Rejecting Liberal Kitsch in Art

My neighborhood has a Vinyls problem. Affluent suburbanites here spend thousands of dollars to erect Easter Island-scale monuments of kitsch. Walk in any direction and one sees holy days shrines to every icon of commercial Christmas animation–and Santa Claus, whose lineage is somewhat longer: Thomas Nast, not Rankin/Bass.

I wonder about the tiny people who own these lawns, live in these houses, who turn on the mighty fans that keep their vinyl idols upright and the spotlights that illuminate them all night long. I imagine they have some vestigial longing to celebrate humankind and a vague idea that the best way to do it is with art. This, of course, is where they flounder. Hailing the passing Range Rovers and Cayennes with creepily mute and chemical memories of trademarked, mid-60s television characters does not convey actual human experience. Is it art, does it even count as sculpture, some crappy, Jumbo-Sized inflatable that supplants fellow-feeling with a shared nostalgia for Clarice the reindeer, whose gin-blossoming sire I am prohibited from mentioning, or else pay a royalty to Gene Autry? If they weren’t so trivial, they wouldn’t need to be two stories tall to hijack my interest.

According to social media, I have 500 artist friends, and I am sure almost all of them would agree with me that the banal themes and icky materials of blow-up lawn novelties disqualify them as worthwhile art. The only thing that recommends them is they make the work of Jeff Koons unnecessary. The folks who pump air into these deflated-of-meaning monuments, using secret technology that will not become the subject of next-century, alien envoy speculation, lack the imagination to spend their money on work by an original, creative sculptor, celebrating organic human existence. As their horizons are so narrow, they communicate to the passing public with a ready-made, commercial television iconography because it is easy and instantly recognizable, or in the words of Frank Zappa, “a little bit cheesy but nicely displayed.”

So why do so many artists hook their own work to some publicly circulated, easy to understand, cause or another? I think disingenuous presenting one’s work as promoting a progressive idea in order to create an importance for the painting or sculpture other than what the work materially is and the viewer’s experience of it. I’m hoping the reason artists fall into this error is they don’t understand some indelible particulars of presentation. The use of artistic images polemically or to promote an ideology isn’t art; it’s advertising. And because emblems of a political perspective are pre-sold, their emotional impact carefully calibrated to create a particular rhetorical effect, the object is instantly kitsch: schmaltzy and predictable. Cute, but not beautiful. Appropriating images and ideas, which like coins are soiled with the patina of daily use, diminishes the thrill of encountering the unknown. I wonder if artists who frame the results of their own human journey as so much liberal kitsch aren’t lacking in confidence about their own powers of creation or the significance of their personal experience, such that they try to make their work important by linking it to some platitude about which no controversy–or curiosity–exists.

A disclaimer by me that my tastes are personal, reflective of the limited opportunities afforded to one who has never ventured out-of-body, goes without saying like the art I despise. But that’s why I think reading these words (and thank you sincerely for that!) or checking out the visual art I’ve put together or the work of any other artistic original is worthwhile. The only art that matters to me expresses the individual experience of its creator, what I always call the hand of the artist. Bored, I walk past work that illustrates the torture of Prometheus, Jesus on the Cross, the plight of a particular target of oppression, the oncoming Apocalypse, or the zero risk of a vinyl Frosty melting on my 66-degree, climate-changed lawn in mid-Atlantic December. What does any of that have to do with my experience, alone with my consciousness, trying to separate cant and custom, what’s for sale and what’s worth keeping, myth and lies from existence?

I know the world has very concrete problems with concrete solutions. My reaction to that is to vote and be kind. Expressing a liberal political position in an artwork, however exceptional the medium and skilled the technique, communicates a social cause, not the alienation of the individual trying to explain his or her own experience without any reliable signs and symbols. Slogans belong on billboards for Light Beer. If the artist can convey the message of their art with a single sentence, I’m saying that it is a vastly depleted art, lacking courage, or it wouldn’t suppress the essential human impulse beneath the pantomimes and rote exhortations.

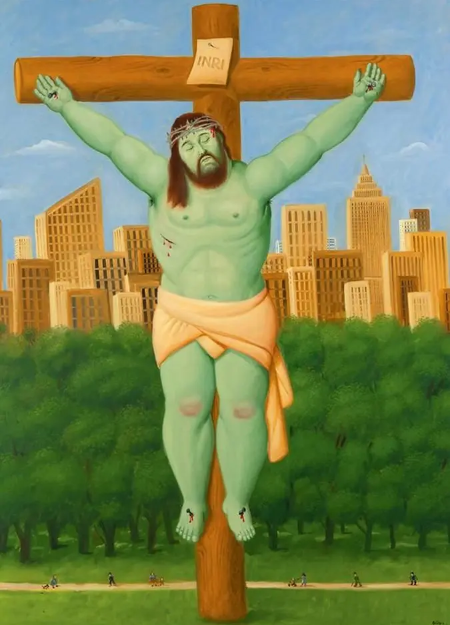

Consider Botero’s Crucifixion (2011). We cannot regard it as anything other than ironic.  This is not the use of Christ as a symbol of suffering to redeem mankind. Certainly the effect of Botero’s portrayals of the bourgeoisie as Macy’s Day floats is completely known by him to be incongruent with worshipfulness. This is Christ as kitsch, propped up in Central Park like candy floss on a stick, not as important as the towering city in the background, but equal to the dogs on leashes one meets, walking the path. In his oeuvre, Botero ironically employs the traditions of portrait painting to present the self-important people who historically were its customers. In his Crucifixion, the artist turns from directly characterizing the well-to-do to representing the supreme symbol of their religion as a Pokemon card. Alternately, when I think of the vapid crucifixion presaged in Salvadar Dali’s Last Supper (1955), hanging in the National Gallery, the failure of the work is its unabashed sentiment and the artist’s pandering imitation of faith. Surrealism as a compositional style becomes what it was destined to be: a fantasy art idiom suited to dorm room posters.

This is not the use of Christ as a symbol of suffering to redeem mankind. Certainly the effect of Botero’s portrayals of the bourgeoisie as Macy’s Day floats is completely known by him to be incongruent with worshipfulness. This is Christ as kitsch, propped up in Central Park like candy floss on a stick, not as important as the towering city in the background, but equal to the dogs on leashes one meets, walking the path. In his oeuvre, Botero ironically employs the traditions of portrait painting to present the self-important people who historically were its customers. In his Crucifixion, the artist turns from directly characterizing the well-to-do to representing the supreme symbol of their religion as a Pokemon card. Alternately, when I think of the vapid crucifixion presaged in Salvadar Dali’s Last Supper (1955), hanging in the National Gallery, the failure of the work is its unabashed sentiment and the artist’s pandering imitation of faith. Surrealism as a compositional style becomes what it was destined to be: a fantasy art idiom suited to dorm room posters.

Using a ready-made visual language, well-worn metaphors for justice, fear, awe, and suffering, the artist may as well by using emojis. Yes, yes, we know everything sucks and will continue to suck. But you–how are you getting along? Equally boring to me is art that ingratiates itself by being obviously aligned to a one-time radical and now passé art movement: Surrealism and also Pop, Conceptualism, Impressionism, Abstract Expressionism, and Futurism. Some of these have manifestos, and how Fascist is that? The group names of the rest weren’t even categories the artists applied to their own art: they were essentially “friend groups” some critic named to simplify the experimentation, the development of a private language that signifies individual difference and is mostly inscrutable, not some trite similarity that is accessible to the public and easy to sell. The first guy was expressing existential longing in an original way; all you dopes who came after him made an eight by eighteen-foot Sherwin-Williams color sample for Arctic White. The first guy was a pioneer who wanted to express the idea that one could turn an industrially manufactured object into art with body English alone. His imitators are just leaving their things around.

The very notion that in the arts one way of seeing supplants another testifies to the particular person, the particular moment in time that made from nothing an antithesis to the status quo. The idea that the passage of one aesthetic order into another is in any way progress is absurd. We’re heading laterally, not forward. The compulsion to make stuff, impractical stuff like dramatic chalk lines on a cave wall, is always the same, an opposition to the most spectacular irony of man’s 100,000s of years on Earth: while every generation inherits the same problems, over millennia the language and technology we use to express the same old same old continually evolves until we lose track of the past and can’t communicate with it. Such knowledge as man may own has to be relearned generation after generation. Here we are, stranded in time, trying to discover the meaning of humanity all over again.

At its best, the revolutionary activity of articulating an individual life–free to a point, alone to be sure–confirms the existence of other souls in an inexplicable vastness. Don’t knock it; sometimes that’s enough comfort to carry on. Our job as artists is to offer our individual testimony in a human language, recognizable as the basic yearning to express oneself, to say we were here before time obliterated personhood, culture, and every remnant of our times. A weakling myself, I praise the courage of others to face the human condition absolutely alone, and I am so sad when some other soul’s representation of their joy and spirit can be signified by the towering vinyl Santa on their front lawn or the words to a sentimental ditty everyone already knows.

The Cook, the Thief, the Menu: A Brief

In 1990, I hosted a dear friend at my home on Dickinson Street in Philadelphia and suggested a videotaped movie for him to enjoy after my wife and I toddled off to bed. In those days, I was a copywriter for the national catalog of a major video retailer, and access to virtually anything on tape was a perquisite of my job. Thinking my guest would appreciate what I considered the best new release of the time, I slipped Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, & Her Lover (1989) into the Betamax, a well meaning choice that proved a complete miscalculation. My friend, a theatrical and world traveller, was horrified by the violent and repulsive opening sequence, and I had put him in the precarious position of frantically struggling in the dark to find the STOP button on an unfamiliar remote.

I was myself completely squeamish about moving images: I fainted watching the consequences of recklessness coming out of a 16mm projector in my driver’s ed. class; I nearly passed out at the exact same spot in The Exorcist both times I saw it in a theater. Despite my vasovagal syncope and depending on the cinematic genre, I was occasionally able to play an intellectual trick that overcame my fear of blood and gore, a capacity to become distracted from the dismembered hand by the hand of the artist. The switch in my head didn’t work so good on the average horror movie, when the filmmaker’s intention was to gross me out, but I found myself focusing on Greenaway’s artistry when he lushly depicted for satire’s sake the putrefaction of flesh and the vile corruptions of human nature.

“I don’t know much about you,” Greenaway told Catherine Shoard of The Guardian in 2010, “but I do know two things. You were conceived, two people did fuck, and I'm very sorry but you're going to die. Everything else about you is negotiable." This stark and practical principle provides the underlying rationale for the balance of the action in The Cook, the Thief.... Gangster Albert Spica either organizes or improvises unspeakable, violent outrages in the film starring Michael Gambon and Helen Mirren, yet his bloody, lurid handiwork merely adds a bit of panache to the eternal routines of Nature. Eighty percent of the movie takes place in Le Hollandais, a gourmet French restaurant Spica owns and where he dines every night, shouting his views on proper etiquette and good taste to the mooks in his crew and his much abused wife, Georgina, punctuating his tirades with foul language and physical assaults. The conceptual starting point for The Cook, the Thief… could be a pun about the difference between “taste” as in refinement and “taste” as in appetite. Greenaway’s beautifully filmed, trés elegant dining room and cavernous kitchen--all fire and copper pots--constantly remind us that eating, however refined, is fundamentally an organized slaughter. Spica demands our attention and spews most of the repulsive dialogue, but every creature kills to live.

The “negotiable” part of our severely circumscribed lives, which doesn’t alter so much as a pinch of salt nature’s basic formula of sex multiplying and death subtracting, is whether we conduct ourselves artfully, with style and grace, or brutally like the animals we truly are. Spica must have each extreme at once, manically pursuing a taste for refinement (a stylish wife in Jean-Paul Gaultier couture; a personal French chef) with the appetite of a wild boar. Reading from a menu, he mispronounces “poisson” so it sounds like something deadly; Georgina corrects him with the appropriate French word for “fish” and gets a series of brutal slaps for her trouble. Greediness in both its monetary and gastronomical connotations is the thief's defining characteristic. “My artistry,” Spica boasts, “is to combine making money with dining, business with pleasure.” Critics (and Greenaway himself) have called the movie a fierce satire of Britain’s Thatcher period, elevating raw consumption to a moral imperative and asserting (as Oliver Stone has it in 1987’s Wall Street) that “greed is good.”

An alternative justification for the movie’s violent depictions begins by noting that Greenaway belongs in the elite company of genuine film auteurs whose personal vision and technical prowess distinguishes their work in defiance of the collaborative sprawl of the typical studio production. A filmgoer might respond to the film’s cook as the singular composer of a work of art and the thief as representing the financial considerations demanding artistic compromises that steal from or outright destroy individual creativity. Like a chef and undisputed kitchen general, Greenaway marshals his production design team (Gaultier, Ben Van Os, Jan Roelfs, and Italian chef Giorgio Locatelli), the lavish cinematography of his long-time collaborator Sacha Vierna, Michael Nyman’s grand and operatic score (the composer also contributed to Greenaway’s A Zed and Two Naughts (1985) and Drowning by Numbers (1988)) to advance the formal construction of his own script, modeled after Oliver Goldsmith’s 1773 play, She Stoops to Conquer. (That five-act play contained a passionate dedication to Samuel Johnson. Have you read his book? 40,000 entries and not a single complete thought among them.) The result is a remarkable and remarkably disturbing film that serves up a full out rebellion of the arts against vulgar commercial interests. With such a losing formula, the dining room spectacle culture blogger Rhiannon Sian Wain called “the greatest British art house film” predictably earned less than eight million dollars in its initial U.S. release.

An alternative justification for the movie’s violent depictions begins by noting that Greenaway belongs in the elite company of genuine film auteurs whose personal vision and technical prowess distinguishes their work in defiance of the collaborative sprawl of the typical studio production. A filmgoer might respond to the film’s cook as the singular composer of a work of art and the thief as representing the financial considerations demanding artistic compromises that steal from or outright destroy individual creativity. Like a chef and undisputed kitchen general, Greenaway marshals his production design team (Gaultier, Ben Van Os, Jan Roelfs, and Italian chef Giorgio Locatelli), the lavish cinematography of his long-time collaborator Sacha Vierna, Michael Nyman’s grand and operatic score (the composer also contributed to Greenaway’s A Zed and Two Naughts (1985) and Drowning by Numbers (1988)) to advance the formal construction of his own script, modeled after Oliver Goldsmith’s 1773 play, She Stoops to Conquer. (That five-act play contained a passionate dedication to Samuel Johnson. Have you read his book? 40,000 entries and not a single complete thought among them.) The result is a remarkable and remarkably disturbing film that serves up a full out rebellion of the arts against vulgar commercial interests. With such a losing formula, the dining room spectacle culture blogger Rhiannon Sian Wain called “the greatest British art house film” predictably earned less than eight million dollars in its initial U.S. release.

Hanging prominently in Le Hollandais, an upscale dining destination that is nevertheless infested with the rats and cockroaches who are Spica’s crooks and hangers on (alt-film regular Tim Roth and New Wave rocker Ian Dury among them), is a vivid reproduction of the vast canvas Banquet of the Officers of the St George Militia Company in 1616, a revolutionary painting in its own right by the Flemish master Frans Hals. The artist integrates recognizable portraits of the most powerful men of Haarlem within an animated scheme instead of showing them stiffly as a static collection of disconnected likenesses. This advance on the conventions of the 17th century group portrait stands apart from the mannered Baroque style popular elsewhere in Europe and earned its author a secure living. Other references to 17th century oil painting include a lavishly presented view of the back of a food-laden van, recalling Flemish still lifes of foodstuffs by Lauren Craens and others, often allegorical pieces representing the life--and death--preoccupations of earthly man. By the middle of the movie’s week-long time span, the gate of the truck is thrown open again to reveal a stinking bounty of rotten carrion.

The Cook, the Thief… in its notorious opening sequence does a cute little number using letters like Scrabble tiles to suggest the corrupting relationship between crude Spica and highly refined Boarst. After making the kitchen’s food procuror literally eat shit because he didn’t get the restaurant’s fresh meats through Spica’s racket connections, the gangster proudly shows his chef partner the new, monstrous neon sign he’s had made that reads, “Spica & Boarst.” When he throws an electric switch to turn the sign on, the thing crackles and smokes from short circuiting. All the lights in the kitchen go out, and only a few of the sign’s letters remain both illuminated and unoccluded by a human figure. (“The kitchen is dark!” a line cook tells the chef. “Thanks to Mr. Spica’s generosity, it’s dark everywhere,” Boarts replies in his elegant French accent.) What remains visible now says “P & A BO ARS,” which is letter play suggesting the initials for the scatological references with which Spica is adolescently obsessed and either a corruption of the words “beaux arts,” the academic architectural style of Paris, or “b.o. arse.” “The naughty bits and the dirty bits are so near together,” Spica muses elsewhere, “it shows the close relations between eating and sex.”

Greenaway dramatizes Spica's threat to the arts through Georgina’s affair with Michael (Alan Howard), her bookish lover. They meet under Spica’s nose, trysting in the washroom and the kitchen storage closets, and clearly they risk death to do so. The chef, wearing the white uniform of an accomplished artisté, is a co-conspirator, taking their side. Boarst needs the monster’s cash to operate a restaurant, but he revolts against Spica in secret and at the first opportunity. In a motion picture where a gangster’s vile insults and bullying comprise the majority of the dialogue, the first nights of the wife and her lover are wordless, tender, physical explorations of love. They undress together in a stall in the loo; they taste each other in a closet area where a dozen freshly slaughtered pheasants are hanging, Georgina computing the number of times their lovemaking will be interrupted if the dining room has a run on wild game birds under glass.

Spica invites the man reading a book by himself in the restaurant to join the sullen and stupid thuggee entourage at their long table. His courtesy is a form of offense, since he has noticed his wife’s interest in the poor schnook and wants to expose Michael’s powerlessness and disqualification as a romantic rival. It is only during this tense encounter that the lovers learn each other’s names. Afterwards, Michael tells Georgina that he once lost interest in a film after the first wordless scenes, when the dialogue began. The cliché of the beautiful woman who was charming until she opened her mouth underlies the anecdote, but Greenaway is also revealing his particular affinity for Samuel Beckett, who despised language’s propensity to conceal and its clumsy syntax and grammar that obscure communication more than they foster intimacy. Meaning is impossible, and all that remains is elaborate word play and convoluted self-references. Spica, we learn, uses his bullying and bluster to conceal the fact that he can’t have a fruitful erotic relationship. Georgina confesses to her lover that relations with her husband involve his painful futzing ‘round with kitchen implements, exercises that have made it impossible for her to conceive his children. He poses the threat of violence to command and control, but he is not capable of procreation, only death.

Greenaway’s personal history and 2007 film Nightwatching informs our understanding of the Hals painting’s function in The Cook, the Thief.... Significantly, Rembrandt, one of the greatest artists in history, was himself crushed by the patronage system of the guilds. In Nightwatching, about a civilian militia who want to have their group portrait done in the official style of Hals, Amsterdam resident Greenaway suggests that Rembrandt’s allegorical representation of a revolutionary conspiracy in his supreme achievement The Night Watch primarily alienated him from the establishment guilds and thus doomed his personal fortunes. The cook Richard Boarst (actor Richard Bohringer) has a patronage arrangement with the gangster Spica, who wears a red sash like the powerful men in Banquet of the Officers, that anticipates his doom since pure art must inevitably be crushed by money and social power. Meanwhile, the girls in the cheesy cabaret act a pimp acquaintance of Spica has requested sing, "We're only here for love!"

Greenaway’s films are full of conspiracies and submerged plots. The paranoid seeing story skeletons everywhere is probably a disillusioned atheist who misses the comfort and joy of relying on a manifest Prime Mover, some great immortal to give meaning to all this confusion and chaos. In The Falls (1980), A Walk Through H (short film), and The Tulse Luper Suitcases (2003, 2004), the director utters the secret name of a dark personage who steals artists’ creations and flays their souls. Greenaway’s incessant glossing of his own catalog from one film to the next and his appropriation of touchstones in classical art history parallel the work of that other postmodern auteur, Quentin Tarantino, who also revives his early characters and properties (Red Apple Cigarettes, Fox Force Five) in later films, while referencing the icons of mainstream culture (Madonna! Bruce Lee!) in his screenplays. These auteurs project an elaborate labyrinth of self-citations over their individual ficciones, anchoring the made-up present in the historic past, like Alfred Hitchcock’s cameos to kick off North by Northwest or The Birds. It must be an accident that Michael Gambon's character resembles that most independent of directors, Stanley Kubrick, mustn't it?

In Beckett’s work lies the contradiction between the urge to express oneself evocatively, and the cold certainty that no amount of artistic eloquence can overcome the practical realities of hunger, kitchen, and hearth, or offer succor against the inevitability of death and decay. The thief's revenge against his wife’s potent lover--suffocating him by forcing the pages of a text on the French Revolution into the victim’s mouth with a spindle--Spica hails as a masterpiece of murder, but only irony makes it so, and irony is merely an artifact of language. Contrarily, Georgina ritualistically force-feeding her husband at gunpoint the flesh of his murdered victim manifests the ultimate taboo and is the corporeal revocation of Spica’s humanity. The occasion is marked on the title card/menu as a “private function” (more scatological punning, there), and the entire, much abused kitchen staff turns out to witness it.

Don’t you hate people who abuse the wait-staff? Most of them are incognito artists, you know. Poor Pup, the kitchen boy, suffers the worst of Spica’s temper. He sings the melancholy minor key intervals of Michael Nyman’s brilliant score in a pure soprano (the dubbed voice of Paul Chapman), and Spica constantly mocks his innocence. “Come on, sing damn ya. I was a choir boy once. Women love choir boys.” In one of his rages, the gangster tries to force Georgina’s sexuality onto the child, to corrupt him and silence the beautiful voice. Eventually Spica mutilates Pup, who has to be brought to the movie’s final supper in a wheelchair.

The minimalist music of the Michael Nyman Band, like compositions by Philip Glass and Stephen Reich, eschews the false narratives of melody, alternately employing musical chord progressions and variants of a simple theme. One can argue these variations mirror the repetitions in Greenaway’s plots. Three generations of Cissie Colpittses murder their husbands in Drowning by Numbers, in which the director goes so far as to contrive the passing scenery to include individual counting numbers, 1 to 100, to help the audience find their place. Through the basic drama of the lovers and the cuckold, all of the action of The Cook, the Thief…, consists of repetitions of the same outbursts on etiquette by the always angry dinner host in his same, nightly spot at table, while the lovers arrange themselves in various softcore sexual positions in different outposts in the vast restaurant. Greenaway’s plot constructions are like the Rocky movies: numbered for your convenience. Menu title cards listing the specialty du jour preview each variant of what is essentially the same scene over and over, until the film’s cannibalistic climax. Cannibalism in the arts is when the artist recycles his old material because the promise of creating something new is physically and psychically impossible.

“Cinema is dead. I’ll give you a date — August 31, 1983, when the remote control was introduced into the living rooms of the world. Cinema is a passive phenomenon. All the really interesting visual artists are now webmasters.” That was Greenaway’s pronouncement to Peter Noakes in 2007. Not nostalgic about the demise of the motion picture medium at all, he sees the “illustrated books” of linear motion pictures giving way to the environment of the web, where the viewer controls the sequence and duration of encounters with a variety of media and even a variety of commentators. Lists, like the alphabetized words in Johnson’s dictionary, predict the Internet environment in which we all live. These experimental works have occupied the director in recent years, like in his multimedia presentation of glosses on Da Vinci’s The Last Supper or his Peopling the Palaces at Venaria Reale, installed on-site, that animated the palace with 100 video projectors. With new technology, the artist must reinvent his presentations and hopefully advance forms of expression that require the active participation of the viewer/explorer. So to my visiting friend whom I left with the Betamax in 1990, fumbling for the remote, let’s not think of you frantically turning off a cinematic masterpiece. Instead, let us consider you were part of the start of something big.

January, 2021

Recently, I eked out a commentary that annoyed one potential reader, who wished I would write about more accessible films, or at least a movie he had seen. That’s cool, but to give an explanation for my process in choosing which art shows and movies to discuss--an explanation for which no one is asking--I have to think I have a different insight into my subject than most of its viewers, or why take the trouble to write something, and why ask people to read it? The exchange made me take a quick inventory in my head, nevertheless, to identify a movie nearly everyone has seen and few seem to fully appreciate: so, here’s my thinking about Stanley Kubrick’s most challenging film, A Clockwork Orange (1971).

I don’t just mean that it’s hard to watch. That would be Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999), which had perhaps the most unfortunate title of any release since The Nude Bomb (1980) starring Don Adams as Maxwell Smart. “Sorry about that, chief.” A Clockwork Orange, I think, is practically inexplicable without some contextual information, which isn’t to say it isn’t a visual masterpiece, and completely readable as a straight-up, dystopian strack, a right dobby cinny full of groodies, yarbles, and the old ultraviolence. Despite its visual appeal and truly inspired vision of a mad future dominated by Nadsat thrillseekers run amok, Kubrick’s masterpiece deserves some intellectualizing in the old mozg.

In roughly 1973, I read the Anthony Burgess novel upon which Kubrick faithfully based the movie, and I’ve read the lengthy commentary by the author that was republished in The New Yorker in 2012. A standout statement by Anthony Burgess in the latter is his insistence that novelists are essentially entertainers, and readers shouldn’t take the words of the author as evidence of an argument in support of a particular viewpoint:

In roughly 1973, I read the Anthony Burgess novel upon which Kubrick faithfully based the movie, and I’ve read the lengthy commentary by the author that was republished in The New Yorker in 2012. A standout statement by Anthony Burgess in the latter is his insistence that novelists are essentially entertainers, and readers shouldn’t take the words of the author as evidence of an argument in support of a particular viewpoint:

No creator of plots or personages, however great, is to be thought of as a serious thinker—not even Shakespeare. Indeed, it is hard to know what the imaginative writer really does think, since he is hidden behind his scenes and his characters. And when the characters start to think, and express their thoughts, these are not necessarily the writer’s own.

The caution to readers not to attempt to infer what the author means from how characters behave seems a bit disingenuous to me, but I’ll not flatly refute it. I will say that Burgess, in writing the tale of a violent youth who at first gets away with murder but eventually pays for his sins, intends to conform to the conventions of what reading professionals call story grammar. Man is a storytelling creature by nature who spins tales to present a fantasy world where certain behaviors result in satisfactory punishments and certain other behaviors result in just rewards. The real world doesn’t smite the wicked man and elevate the righteous (at least not in their own lifetime) but it is a perverse story indeed that doesn’t adhere to this edifying requirement that’s at least as old as Aristotle. Perhaps Burgess didn’t have a verbal formula in mind that A Clockwork Orange embodies, but so far as he calls himself an entertainer, we know he won’t present a tale that in its entirety offends the sensibilities of the public.

In modern stories, the justice to which every tale must conform may apply obliquely, letting certain crimes go unpunished while still elevating particular righteous ideals. The political hacks who use Alexander DeLarge as a test case for behavioral control are chastened in A Clockwork Orange through twists in the movie structure. After all, when Alex behaves abominably he rules like Alexander the Great, and when he is constrained by external controls to nothing but the straight and narrow, fate punishes him cruelly. Aristotles’ principles shape the satire in general, not the ledger of Alex’s behaviors in particular.

Another example where story grammar applies to the story and not the delayed comeuppance of an individual character is director John Dahl’s neo-noir thriller The Last Seduction (1994) from Steve Barancik’s screenplay. Bridget keeps the drug money, offs her sexual partners and anyone who gets in her way, and drives off in a limousine. The usual morality doesn’t apply to her movie behaviors; however, I would argue, in the noir category, story grammar applies to a satisfying expansion of typical story conventions that conforms to the notions of justice of movie-wise audiences who are hip to the play. The exceptionally performed, Linda Fiorentino character deconstructs the outdated--yet persistent--film convention of women as powerless victims who are used sexually by men and can’t realize their own destiny. The justice in film noir is the explosion of societal norms that have destructive and inhumane results. It’s the bad story arc that takes a spanking and the progressive screenplay that gets an approving chuck under the chin.

A Clockwork Orange defies conventional story tropes by seeming to glorify Alex’s destructive swath through Burgess’ surreal, but completely recognizable, urban landscape and by employing a doubled-on-itself plot, where Alex walks exactly the same path before and after his behavioral rehabilitation with completely opposite results. The plot and Kubrick’s brilliant visual depictions of violence so subvert ordinary expectations that filmgoers and especially the British public believed it glorified the depravity of Alex and his droogs. Particular instances of youth violence in London and elsewhere were dubbed copycat crimes, life imitating art (as if life EVER imitates art). The public outcry against Kubrick’s cinematic masterpiece was so intense, the director, forced into the impossible position of explaining a work of art, actually pulled A Clockwork Orange from British release, and it was not seen in theaters there for three decades, until after the director’s death.

Kubrick forcefully responded to the ironic suggestion that a movie about behavior modification and the origins of aberrant, antisocial actions, could itself inspire violence.

I know there are well-intentioned people who sincerely believe that films and TV contribute to violence, but almost all of the official studies of this question have concluded that there is no evidence to support this view. At the same time, I think the media tend to exploit the issue because it allows them to display and discuss the so-called harmful things from a lofty position of moral superiority.

Pop culture historians have argued that the tone and style of Clockwork Orange makes Kubrick the godfather of Punk, the violent musical genre that shocked the sensibilities of straight society and exalted anarchy and ugliness for its own sake, without artistic--or even melodic--justification. (I myself was so taken by Alex’s apparel that I made a paper mâché version of his work clothes for my Halloween costume in 1982, complete with bowler, codpiece, and nine-inch dicknose.) Understandably, Kubrick bristled at being made a forebearer in the lineage of the Sex Pistols.

Instead of intending to luridly stimulate aggression and degeneracy, Burgess’ narrative wants to raise questions about the existence of free will and whether the individual has a fixed nature and destiny. In the The New Yorker article where he plays the apologist for a novelist who manipulates story to present big ideas, Burgess expresses that he did set out to write a response to behaviorist B.F. Skinner’s ideas, compiled and published in Beyond Freedom and Dignity (1971), in which the revolutionary scientist emphasizes the need for the species to re-evaluate the impact of soul, consciousness, and all that gobbledegook on the actions men take, good or evil. Burgess recalls that (although the tenets of behaviorism had circulated for decades) B. F. Skinner’s book came out at the very time that A Clockwork Orange first appeared on the screen,

a book ready to demonstrate the advantages of what we may call beneficent brainwashing. Our world is in a bad way, says Skinner, what with the problems of war, pollution of the environment, civil violence, the population explosion. Human behavior must change—that much, he says, is self-evident, and few would disagree—and in order to do this we need a technology of human behavior. We can leave out of account the inner man, the man we meet when we debate with ourselves, the hidden being concerned with God and the soul and ultimate reality.

Skinner’s radical behaviorism proposes that people do not formulate actions in the consciousness and then perform them with their bones and sinews; rather, the physical body behaves according to the rewards or punishments it has received in response to past actions, and consciousness describes instead of motivates those behaviors. Reason provides the illusion of formative resolve, but one doesn’t need to say in their gulliver, “Clobber the ptitsa in the litso with the bolshy, penis-shaped statue,” to make it happen. Nor, Skinner would argue, do we behave in harmony with the laws of man and God due to the conditions of our souls, or if you’re a Calvinist, a predetermined destiny of damnation or salvation. Since the origin of behavior is the environment of consequences outside the organism, the state of mind, intention, and the health of the soul are irrelevant. Alter the menu of external consequences and alter behavior. Burgess, a devout Catholic, believed the will of man to do good or evil is essential to heavenly salvation or exile to the fiery furnace; furthermore, he considered Orwellian, a threat to personal freedom, Skinner’s idea that society should actively organize the system of consequences affecting the individual and condition their behavioral change.

After Alex bonks the yoga lady with a polyurethane penis sculpture that has a really awesome throb-rocking motion when stimulated, the police close in and capture him. Off he goes to prison, but rehabilitation proves impossibly difficult. To change the gangster’s violent patterns, the prison chaplain appeals to Alex’s understanding of the state of his soul, and as we know from Skinner’s analysis, you can’t change a lad’s behavior by mucking around with his conscience. Reading the Bible fervently, Alex becomes consoled in his penitentiary isolation by the sex, the violence, and the cruelty of man to his fellow man it glorifies. Even if one places the locus of control for behavior outside an organism rather than inside, problematic is identifying which outcomes the subject will deem beneficial to himself and which he will call detrimental. People’s behaviors often seem completely unconnected to the prevalent stimulus, and “PERVERSION,” as Poe writes, “is a dominant characteristic of man’s nature.” I also enjoy employing Plato’s axiom, that no man will do bad if he knows what is the good. It isn’t so useful as Poe's, but I like to repeat it.

After Alex bonks the yoga lady with a polyurethane penis sculpture that has a really awesome throb-rocking motion when stimulated, the police close in and capture him. Off he goes to prison, but rehabilitation proves impossibly difficult. To change the gangster’s violent patterns, the prison chaplain appeals to Alex’s understanding of the state of his soul, and as we know from Skinner’s analysis, you can’t change a lad’s behavior by mucking around with his conscience. Reading the Bible fervently, Alex becomes consoled in his penitentiary isolation by the sex, the violence, and the cruelty of man to his fellow man it glorifies. Even if one places the locus of control for behavior outside an organism rather than inside, problematic is identifying which outcomes the subject will deem beneficial to himself and which he will call detrimental. People’s behaviors often seem completely unconnected to the prevalent stimulus, and “PERVERSION,” as Poe writes, “is a dominant characteristic of man’s nature.” I also enjoy employing Plato’s axiom, that no man will do bad if he knows what is the good. It isn’t so useful as Poe's, but I like to repeat it.

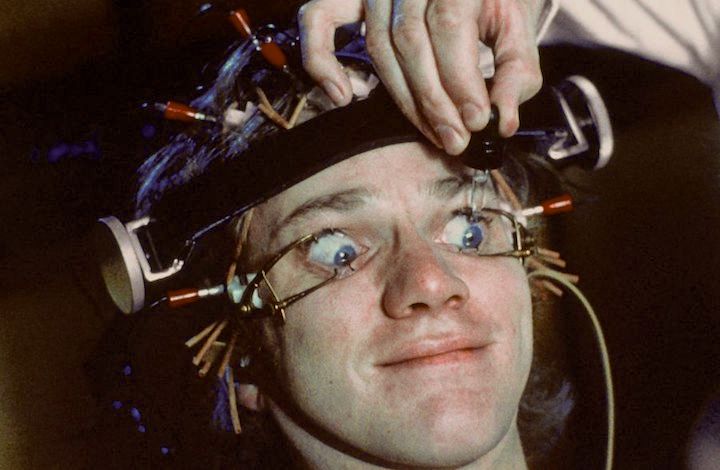

Kubrick’s film’s technological solution to the input/output problem of altering behavior controls precisely what data Alex receives from his senses and exactly his visceral response to it. Laboratory technicians program the subject to become violently ill, to want to “snuff it” in fact, when what were once enormously pleasurable stimuli, like sex and violence, appear in his external environment. The “eyes wide open” apparatus attached to actor Malcolm McDowell’s skull, forcing him to focus on prepared moving pictures of rape and murder, is perhaps the best known image in A Clockwork Orange, and it perfectly represents the state-controlled reprogramming of human behavior that Skinner predicates and Burgess abhorred. Of course, that a purely evil image of the application of exterior force to alter the will of man and coerce him to conform to societal norms instantly identifies Kubrick’s most challenging motion picture perversely contradicts its notoriety as the origin of Punk and inciter of random delinquency. “C’est la vie,” say the old folks, “it only proves you never can tell.”

B. F. Skinner notoriously raised his own infant children in devices that controlled their sensory input, controlled room temperature, controlled human contact. Reportedly, Skinner’s kids grew up to be fairly normal citizens. (So, was it worth it?) The great scientist recognized, I think, that his anti-Freud, counter-intuitive, model of human behavior contained terms--“environment” and “positive consequence” especially--that were difficult or impossible to define given the complexity of the human condition. He tried to refine the experiment, but it’s impossible to inventory the exterior reality of actual, walking-around people, and thus impossible to observe or control every stimulus motivating their behavior. Additionally, differences in human perception profoundly affect individual’s predictions of how their actions will affect outcomes. In fact, the impossibility of measuring what goes on in the old mozg, dere, is a fundamental stipulation of Skinner’s entire science.

Reality itself is a relative term, as exemplified in Burgess’ novel by the invention of a whole different language, Nadsat, to describe it. Anthony Burgess (1917-1993) was acclaimed for his brilliance in the field of linguistics, and one of his other influences on film was creating the languages used by the primitive humans in Quest for Fire (1981). With huge implications for our evolutionary adaptation, we communicate experience to one another, including our predictions of positive or negative outcomes for behaviors, using words that are so trendy as the lavender Edwardian get-up Alex wears to shop for the latest fuzzy warbles by Ludwig Van at his local record shoppe. Connotations in speech are especially volatile and especially fluid, as any reader of Shakespeare’s plays who’s using an unannotated version must soon discover.

In addition to the fluidity of slanging speech, which constantly gives the old 23 skidoo to temporary mores and public fads, the influence of new technology introduces brand-new language to convey it. Consider Kubrick’s use of Wendy Carlos’ brilliant Moog synthesizer performances of Elgar, Purcell, and Beethoven classics that are melodically consistent with the composers’ clavichord or orchestral originals, and yet morph into a form completely consistent in their radical, hyper-modern connotation with the landscape of sex and violence inhabited by Alex and his gang.

Indeed, the trendiness of what we imprecisely call “reality” is essential to a deep understanding of A Clockwork Orange. Its formal doubling over of Malcolm McDowell’s progress through the world has to do with the impact of new technology on penal science and the fleeting influence of liberal politics giving way to more conservative points of view or vice versa. (McDowell’s performances in this film and Lindsay Anderson’s less known O Lucky Man! (1973) establish him as the last century’s cinematic Everyman, the ideal pilgrim.) We are left to imagine the make-work political policies that turn Alex’s droogs from thuggish criminals to thuggish officers of the peace, and of course we must consider how these same temporary societal pressures change Alex from scourge, to victim, to cause celebre in under 141 minutes. What Anthony Burgess is too timid to admit, that plots of a novel admit an intention, is revealed by the story grammar of the text through a most Skinnerian method: invisible intention is irrelevant to our judgment of A Clockwork Orange; the story’s meaning is completely conveyed by its behaviors.