The Canon of Roland

Partial text from Stories of Gods and Heroes (1960) illustrated by Art Seiden.

We can’t know how a book enters the vocabulary of all books, influencing how other books are understood and burnishing the connotations of every word it touches. The addition of The Canon of Roland to the library of humanity is problematic, whether it was discovered in manuscript form, bound in hard covers, or preserved in a digital file. Its difficulty is not in the narrative’s style or plot but the form: a list of books the narrator has read across his lifetime with frequent notations describing their influence on him. If that’s a plot, it is of the tedious variety, where, with much handwringing, nothing happens. To the author of the list, the books on it are merely titles, some of them among the greatest works in Literature, where all books exist abstractly in the totality of their meaning, in fact, like items on a list, but this fellow claims to have read them and experienced them, left to right, word after word, and The Canon of Roland tells the story.

Bluntly expressed, if The Canon of Roland is a book of fiction, then its unusual metaphysics are nothing more than a plot device, like the djinn in A 1000 and One Arabian Nights or Wells’ time machine. On the contrary, the teller of Roland’s story presents a credible case that he is not a narrative voice in a work of fiction, but the writer and originator of an annotated bibliography representing the accumulation over time of an understanding of his human dimension, a writer who inhabits physical space with measurable distances between the objects in it. If we reject Roland as a character in a book of fiction, we must accept him as a material human experiencing time–that pure abstraction necessary to tell any story but completely irrational when applied to the finite library of every human word, so vast as history itself but invariable as Plato’s forms.

Imagination concocts some truly horrible creatures from this list of particular tales and the man who claims to have been put together from them like Frankenstein’s monster. A fictionalized biography of a platypus and a lavishly illustrated collection of Western myths are the first entries in Roland’s canon and the only two that don’t identify a particular publication. The omission, attributed to having read them at the very limits of memory, shrouds the pair in the mist of legend. The platypus suggests to the young reader his own developing sense of himself, that he is an unlikely creature made of incompatible parts, an animal as singular as the order of monotremes, mammals who do not have nipples and hatch from eggs. A notation declares the platypus the reader’s spirit animal, but the marginal note like the others on the list could be written from the perspective of an older man recalling how his younger self reacted. We might consider he exaggerates the auspiciousness of the first book he read.

Every title is portentous in fiction, and so the course through a timeline of titles seems fraught with purpose. While an ordinary list presents component parts unorganized, Roland’s list is an itinerary with a beginning and end. As a reader, he crosses from one to another literary icon like they were stepping stones, and the account of his reading merges with the timelessness of the print. Depending on how they are read, the marginal accounts tell a picaresque story in which the author himself is a fictional character, encountering friendly and tragic books, avuncular books and books whose absurd confabulations become the permanent traffic circles and “No Outlet” signs on the roadways of his thinking.

If The Canon of Roland is a story about a lifelong reader, the second book on the list, a splendidly illustrated book of myths and legends, tries our patience with an obvious attempt at puerile metafiction. The Greek, Roman, and Norse gods inhabit the earliest stories in the catalogue, and the seven-year-old child, we learn, commits to memory all their names, elemental powers, and passions. He draws with pencils and crayons on notebook pages lined in blue the monsters slain by Theseus, Perseus, and Jason. Perhaps reading so soon as he is able narratives near to the essential uses of story focuses too much on the role of form in them, which works best when it is invisible. Only poor writers lacking real content insist on making the nature of narrative fiction a subject, so a reader of The Canon of Roland, coming upon Cronos eating his young on page one, has reason to groan, anticipating what strained nonsense happens next.

A marginal note says he chose the name of the legendary paladin of Charlemagne, Roland, he of the unbreakable sword, because the precious book of world myths and legends he owned had a striking picture of the slayer of Saracens printed across two pages of text. He can summon that fearsome illustration to mind until the end of his life, which, it is useful to mention, he represents with the last book on the list, Middlemarch, a multiple-volume masterpiece of well-fed and self-important gentlefolk, huffing and puffing smalltown gossip in absolutely the ideal country shire to retire to. The vanity of writing a narrative connecting Prometheus to a checkbook drama set in the English Midlands so exasperates that giving away the ending is more of a friendly warning than an ill-mannered spoiler.

Real life, as literary fictions describe it, is a series of random encounters on paths chosen for either no reason or the wrong one, an arrangement that is contrary to the clockworks of fiction. (Like a list!) The Canon of Roland provides a narrative, fulfilling a destiny. To know the meaning of one’s own life is being on the road to Thebes with the wreckage of a tripartite monster behind and a strangely familiar driver ahead, who refuses to yield. We assign temporality to memories, generating a narrative that can never represent the present moment in which actual living occurs, the same present moment everywhere and in every direction and conventionally symbolized by a single point.

Roland’s narrator is certain of his origins and definite about his conclusions. We especially like the part where he moves! He must be a fiction.

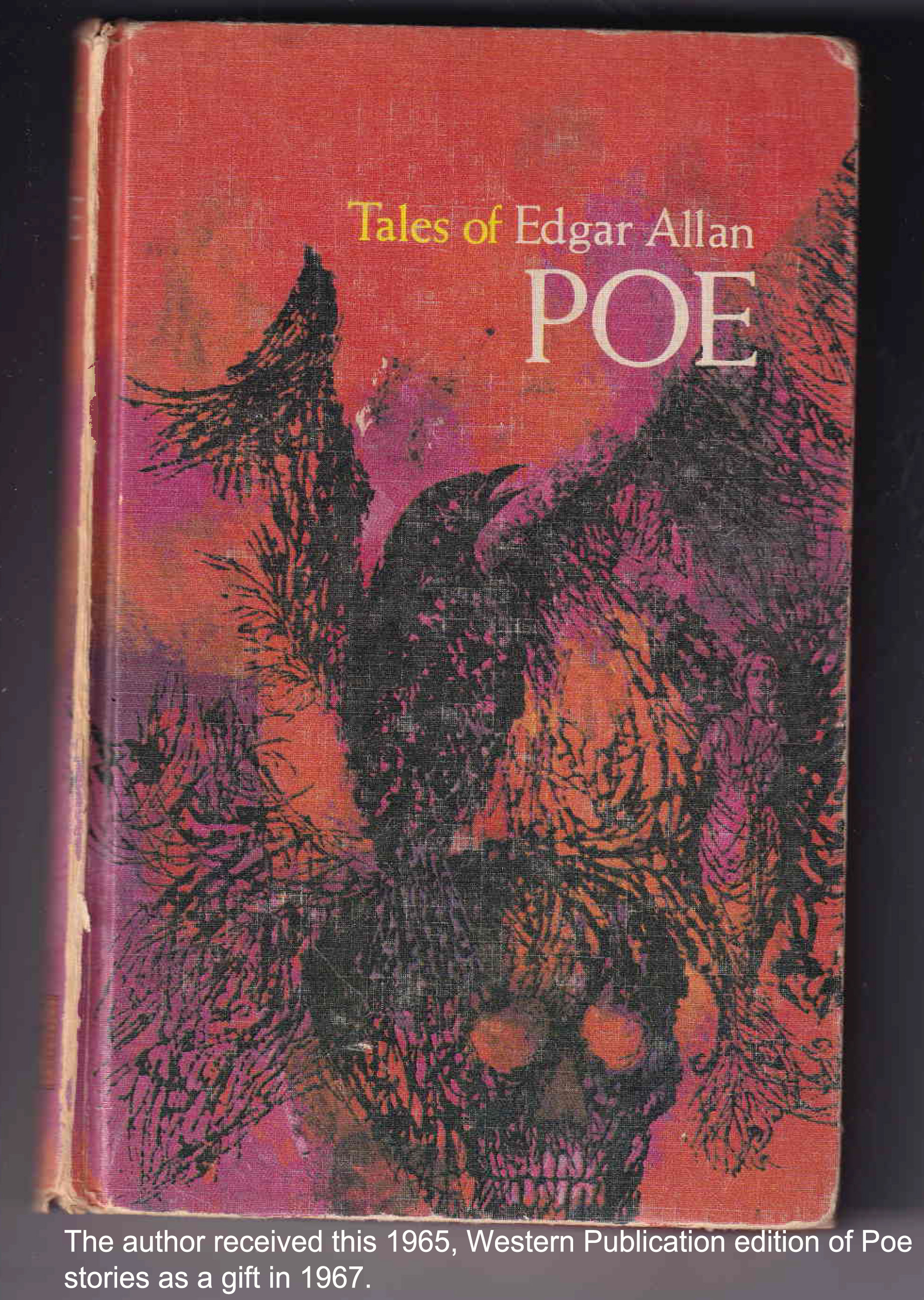

Also when he is seven, Roland receives as a gift Tales of Edgar Allan Poe. The stories were represented to him as having supernatural subjects and more of the fantastic monsters in which myth abounds. Roland finds not one, single instance of occult forces, but he has the insight that ordinary human rationalization and compulsion cultivate monstrosities exceeding even the fabulous creatures in mythology. He writes in the margins of his reading list,

From Poe I learned what madness truly is, an interior life completely incompatible with the experience of other people. Listening to the explanation of Montresor for brick and mortaring his friend in a catacombs,—a personal insult not worth going into but demanding mortal revenge—made me realize crazy describes everyone’s narrative of their life. Our stream-of-consciousness version of the tangible world we exist in has no resemblance to the world outside it. Yet, the drunken alcoholic who gouges out his cat’s eye and buries an ax in his wife’s head believes these horrors to be ‘nothing more than an ordinary succession of very natural causes and effects.’

an interior life completely incompatible with the experience of other people. Listening to the explanation of Montresor for brick and mortaring his friend in a catacombs,—a personal insult not worth going into but demanding mortal revenge—made me realize crazy describes everyone’s narrative of their life. Our stream-of-consciousness version of the tangible world we exist in has no resemblance to the world outside it. Yet, the drunken alcoholic who gouges out his cat’s eye and buries an ax in his wife’s head believes these horrors to be ‘nothing more than an ordinary succession of very natural causes and effects.’

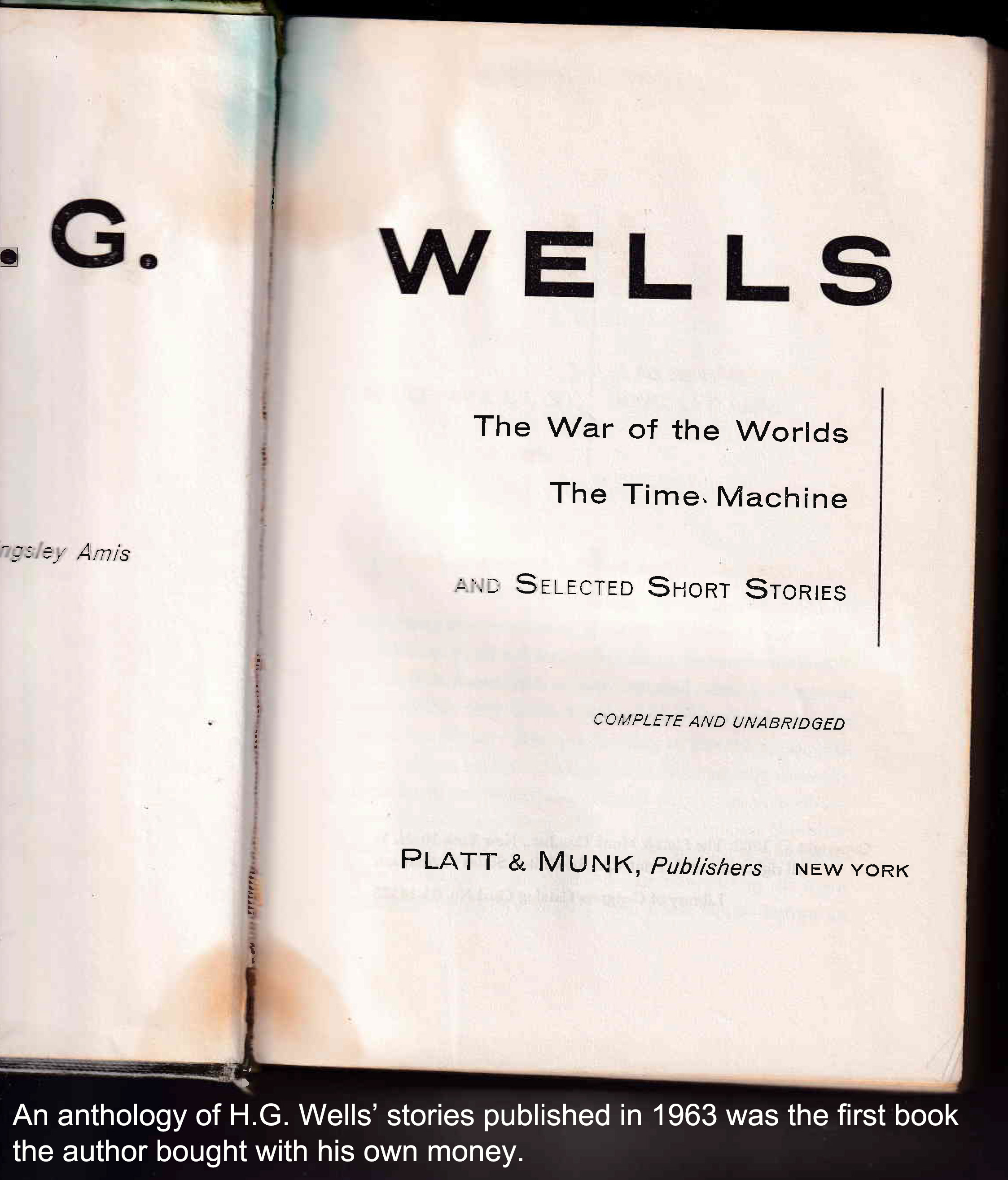

In the same year he is introduced to Poe, the first book Roland buys for himself is an anthology of H. G. Wells stories. He is drawn to Wells because he anticipates futuristic machines; he expects monsters from outer space or from a mad scientist’s arrogance, but as with Poe, the book doesn’t contain any phenomena that can’t be explained with reason and ordinary causes. Wells’ stories are less thrilling, feverish dreams than parables extolling human virtues in completely recognizable situations. “The guy has a time machine, and instead of checking out dinosaurs firsthand, he goes to a bleached out future, no more fascinating than a high school with exclusive cliques: pretty, empty-headed Eloi at one lunch table, and Morlocks, the out-all-night losers and jocks, at another.”

Similarly, Wells never shows any Martians, green or polka-dotted, and  War of the Worlds turns out to be a caution that the microscopic world and the humblest germs in creation are more marvelous than creatures from outer space. Instead of monsters out of a Catholic bestiary, we see not-that-scary interplanetary shipping tubes, tripods, and cameras, the gentle result of Wells’ humanist suspicion of machinery and somewhat less than awesome.

War of the Worlds turns out to be a caution that the microscopic world and the humblest germs in creation are more marvelous than creatures from outer space. Instead of monsters out of a Catholic bestiary, we see not-that-scary interplanetary shipping tubes, tripods, and cameras, the gentle result of Wells’ humanist suspicion of machinery and somewhat less than awesome.

Roland also sees through the conceit of mad science in The Invisible Man, which, he writes,

..is no more what I would expect science fiction to be than the tale of Midas with its magic alchemy. Vague references to chemistry and optics are no more or less credible than the elaborate backstory of Heracles and the Shirt of Nessus, which includes the Hydra AND a centaur. Whether the agent of transformation comes from a laboratory or not, if you drink it, it’s a potion. Moreover, the guy in the book doesn’t do ANY of the things you are supposed to do if you’re invisible.

Instead of giving his hero the enviable power to walk through a girls’ locker room undetected, invisibility in Wells’ story refers to the interior consciousness of man, visible to no one. Usually, consciousness is equated with reason or the soul, but in Wells’ metaphor, the anchor to our human form is our corporeal self, our flesh and blood, not the ghost in the machine for which no empirical evidence exists. The hero wishes to be free of his physical form, but his reason disappears with his flesh and blood! Wells’ fable denounces the idea that mind is the requisite for selfhood; instead, a bodiless invisible man is bereft of reason, his humanity faded to nothing. Roland anticipates a different theme, but he admits the meaning he finds.

The Seven Chinese Brothers, Light in the Forest, The Wonderful Flight to the Mushroom Planet,

Star Surgeon. Random selections from an elementary school library are Roland’s next stepping stones. A modest man in a tweed suit comes to Earth from a distant galaxy to grab a chicken to go. A geekish, four-fingered alien with an empathic protein blob on his shoulder struggles to fit in at a star base medical college. We hope Roland will enjoy these boyhood sci-fi adventures without commenting on their form, and we are disappointed. He describes how each story helped forge the lamps and manacles he will live by.

A book about seven identical Chinese brothers who are each invincible to one kind of capital punishment or another is, to Roland, not so much a fully formed story but a story-churning device. He argues that the attribute of Brother One that causes all the trouble, swallowing the ocean, plainly puts the tale in the same category as creation myths. The other brothers all have a single identifying attribute as well: invulnerability to a particular means of dying.

The book is only a story because of the repetition of what is essentially the same event: a poor man is condemned to death six times and defeats death six times. Different categories of death are superfluous; invulnerability to spearpoints or scimitars is the same thing, and why should being burned alive be any different? From three wishes to three bears, repetition is the oldest motif in storytelling. So, the fable is about one thing, not seven, and that one thing, so far as I can see, must be the endless cycle of God’s rebirth. But whose god? Certainly not the Chinese.

A minor children’s story that effects mystery by invoking images of yellow men in pillbox hats and braids with their hands hidden in their smocks, The Seven Chinese Brothers is a significant book to Roland because it and the next book he reads help form his opinion that not only does the affectation of having more than one occasion of the same event in any narrative violate the monism of Parmenides, his teaching that creation is a single whole and multiplicity is an illusion, but it also fails to be true to life, where time's passage cannot be understood empirically and where "we name the days of the week after dead gods as a caustic reminder of their arbitrariness." Thus, the basic problem with The Canon of Roland: its narrator restates literature’s most distinguishing feature, that every book originates from the same alphabet, speaking in the same voice and from the only time. For this reason, when we quote what a book says, it says it in the present tense. Intolerably, the narrative showing how Roland's understanding of this axiom coalesces implies his exception to it. The reader is expected to suspend disbelief and accept chronic Roland as the colloquial happening dude.

A lurid true crime story, the next book we encounter on the list (and again, the idea of next on a list is as ridiculous as thinking the nutmeg comes ahead of the nuts in a recipe) contrasts harshly with the more staid, literary titles. The Boston Strangler describes a string of about a dozen murders of elderly women in 1960s Boston, the city-wide panic they caused, and the massive manhunt to capture the killer. Roland provides a detailed account of how a twelve-year-old acquired such inappropriate material. His favorite uncle was an avid reader who also had copies of Lolita and Psychopathia Sexualis in his bookcase. An idle fellow, he lived on various sinecures, like building inspector or postmaster, do-nothing patronage jobs handed out by his friends at the VFW post, evidently because a very nasty conviction on a morals charge limited his employment opportunities. Whenever Roland’s family visits, they find Uncle reading in a Barcalounger, wearing a sleeveless t-shirt, pajama bottoms, and slippers.

Shirtless, he had a white, sunken chest and an old man’s pectorals that drooped like unbaked croissants from each nipple. He liked to challenge me with novelty puzzles of interlocking steel loops, and I would show I didn’t understand what the puzzle was asking by trying to force the pieces apart instead of solving the knots. I was on Uncle’s lap when he told me about the Boston Strangler’s reign of terror. The perverse subject was fascinating—another human monster!—and he sent me home with the book as a gift. Clearly, he was inviting me to share illicit subject matter that made me complicit with his degenerate lifestyle. Wasn’t he? I took the book, whatever its significance, and devoured the sensational story in a few days.

Roland’s parents don’t object, although they ought to be wary. On the other hand, wouldn’t you rather your child learn about sexual pathology from a dictionary than in the back alley?

As with The Seven Chinese Brothers, the presentation of a single horror as occurring in different locations with different victims struck Roland as a device peculiar to the form of fiction. The impact of the murders was always the same, conveyed by the connotations of words that were common to each crime scene, regardless of the different bed, bathroom, or elderly victim on the floor. Roland notices how the repetition of the same murder morphed a pathetically unexceptional handyman into a monster who crawled out of the dark, collective unconscious of Catholic Boston. The fictionalization of human activity–its causes and effects at the molecular level and spread across the entire Bay Area–crushes the details and measurable data to dust because they aren’t necessary to convey pure horror. “The accounts describe the crime scene and leave out the lurid details. Everyone leaves out the lurid details, because the two words don’t appear in any other context, and we can imagine them without help. Moreover, what the hell is ‘desecration of the corpse’? Isn’t anything the living do to a corpse a desecration? The visceral impact of the phrase, not a precise meaning, is all that matters.”

Roland recalls reaching the place in the story where the explanation for the psychology of a psychopath was supposed to go, and while there were descriptions of various irregularities in the man’s history, how could anyone do the math that added up to homicidal necrophilia?

One time in my early childhood, my father accommodated my interest in how an electric motor worked by taking off the housing of Mom’s mixer and showing me the wires, tiny metal brushes, and magnets, but he didn’t know the physics. Or there weren’t any! Not on that afternoon, anyway. Disappointed, I burst into tears, and my well-meaning dad shrugged helplessly over his crybaby son and took a quick exit, probably to get a drink. No physics governs human motivation. Cry yourself dry, you’ll never find an answer to why anyone does anything.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is another instance of a single person existing in multiple bodies or across identical settings, and another time Roland the reader looks forward to digging into a monster melodrama and instead gets a lesson on our divided and contradictory humanity. The doctor’s duality is presented as either all evil or all good and his inability to balance the two abstractions in a more tangible, statistically bound set of behaviors accounts for all the trouble. So far as how the author concocted a story from the basic human condition—or at least the slang version—any two characters in conflict have drama built into them. "Vladimir and Estragon wait. I’m breathless!" Do we find comfort in stories that personify pure evil because a narrative must resolve itself and in fiction events follow a predictable pattern? Horror and murder without the justification—the shape—of a recognizable story are literally unthinkable.

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn, The Once and Future King. Roland’s career as a reader threads familiar paths. Some of the titles alone on a printed page have such well established meanings, Roland admits he understands them in their received version without adding any insights of his own.

Hasn’t everyone read Huckleberry Finn before they touch it? Do Injun Joe or Buck do a single thing to revise our expectations of non-Whites? No, because the engine of Twain’s stories depends on standardized parts. Apart from Hemingway and his safari get-up with the elephant gun, has any author maintained such a trademark appearance as goddam Mark Twain in that goddam white suit, looking like the plantation owner whose Southern culture he panders to? Even his pen name is a commercial calculation, calling himself after a standard of measure peculiar to the American frontier and guaranteeing the reader nothing that will run the river boat aground.

Still a teenager, Roland perceives an unlikely kinship in the work of Franz Kafka and James Thurber, two writers who are never mentioned in the same breath. Their short stories are the exception to Roland’s typical schoolroom reading, which had themes that were played like cards over kitchen tabletops. Perhaps, their connection had to do with his introduction to them. Recalling to his son the last time he had read anything of substance, Roland’s father sent him to retrieve a moldy cardboard box in the crawlspace under the house. The teen, hoping to get a glimpse of the man before he was burdened with children and a growing beer belly, excitedly unpacked from the wobbly package elements of his father’s sense of humor and rejection of ordinary routine. A cardboard box, shared by college texts and issues of Argosy and Wink, was the only remains of Dad’s intention to get a degree in English before he dropped out to join the Navy.

Thurber and Kafka are the antidote to the cornsilky adventures of Twain and Huck. Their subject is the amputation of human possibility, not its boyhood promise. Thurber’s modern man is humiliated by stopping at the garage to service his auto, because holding an umbrella over a newly coiffed poodle subjects him to the contempt of the mechanic. He daydreams about being a war hero or a dashing surgeon, but his wife knows the truth: he forgets his overshoes. Every opportunity for adventure is false in Thurber: the dam didn’t break, the bed didn’t fall, and hearsay prevailed. “I heard him say to hell with the flag, too!”

In “The Dog That Bit People,” a foul-tempered animal controls a human household with his biting and insistence on his own way. They give over much of their lives to Muggs. For instance, as a gesture of apology to the mail and delivery men the foul-tempered Airedale has attacked, Mom gives out fruitcakes every Christmas. This year the list is up to over fifty names. In Thurber, life means compromising to the point of erasure, with romance posing the worst danger of all, as his comic essay Is Sex Necessary? points out.

The henpecked husbands in Thurber retreat from action willfully, accepting  helplessness to control even the family pet. In Kafka, the law, the castle, and the courts appear to impose Mr. K’s limitations from the outside. “But existence is all of a piece and there is no outside. Creation is perfect, situated in one dimension not several, but the factory-fresh version comes with a built-in, this-can’t-be-right feeling.” The received description of Kafka’s unfinished (yet continually released in identical editions) novels was advocated by Max Brod who controlled the manuscripts posthumously. The Czech writer, Brod says, presages the Nazis and protests authoritarianism. In Roland’s view, the short stories express a human dilemma more complex and much more funny.

helplessness to control even the family pet. In Kafka, the law, the castle, and the courts appear to impose Mr. K’s limitations from the outside. “But existence is all of a piece and there is no outside. Creation is perfect, situated in one dimension not several, but the factory-fresh version comes with a built-in, this-can’t-be-right feeling.” The received description of Kafka’s unfinished (yet continually released in identical editions) novels was advocated by Max Brod who controlled the manuscripts posthumously. The Czech writer, Brod says, presages the Nazis and protests authoritarianism. In Roland’s view, the short stories express a human dilemma more complex and much more funny.

Thurber would recognize the narrator in Kafka’s “Investigations of a Dog,” whose distillation of the mystery of life is “Where does the food come from?” He’s blind to the existence of humans entirely. Every dog knows, scratch the ground and look up: the food appears. But from where? “The Burrow” is about a molelike animal, pushing through the ground with his forehead, building an invader-proof labyrinth. So obsessed is he with satisfying himself of the construction’s impregnability, he puts himself in mortal danger to observe predators walking past the burrow’s fake entrance. He goes outside to apprehend his creation the way others do, like a person with OCDs checking to see if the door is locked, over and over.

Roland begins by complaining about Kafka’s best known story.

The giant bug in “Metamorphosis” could have finally provided a decent monster story, but NO. Gregor’s deadpan acceptance of his fate is hilarious, scurrying on the ceiling, trying to fake the good son like crazy. Life goes on despite being vermin, and so forth. What’s telling is that his manager shows up at the family flat within two hours of Gregor not appearing at his desk. Considering the clerk’s unimportance in the vast bureaucracy that rises up around the denizens of Kafka’s nightmare dreamscape, why does the boss leave the office and rush to see what’s wrong? Because the story is one of those dreams where everything is broken, Gregor is the dream, and the dream is also broken. His foot melts into the linoleum. The clock bogs down. Your family rents out your room.

So far in his winding course through the library of mankind’s view of itself and its distortions, Roland learns the shape of the human form is elastic and, while each of us chooses our nature, we generally choose the weakest version of the animal, the one with the narrowest range, or possibly, the only mammal without nipples. For all of its imagination and adventure, the myths of the Greeks are filled with pointless repetitions: the eagle who comes every day to devour Prometheus’ liver; the voice of the monster who visits Psyche every night; the single labor of Heracles, repeated nine times in makework assignments straight out of the WPA: clean the stable, fetch the apples, build the first post office in Pyrrhus. Going back to the seven Chinese brothers and the Boston serial killer, most of the stories Roland encounters favor routine over unlimited possibility. Roland identifies a prominent feature of the form of humanity’s stories that makes the individual content of any of them beside the point.

On the verge of his senior year of high school, Roland’s campaign of independent scholarship takes him to War and Peace. At the time of Roland’s secondary schooling, Tolstoy’s doorstop of a book is frequently mentioned by secret non-readers as the ultimate endurance test for anyone who still clings to the idea that the deepest expression of human ideals is found in literature. The length of it is the only aspect of Tolstoy’s novel that earns so much as a mention; nevertheless, Roland reads the story of Napoleon's capture of and retreat from Moscow with admiration. “How can we still have wars when Tolstoy spells out the folly of them so explicitly and convincingly?” he asks naively.

Roland is still too inexperienced to realize the image of Pierre trudging through the snow in deserted Moscow, looking for a place–any place–to make a stand, conforms to the relationship between flesh and bone humans and the abstractions of language. In the perpetual struggle to confirm one’s worth, no one knows where to stand. “The Napoleonic Wars” is a convenient way of talking about an infinite number of minute adjustments to the human experience, and equally abstract are “the defense of Moscow” or Pierre’s duty to it. We understand what people are getting at when they talk patriotically about “country,” but we have no idea in any single moment of our lives what such a vast idea means to us now. Roland writes

‘Our connection to the language of literature is like this picture.’ But that’s a white page. ‘No, it’s Pierre in a snow storm.’ Where’s Pierre, then? 'A polar bear ate him.’ Even Roland, the paladin of Charlemagne, even he, who swears to cover his sovereign’s retreat to the death, is a creature of legend not life. Anyone can tell you, the only unbreakable sword is the one the pen is mightier than.

Hamlet, Labyrinths, As I Lay Dying, Invisible Man. By the time he is in his 20s, Roland drinks habitually and begins to notice an accompanying internal dialogue that compulsively comments on shameful or misfiring events in his past. As his drinking at inappropriate hours throughout the day leads to recklessness and humiliating detection by others, the ceaseless excuse-making for either faux pas or shattering outrage only increases, all of it in the form of an internal dialogue with which he can only negotiate a ceasefire for minutes at a time. Drinking until he passes out gives longer respite, but the strain on his body and personal life is great.

Hours in the day he had always spent reading were the ones he now commits to heavy drinking. From childhood, the depth of his reading requires concentration, and his busy, wandering mind needs a swat now and then to stay on point. Boozy, he was even more likely to lose the sense of a sentence somewhere along its length. Thus, he read Dante’s Divine Comedy as if he were confined to the special Hell reserved for well-meaning friends of unpublished writers, who are sentenced to never read anything all the way through—for Eternity. Whan folk longen to goon on pilgrimages, Roland goes part way to Canterbury, sits under an oak, and doesn’t remember what happens next. Nothing wrong about that: Chaucer himself never finished.

One book that emerges from Roland’s drinking period mostly intact is of the true crime variety, of which he read many. Compulsion is based on a celebrated killing for the sake of killing. A couple of Jewish college boys in affluent North Chicago read Nietzsche, and what they get from Zarathustra is that they had to prove their superiority by whacking a snotty neighborhood kid on the head with a 4-inch pipe and stuffing his body in a culvert. Postwar America, still seeking an answer for how the Nazis obliterated one of Europe's great cultures, believed a philosophical treatise that called for a superman was the cause of a murder by advantaged teenagers. That the crime was loaded with signs of pedophilic rage and other named pathologies occurred to no one. One day, Americans will hold their own Nazi rallies, and the reason why will still be obscure, but Roland firmly doubts literature has anything to do with it.

Other than haunting Roland with the knowledge of the banality of evil, true crime-based fictions illustrate with images of murder scenes the constant self-recrimination and resentment he rehearses in his consciousness. “Are the images in my mind pictures? I can’t even tell. Maybe one’s a 3 X 5 card that says ‘human offal’ on it and another one says ‘bloody ligature.’ Words or pictures, they harrow me.” His pulpier reading choices also supply the voice of the compulsive narrative in Roland’s head. The lawyer who saves the joy-killing college boys from the death penalty is the master of courtroom theatrics, none other than Clarence Darrow himself. His cigar growing inches of ash at the end, his fingers crooked in his suspenders, he argues to a bodiless jury (the same that condemned Mr. K in The Trial) why his client must be excused for decades of reckless harm and ordinary embarrassments. “His painstaking accumulation of guilt—and, let’s be clear, resentment—contains instances from 40 years ago that no one remembers but himself, and his memories are weaker than a second pot of coffee, poured through the same grounds as the first.”

Nausea, The Stranger, Catch-22, Under the Volcano. In evaluating the contention that The Canon of Roland gives a history of encounters with literature, we don’t suggest the books on the itinerary, his list of annotated titles, are the cause of his behavior. More likely, books with familiar themes draw Roland to them, and books that resonated with his natural understanding are his best remembered. After he finally stops drinking and stays sober, Roland responds to a passage in Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano, articulating an insight that helped him quit. Minutes before he is violently killed, finally realizing his own death sentence for crimes unnamed, the Consul, drunk as always, angrily berates his wife and half-brother for trying to save a doomed man, cursed by all the gods, even the local Aztec ones. Leaving the cantina, he says to himself. “Do they think I’m serious?”

The Consul is not cursed. His rant is only skunk spray, a misdirection to conceal the true and only cause for his estrangement from all things: he won’t stop drinking. Roland gives up ritual intoxication, but develops other obsessive routines. Acting as his own consul, he devises endless summations to the jurors of his mind, justifying a resentment with obscure origins. Memory sorts through a particular dossier so many times that Roland only rehearses the contents; eventually he can’t even remember the file's name. Roland reads in Sartre that the moral guilt he feels is a fraud and can be brushed aside with a finger snap. In The Stranger, random intersections produce effects for which no cause or intent exist and every narrative is false.

Maybe if I were ugly like Sartre or handsome like Camus I’d have the guts to leave my obsession with guilt and punishment on the roadside. If I were Yossarian, maybe I would have the courage to say, ‘Why should I fly a mission to bomb Germans? Germans aren’t trying to kill me.’

I don’t know why I can’t shake it off. Do I think I’m serious? The trouble is, I have loads of self-awareness, but I don’t listen to me.

Remembrance of Things Past. Proust’s five volumes, reconstructing settings from his youth, begin with the fragrance of a Madeleine cookie; alternately, without any empirical provocation, Roland compulsively calls to mind the scripted version of regretted events and half-formed pictures that go all the way back to childhood humiliations. Over the years, the same birdsongs represent the broadest characterizations, unlike Proust’s recollections, which are filled with details like the damask pattern on the drapes. Roland wants to ignore the rationalizations in his head, realizing his compulsions have a voice that talks in his own, but he is troubled. If it isn’t in the spiteful words he uses to describe himself, where resides his true and absolute core? Where is the part baked into the sinews and muscle memory? Where is the part he never ignores, because he can’t?

Kant says products of the mind are more legitimate than contingent sensory impressions. Information we gain from our senses is conditionally flawed, while the compulsive routines Roland has indexed to unpleasant occasions in his mind have no physical counterpoint and are perfect as jewels. What he can never know is why these rehearsals of effacements in the past produce observable cries and shudders; nevertheless, a regular theme of his descent into angry depression, scribbled in the margin next to Swann’s Way, is how his youthful joy over mastering literature was replaced with disillusionment over the importance of letters in the first place.

From the first books I read, I recognized the various conceits of stories that take the interminable sameness of day-to-day existence and reinvent it as 1001 Arabian Nights. Individual language acquisition has a phase called mind reading, in which the new speaker recognizes the words of other people can be contrary to fact; moreover, the evidence of other minds in speech indicate they are having different internal experiences than our own. These realizations are necessary to work the pieces of language that imply imaginary displacements of future and past or convey the complex relationships between I, me, and yours. 'Someone help! I can’t get my predicate nominatives in line!'

I acquired this understanding early. I saw how language invented 30,000 years ago to give directions to Karakung, the valley of geese, was quite useful and could be empirically confirmed. Even so, a map is not the place it describes. We use the same abstractions constantly, until distance, time, character, history, by their constant drumming, make us forget they have no substance at all.

give directions to Karakung, the valley of geese, was quite useful and could be empirically confirmed. Even so, a map is not the place it describes. We use the same abstractions constantly, until distance, time, character, history, by their constant drumming, make us forget they have no substance at all.

Pride was my downfall, for sure. In our culture, the first thing that comes to mind when a prodigy steps forward is how their skills can be turned into a monetized career. I never cared about money, but I sure as hell didn’t want to work. I thought my talent would be rewarded like sinking baskets or fixing cars. My confusion was natural. We have books all over the place, so I thought someone had to be writing and reading them all. I ought to have known better.

My own insights into the mechanisms of fiction told me they are irrelevant to meat and potatoes. I realized when I wrote my fourth grade compositions how the words I used were renditions of the birdsong I heard in books, nothing else. I wasn’t alone: no one composes their speech! We chirp and cheep the sounds of cardinals on sentry. The people don’t need to read. They don’t even read directions! You can’t underestimate the influence of written language. We don’t read books, but we often make meaningful gestures at the stacks.

Other than the Bible, Joyce’s Ulysses is the least read and most referred to book in print, but Roland waded into its fanciful version of characters’ internal dialogue. Virginia Woolfe’s assay of private speech in Mrs. Dalloway more authentically resembles stream-of-consciousness than Joyce’s, which is less likely than the famed Wanamaker pipe organ accompanying the Cocoa Puffs jingle. To Joyce, the entire written output of humanity files through in our thoughts exactly as if the words were our own. Ulysses coordinates the physical space of Dublin with corresponding words and phrases existing simultaneously around the fires of Hellenic storytellers. For Roland, who describes his own speech as birdsong coming unbidden from nowhere, Joyce’s conceit makes sense.

On the Road, Naked Lunch, V. As Roland’s depression deepens and his compulsive mantra of mixed regret and anger consumes more of his reason, he encounters the ugly corollary to Ulysses’ expression of a shared experience of the Western World’s literature: the automatic language of a shared culture of degradation in Burrough’s Naked Lunch. For Burroughs language is a virus, invading the DNA of our human construct with expressions of cruelty and gangsterism that are no more remarkable to us than Mrs. Dalloway’s thinking about her flower arrangements, and we can’t deconstruct them. The devaluation of human life is our blueprint, not the heroes of Homeric stories.

Like the marginalia attached to The Canon of Roland that purport to describe his development since childhood, the first person notes accompanying Naked Lunch identify the source of Burroughs’ fury: America’s hypocritical institution of capital punishment. Organized murder by electric chair or firing range as a punishment for violating God’s prohibition against murder is an absurd paradox made possible only by the sophism of language. Dr. Benway’s vivisections and torturous experiments to see if applied agony might actually improve the life of the common man generally kill the patient, but it’s “all in a day's work” in the name of science.

We use the language of reason to justify dropping the “miracle of science” on hundreds of thousands of Japanese. Big numbers work best in these matters since anything larger than eight is incomprehensible and doesn’t even register as actual people. Our shared life in Naked Lunch’s Interzone is that of a hollowed out junky, either helplessly joining the continuous buying frenzy of straight society or hip to the national addiction for death toys and other consumer goods, and making a morphine exit, God-willing. Our language is the patter of con men. Dedication to science is a con. The dignity of man is a con. The admiration of James Joyce’s Ulysses is undoubtedly a con.

The Magic Mountain, The Recognitions, JR. Toward the end of his list, Roland favors long novels of a thousand pages at least. Their recursive features remind him of The Seven Chinese Brothers or Jack the Ripper. Across a decade in the rarified air of a mountain sanitarium (no more or less real than Kafka’s castle), The Magic Mountain tells how a man’s view of a proper life transforms. For Roland, long gone is the temptation to sift through the chapters to see what Thomas Mann recommends, the way he approached Tolstoy in high school. His observation disregards any wisdom the story arranges itself to espouse.

The book magically illustrates Zeno’s Fallacy of the Heap in real time. Page after page, the words accumulate a letter at a time, an index of meaning, if not the real thing. Perhaps the reader follows the transformation of Hans Castorp as entropic: from advocating a hyper-organized state to a bland relativism. Or maybe the character actors he meets no more allegorize systems of governance than the Cowardly Lion and the Tin Man. It doesn’t matter; it’s not that kind of puzzle. Zeno asks: if Hans Slothrop enters the sanitarium as Hans ^One and each moment means nothing, and the next moment means nothing more than the last, at what point does any moment add up to his transformation into Hans ^Two?

Zeno, pupil of Parmenides, asserts that since the Universe is one thing, it is indivisible. Challengers will point out the appearance of a truth contrary to sense indicates the fallacy arises from the syntax of language. Zeno replies that the idea of a fixed Hans that transforms in discrete phases to another Hans is also an artifact of language; a critique contrary to sense is required.

Unlike Mann’s linear progression, the puzzle form in Gaddis’ novels is circular: a labyrinth. The story passes like a baton from one to another character, and the reader has the sense, if the tumblers were to align—that is, if all the characters had the same information—dozens of frustrated subplots would be resolved. Roland attempts to plot the occasions in The Recognitions where a character with a pressing question randomly enters the same space as a character who possesses the secret, but neither are aware of the conjunction. “I plotted a map of characters’ appearances and labeled the intersections, hoping to reveal a pentagram or figure 8. Someone did the same thing with the correspondences between Ulysses and The Odyssey. All I got was a smudged Pick-Up Sticks.”

Roland has made the point elsewhere that fiction has story-generating gadgets to get around the dreary sameness of mundanity. “Gaddis’ long and winding construction creates the very lifelike feature of serially reaching and then forgetting a unifying key for his catacombs. His maze continually bring us where we have been before. Whatever means the opposite of recognitions is the novel’s occult title.”

Technically the last titles in The Canon of Roland are David Foster Wallace's final novels, and the obviously incompatible Middlemarch. (The list’s marginalia mention one more book at the bottom of the last page.) Infinite Jest conflates addiction with consumer culture just as Naked Lunch does. Wallace's language is not so violent. His method is to convey deformities of the literal and figurative variety in the same reasonable tone as the human insect is rationalized by Kafka.

The uselessness of language except to misrepresent experience is a theme of Infinite Jest: a central character has enlightened intuitions he is desperate to share, but a drug experiment causes his speech to emerge from consciousness as barking gibberish. The mechanical and literal device in Infinite Jest that serves the same generic purpose as Wells’ time machine or the Helmet of invisibility worn by Perseus is a deadly consumer product in the developmental stage. Mad science creates Infinite Jest, a video made from a diabolical codex that is so compulsively watchable, one glimpse causes a viewer to completely ignore their biological necessities—they watch TV until they die.

The recognition of his own compulsions and expressions of the futility of language in the outrageous inventions of Infinite Jest makes the book one of Roland’s favorites, but his encounter with the posthumously published Pale King is on a different footing—not reader, but editor. Wallace’s death was before the novel’s final form had been shaped. In the foreword, which is as much a part of the official book as its last chapter, the publisher’s editor insists the resulting work conforms to the author’s intentions. As usual, Roland dismisses intention as a figment superfluous to action.

That intention cannot be detected empirically ought to be enough to leave it out of any discussion about the finished product, but our own experience shows the tenuous connection between mentalisms and tangible evidence. In a recent news story, a guy in B___ County shot and killed his 80-year-old father who was sitting in the bathtub. Then, he beheaded him on a video he posted to social media. His intent was to force the US government to meet his demands: close US borders, expel all foreigners and progressives, and fire all government employees. The defense argued, therefore, he hadn’t committed murder because his intention was political action.

Guess what I’m thinking.

Roland becomes obsessed with the idea that The Pale King isn’t put together correctly from the pieces that remained when its author died. In its published form, the novel contains vignettes of marginal people who live in their own strange worlds created from incompatible parts, like the platypus in Roland’s iconography. A woman nails a lattice of hubcaps to the exterior of her house because “that madman Jack Benny is using radio waves to control people’s brains.” In the trailer park where the same woman’s granddaughter girds herself against bullies and predators, one kid and his mom have an unexplained exposure to massive amounts of asbestos fibers that ravage their lungs in just a few days. Someone else somehow ingests ground glass.

Roland observes:

Living in an incomprehensible torrent of images and idealogues, transient people build their own psychic burrows, away from the clamor, and imagine their invisibility to any number of dangerous predators on the outside. They imagine monsters and how they will look dead. As in Thurber or Kafka, in an infinite universe, the telescope swings around on people, and they focus on a tiny part of a vastly more complex and confusing whole.

Perhaps Roland is aware of the irony when he begins to devote more and more of his day to revising the chapters of The Pale King, his plan to restore them to their “natural order,” referring to the antique aesthetic requiring literature to be edifying. Using as its setting the vast, incomprehensible bureaucracy of the IRS, The Pale King forcefully iterates the endless, compulsive routines to which we become shackled, hidden from both the natural world and ordinary human discourse. Deprived of mindless repetitions to distract us, motionless in a formless environment, emptied of a single feature that can be plotted with an itinerary, our jittery boredom is intolerable. Roland fanatically believes that, if he can arrange The Pale King’s material optimally, it will show how to shed the compulsive self-belittling and inreasingly violent outbursts that have become the pastimes of his private life. Like a song stuck in the head, his mad compulsion has an accompanying ditty:![]()

Whenever his project of arranging the pieces of a book into every mathematically possible sequence frustrates, Roland turns to reading and rereading the 224,000 words of Middlemarch. He came to the book through misdirection: he thought George Eliot was someone else. Living in a lightless, domed, country hamlet of his own construction, Roland reads the stories of persons of every class pursuing ordinary goals like sensible land reforms and raising money for a new hospital. The book’s very specific rendition of the sensible private speech of clergymen, second cousins to the aristocracy, and spendthrifts forced to settle accounts diverts Roland from his own interiority, full of the rationalizations of Poe’s narrator in “The Tell-Tale Heart,” who interrogates himself: Why do you call me mad?

I know the end I foresee from my unendurable torment may appear unreasonable to whomever finds the evidence of it, but I can’t imagine another solution. I discovered the means in an account of a notoriously gruesome murder, of which a photo of a naked woman divided in two is the most horrifying legacy. It turns out severing the body was the killer’s most sensible act. The best way to walk through a hotel lobby with a freshly murdered woman is to make her corpse fit into a pair of suitcases. He dumped the expertly bisected halves of the body in an empty lot, and took the suitcases with him.

I wonder what he still needed them for.

I can’t outrun the blank stare on that mutilated face with the hideous grin and I’ve stopped wondering why. Most of the time I ideate my only escape, ‘ideate’ being the medical term for hatching a certain kind of scheme. Sensible as the first five volumes of Middlemarch are, is its resolution any more reasonable or less violently terminal than the one I plan for myself? After all its intricate, piece-by-piece assembly, delicate as a ship in a bottle, Middlemarch is Dorothea’s prison and she escapes it, walks away like it was a shaggy dog story. The whole stupid fancy pours through the hole she makes like grains of sand emptying an hourglass of its hoard of time.

The canon finishes with Middlemarch, last in a list of books, nothing else; however, that title carries a gloss to another novel not on the "official" reading list, but surpassing all the others in its expression of man’s existence.  Like Roland, who lies at the end of a dock of the bay with a heavy suitcase tied to each wrist, the narrator on the last page of the footnoted adventure also clings to a piece of wood, floating between himself and the rest of Creation. Footnotes to the canon tend to function like the ones in David Foster Wallaces’ epic tales, which is to ironically suggest an exterior to the story and an omniscient overmind, an amusing conceit, but of course no sentence in any book ever written has information privileged above the whole, footnotes included.

Like Roland, who lies at the end of a dock of the bay with a heavy suitcase tied to each wrist, the narrator on the last page of the footnoted adventure also clings to a piece of wood, floating between himself and the rest of Creation. Footnotes to the canon tend to function like the ones in David Foster Wallaces’ epic tales, which is to ironically suggest an exterior to the story and an omniscient overmind, an amusing conceit, but of course no sentence in any book ever written has information privileged above the whole, footnotes included.

The book referred to in Roland's marginal note follows a doomed voyage around the globe, and its wisdom comes from the last book added to the biblical canon: Ecclesiastes. The message is that the true form of God is unknowable and the absolute form of our lives even more so. The author of Moby Dick sits in the crow's nest above the known world, sifting through encyclopedic entries on cetology, historical shipping records, the Almanac and the Old Testament to pin down the nature of the dragon in his adventure. A hundred years before postmodern writers had invented all kinds of "metafictions" trying to construct a vantage from which may be observed the distinctly human compulsion to make stories out of the heaped up, same old, same old, Melville broke open the cosmic egg. Though it contains every speculation about creation man has ever made, it has no answer to God’s rebuke of Job: “Were you there when I placed leviathan in the oceans?” And not a single supporting text casts the giant creature as a monster, even with its terrible whiteness.

Emerson, who was a member of Melville’s circle, wrote of being impressed in literature by the appearance that all books are written in the same voice, by the same “omniscient gentleman.” Melville glimpses his presence behind the voice of Literature. In a passage of Moby Dick, the Pequod’s first mate, Starbuck, regretting that he has gone along with Ahab’s blasphemous pursuit of revenge against a mute beast, innocent creature of God, describes the whale's divine aspect as a "demigorgon," a mispronunciation of demiurge, the Gnostic name for the false god of biblical creation who made a flawed world populated with flawed men.

The oneness of God is perfect, which leads to the paradox of his imperfect vision: God makes man in order to see in our endless stories his own reflection; perfection must create what it doesn't have—an outside—to appease its pride of creation.

And so we imagine Roland from his list of books that encompass the finest expressions of humanity, clinging to a drifting plank on the verge of the horizon, the edge of eternity. The reader's voice merges with the words of his story, part of the whole that spawned all of the books ever written. Roland has a weighted suitcase tied to both wrists and contemplates pushing them into the water, finally ending his own tortured narrative. He projected the present in a past moment, planned it and imagined it. He calculates with the calm steady reasoning of the man in Poe who kills an elder and buries his heart under the floorboards because he can’t stand another day with the old man’s strabismus. “I have no choice! My situation is insufferable and demands I put an end to it the only way I know!"

Meanwhile, off the record as it were, an indescribable process that may be called taking an inventory at the molecular level of protein shows what Roland does next in spite of his declarations and terminating vow. Connected by glosses and footnotes, his story is part of the vast, timeless Library of Humanity, and in Moby Dick the end of the story and the beginning happen in the same moment, pasted across the horizon. I bet you can see it from here: a newly formed man, perfect in all his members and ready to join (or finish) a voyage round the globe, invites us to call him by the name he has just then amended to a blank page.

Drew Zimmerman, © 2025