underfunded, while most Americans confess their main source of news is social media. (Tik Tok. Tik Tok. I kept hearing it but had no idea what it meant: I thought MIT or somebody had calculated the planet’s remaining seconds, and the loudspeakers were counting them off to keep everyone moving.) Majority opinion isn’t formed by well-argued reasoning, so elites can stop waving their dissertations. Even fancy-schmancy colleges are jettisoning literature studies–not to mention whole Humanities departments–because reading the classics has no calculable value. Moby Dick has zero likes; you can’t even monetize it. TLDR is such a useful phrase, it was itself too long and had to be shortened.

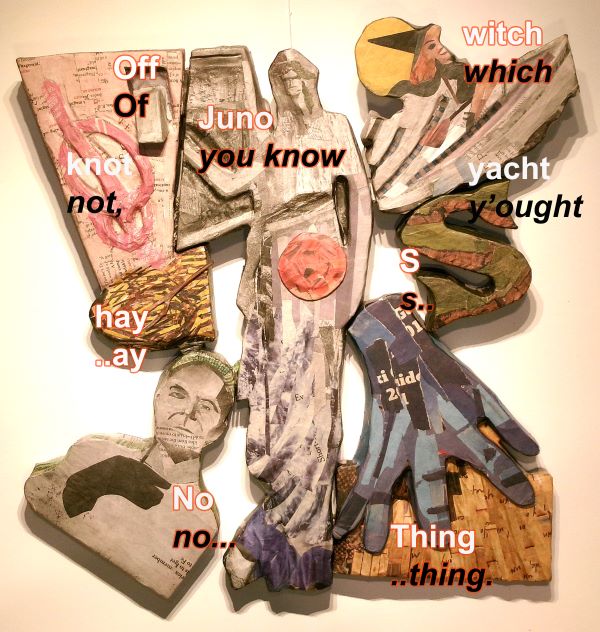

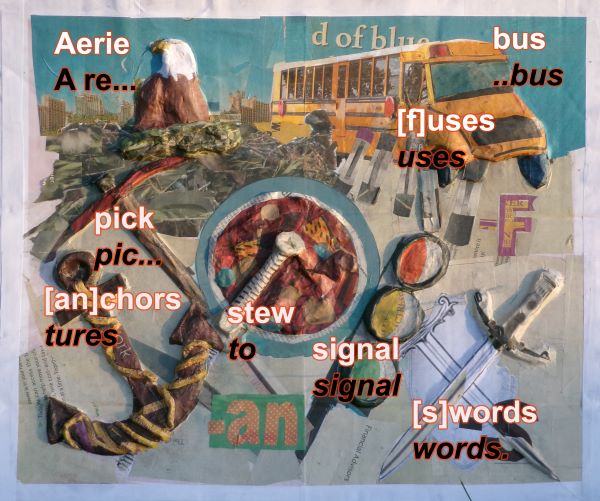

Instead of all that hateful print, rebuses use pictures to convey words and turn communication into a puzzle solution. I didn’t invent the form. In Sumeria 40,000 years ago, they had old guys complaining that nobody reads cuneiform any more. The 60s game show Concentration –the very name was a snide mockery of reason–used rebuses as the final gateway between contestants and valuable prizes. A gibberish of 3D images reproduced in brilliant print advertising, the paper, paste, and glue rebuses I’ve made convey phonetically some inscrutable witticism or another that is no more a product of reason than all the circled nouns in a Word Find. We don’t need a well-reasoned essay to form our opinions; we did our own research on YouTube. Jump over that pesky wordle hurdle. Pictures and placards are sufficient to express the width and depth of our ideas. We only use words to lie to ourselves.

So long as it doesn’t exceed 60 characters in a meta og:description the American public will accept any lie that endorses their Fabulous Las Vegas Shopping Spree. The public’s compulsion for buying cars and consumer goods has been represented analogously in some of the best fictions of the second half of the last century to descriptions of alcohol and chemical addiction. The public's compulsion to buy whatever they're selling is like a morphine habit and must be obeyed, even if it kills them. Led by the lies the oligarchy leaves swirling around on media platforms built with unthinkable amounts of capital, angry wage earners vote to keep their own oppressors first in line or in office. Under the zombie-like thrall of the American Dream (at least we call it what it is), they believe every citizen, through hard work and gumption, can get a house in the suburbs and a car. No Substitutions. The losers deserve what they get. They must not have worked hard enough.

As described in Naked Lunch and Junky, the “straight world” of William S. Burrough’s 50s presages our bleak present, an infinite con, pushing familiar cants like hard work and morality to make people easier to control, and dangling shiny merchandise to distract them from what’s really going on: humiliation, torture, and endless tiers of corruption. Burrough’s response is in the form of satire, obscenely vile and violent like its subject, not an essay explaining how to live, with the writer behaving like a Holy Man, pitching his elixir of life on the midway. “Are we never to be free of this grey-beard loon lurking on every mountain top in Tibet. ‘I’ve been waiting for you, my son.’ and he make with a silo full of corn. ‘Life is a school where every pupil must learn a different lesson. And now I will unlock my Word Hoard.’ ‘I do fear it much.’”

Substantively, Naked Lunch is a diary of junk addiction. My edition of the book includes all of the accompanying notes written by the author since he finished it in 1957 and after the court battles permitting it to be distributed by U.S. Post. Burroughs flatly says the book speaks from the viewpoint of a heroin addict; specifically, the tale of physical, sexual, and political tortures is written from life and not fiction. Junky, the author’s chronicle of his fifteen-year habit, contains descriptions of the horrors– hallucinations and dementia brought on by either alcohol sickness or heroin withdrawal. Nothing short of torture matches the terrors of delirium, the skin crawling and the mind hallucinating death in physical form. Burroughs was surprised how, during his sickness and delirium, he had managed to take the notes that became Naked Lunch. The work is testimony, he points out in an accompanying note, not a fictional contrivance. Whether Burroughs intends his addiction and the tortures inflicted upon the addict as metaphors for consumer society and its degradation of the workweek’s outcasts, he certainly uses the language of capitalism to describe heroin trafficking:

"The pyramid of junk, one level eating the level below (it is no accident that junk higher-ups are always fat and the addict on the street is always thin)...Junk is the mold of monopoly and possession. The addict needs more and more junk to maintain human form."

Laws against narcotics serve a practical purpose: to create jobs and revenue for the enforcers of those laws and increase the profitability of narcotics to benefit the dealers. There will always be people who want to produce it, Burroughs says. There will always be someone who sells it. The only part of the equation in short supply is the addict. Morphine addicts, whether they, like Burroughs in Junky, are trying to score H in a hot neighborhood, or like millions of straight citizens who got theirs legally in the form of Oxycodone, don't form an intent to buy their daily dose. The cells of the body are in control, not the will. The public needs to understand the system is an economic one, not a story about vampires and fiends, which is a con told to the taxpayer to get their funding support. Remember, the junky needs the drug to maintain human form. We recognize each other by our addictions.

Penalties against dealing junk are no more effective in curtailing the addict’s behavior than consumer protection laws are at inhibiting monstrously large pharmaceutical companies from creating and profiting from addicts. The lie is an open secret, high sounding moral platitudes being just a con to hoodwink taxpayers into supporting laws intended to create a high-priced black market, corrupt law enforcement agents, and agencies with a rubber siphon tube shoved into a tank full of tax dollars.

Drug addicts are a knowing subculture, created by the illegality of the drugs, with its own lingo, its own network of connections, pigeons, and ghosts. Because the rest of the population demonizes them and legislates to deprive them of their liberty, the underground forms a resigned opposition to straight culture. Seeing it from the outside, through the x-ray glasses of the junkies who aren’t addicted to stupid jobs, stupid things, and the company of stupefied people, the hipster is in a position to recognize the twinned banality and brutality that comes in the same package as America’s inextinguishable hunger for material novelties.

While Burroughs was there, New Orleans made addiction against the law and put junkies with needle marks into jail or barbaric “rehab” facilities, each of which forced immediate abstention instead of a tapering off and induced the worst horrors of the disease. Burroughs describes a sudden police push to round up the junkies as giving the new law a nice send off, a blue-ribbon ceremony. Wards of men experiencing mortal terror were all in a day’s work, making a whole brutal police bureaucracy appear to be necessary to the public’s safety.

Inhumane treatment of addicts amounts to medically sanctioned torture. Burroughs testifies that when he was forced off heroin by incarceration or mandatory hospitalization, the means of getting the addict off junk other than cutting him off completely was available, but rarely used. Burroughs knew a doctor who prescribed an effective antihistamine when an addict was junk sick, but the doctors in County hadn’t heard of it. Withdrawal from heroin is feeling agonizingly uncomfortable in your own skin. You know John Lennon’s song “Cold Turkey”? Withdrawal is worse than listening to that.

Society has what sounds like a perfectly logical explanation for administering Gestapo-style tortures. Conned into the idea that one must earn the right to live, decent, church-going folks have the deep conviction that the derelict and broken deserve inhuman treatment, a calculation that reveals humanity is equivalent to wealth, not a human birthright at all but something you have to leave a deposit on and which can be revoked.

Naked Lunch’s Dr. Benway casually performs vivisections, amputations, and hideous anal assaults on his patients, proclaiming the dead or disfigured remains as “all in a day’s work.” Like capital punishment, another state-sanctioned crime against humanity that makes Burroughs come on like Johnny Revelator, inhumane medical treatment puts the lie to every dictatorial policy enacted by the Establishment in the name of public health. Burroughs didn’t live to see the further disintegration of the medical profession into the equivalent of a doctorin' shopping mall that doesn’t give care–It’s a medical product now, so go caveat emptor yourself. Plus, you have to belong to the insurance version of Costco to afford even inadequate treatment. Given that the Hippocratic oath and capitalism are strictly incompatible, guess which had to go?

Charles Bukowski’s description of his time in a charity ward tells about a hospital staff just as casual about administering death as Burrough's Dr. Benway. After fifteen years of heavy drinking, one day Bukowski is spitting out gobs of blood. A van carries him in a rack arrangement along with several other destitute bums to the best care flat broke can buy. During the ride, he's struggling to keep the blood in his mouth so he doesn’t drip on anyone stacked under him.

In the hospital ward, Bukowski lies in his own blood and piss overnight. Next day, moving him from one ward to another, the nurse and orderly complain when the patient becomes faint and unable to support himself. Despite his pleading that he can’t help it, they complain about the trouble he is causing. “He’s no fun! He fell right over.” They have to lift him up, find a new vein, stick the tube in again. What a pain! “And look–he’s bleeding on me!”

A clerk tells Bukowski he doesn’t qualify for a transfusion because he never donated blood. They would have let him bleed to death except someone found out he had a long-lost, solidly upright father who had an account with a blood bank in Georgia.

Rather than live in Levittown, working at the plant like an eyeless, sexless drone to deserve the privilege of respectability and the abstract glow of the Dream, Charles Bukowski matter of factly chooses the concrete necessities of alcoholism. He is defeated, but so what? The game was the pointless pursuit of a blue ribbon which fades to brown, anyway. “Our raving starts quite quietly while we are staring down at the hair of a rug–wondering what the shit went wrong when they blew up the trolley full of jelly beans with the poster of Popeye the Sailor stuck on the side.”

Ideologies are either oppressive or useless to save the oppressed. In the short piece ”Politics is Like Trying to Screw a Cat in the Ass," Bukowski disdains the cause of justice. “Are there good guys and bad guys? Some that always lie, some that never lie? Are there good governments and bad governments? No, there are only bad governments and worse governments…” In a poem, he expresses sympathy for the bums shivering in the cold out on the road. Everywhere they go, everything is locked. This is Democracy in America.

Democracy is about having two sides and the strongest imposes the rules of the game on the weak. Freedom of choice doesn’t liberate us to do hateful jobs for abusive employers; we don’t have Democracy to make people equal. We have it so we are free to spend our money on whatever we want–so long as somebody gets rich–and to get laws enacted making sure other bums can’t steal our shit. Predatory confidence men write laws to enshrine the rights of monolithic monopolies and to make corporate bastions unassailable, and they don’t care which bum’s name the majority is afraid of gets typed in the orders.

Having too much self-respect to work the angles himself, Bukowski doesn’t try to con anyone that he’s an artist– a writer with causes or ideas. He’s a hack because “wouldn’t you?” What’s the actual damn use of words, except maybe to sell a 1000 of them and buy maybe a gallon of port? Sometimes Bukowski doesn’t capitalize words at the start of a sentence or leaves out periods at the end, not out of some stylistic perquisite of James Joyce or that annoying e.e. cummings, but particularly because literary forms and pretensions are more horseshit and what you get for the trouble isn’t worth it.

"We’ve had these centuries of knowledge and culture and discoveries to work with," Bukowski writes, "the libraries are fat and crawling and overcrowded with books; great paintings sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars; medical science is transplanting the human heart; you can’t tell a madman from a sane one upon the streets, and suddenly we find our lives, again, in the hands of idiots, the bombs may never drop; the bombs might drop, eeny, meeny miney, mo…"

David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (1996) contains a much-discussed, symbolic conflation of addiction and consumer compulsions, a film cartridge called only The Entertainment. In the way of classic science fiction, one has no problem suspending disbelief over whether such an invention could exist, since, on the scales of the plot, it isn’t so much a thing as a emblem, as in the way Flubber represents Professor Fred MacMurry’s ricocheting mind, absent from reality. Wallace’s invention is no less possible than Jeff Goldblum’s twin, technosteel phone booths that had him sharing a party line with a fly.

Glimpsed even briefly, The Entertainment captivates the viewer so completely, they literally cannot turn away. They keep watching, ignoring all other bodily needs, until they die. I’m reminded of the killing joke in a Monty Python sketch that caused anyone who stumbled into it to die laughing helplessly. The Japanese movie Ringu, released two years after Infinite Jest but based on a story published five years before it, is about a cursed video that, instead of being compulsively consumed by the viewer, leaps off the screen and eats them. In Ringu, once you’ve seen the cursed film, you can only be saved if you recommend it to others, which is a striking stipulation coming as it does more than a decade ahead of the Like button.

Many characters are addicted to many different drugs in Infinite Jest and the mystery is why the fix of drugs like the fix of fossil fuels is irresistible to the point of death. Warnings, common sense, and vows of any sort are of no use against the narrowing of consciousness to a pinpoint focus. Burroughs calls it the junky stare, being content to gaze at the end of your shoe for eight hours; Billie Holiday said she could tell when she was “cured” of addiction because she couldn’t watch television anymore. Alternatively, the novel’s heavy footnoting, references to an encyclopedic range of texts, only some of them spurious, suggests the story may be understood not only as the narrative of many lives hemmed in by unsustainable compulsions, but also as it connects to an omniscient academic overworld, a godly plane where an individual man’s character is fixed and meaning is possible. The reader begins to pick out which of the footnotes are frauds, and eventually recognizes even the glosses are desperate to make rational sense of it all.

The cross connections between various texts are microscopically detailed, yet the simple answer to why people do what they do remains obscure. The title of the novel is a reference to Hamlet's speech "Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio, a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy.” The play of words, the nested phrases within phrases our syntax makes possible, distinguish language from rote. Every word contains both meaning and connotation, the traces of its whole history that are unteachable and yet accumulate in the listener's flesh. All of it for nothing, a few laughs and witticisms to divert us while waiting for the grave. Hamlet matches any character in literature for excuse-making word play, the rebuses of image and phonemes that yield puzzle solutions, but don’t solve his dilemma or kick him into gear. “I’ve got big boy problems!” They don’t prevent the slaughter one can clearly make out in the distance. None of his speeches contains what we would call an intent later fulfilled– only doubt, hurt, and obfuscation.

Hal Incandenza, arguably Infinite Jest's protagonist but more accurately its junction box, is presented as having an encyclopedic mind and an addiction to marijuana, which offers a retreat from his crippling anxiety in public: he doesn’t feel emotions or evidence any feelings at all and has difficulty expressing himself. His manner is off-putting, although his teachers believe he could be a genius. Hal’s written statements near the book’s end suggest he is becoming more comfortable with his emotional life, but after a chemical contamination, his body synthesizes a drug that limits his speech to a monstrous, terrifying grate. Burroughs said it: You can’t beat the kick inside. Ultimately, speech fails, and body is all.

His name is Hal, like the murderous ghost in the machine from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), a computer guided by logic whose every act of consciousness can be mapped out and connected to a physical cause, and who for no reason becomes homicidal. We understand immediately that Hal has no inner life: he’s all output; the calculations are wordless. Why can’t we accept that Intention in humans is also a figment? At the very least, we should realize we don’t use consciousness to deliberate but to rationalize. We don’t know the math by which a guy calculates he can have another shot of morphine without getting hooked. We don’t even know where he keeps his calculator.

A masterpiece of addiction fiction, Malcom Lowry’s Under the Volcano predates Naked Lunch by a decade and communicates the topic very differently. The same imagery and signs read in a different order change the rebus’s solution. Lowry presents the Consul’s alcoholism the way Geoffrey Firmin himself reads it: as the curse of God. All the Gods. The genius of Lowry’s book is how like a lava flow swallowing everything in its path, Under the Volcano's consciousness contains glosses to a cosmological pantheon–the Tree of Life in Kabbalah, the Zohar, the Vedas, Aztec mythology, the alchemy notes of Paracelsus and every other book, probably, Lowry ever read. But, like the footnotes in Infinite Jest, the mountains of texts only feign authority and pretend relevance. Their bluster rings hollow. The Consul (who is as close to a stand-in for his author as one will find in literature) gives his drunkenness a cosmic significance, a personal, but also heroic, fate spelled out like a picture puzzle in the volcanic peaks of Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuat, the Infernal Machine at the fair, skeleton candies celebrating the Day of the Dead, a pariah dog, or a horse with the numeral 7 branded on its rump. To cast one’s misery as the mark of God is another of the ways the addiction rationalizes itself in our own voice, to keep the routine of self-deception going.

The last time he sees them before dying stupidly, the Consul snarls at his wife and his brother that they are trying to help a doomed Faust. Damnation is his glory not his shame! Staggering out of the cantina, he wonders, “Do they think I’m serious?” Behind the infinite jesting and puzzling is pure terror. Does he not love life enough to forgive himself or those who have hurt him? The solution is much simpler and needs no story vampiric or epic to convey. He is afraid to stop drinking and the drink will kill him, but knowing this is irrelevant to quitting.

In the New Orleans jailhouse, the cops were doing their cop routine, grilling William S. Burroughs, and the sympathetic one took over from the threatening one to ask, “Why do you do it, Bill? Why do you use heroin?”

“I use it to get out of bed.”

My addiction is to the human form.

--Drew Zimmerman, November 2024