Our walking tour of prominent public sculpture around City Hall in Philadelphia begins with an exemplar of civic pride and industry. City Hall is the world's largest masonry building and has been called the epitome of the Second Empire architectural order. Intended to be the world's tallest structure when it was designed, by the time City Hall was completed after 30 years, it had been surpassed by the Eiffel Tower and the Washington Monument obelisk.

Called a massive boondoggle during the three decades of its construction, the largest city hall in America celebrated the history of Pennsylvania and Philadelphia, and boasted of the wealth of its merchant class. In 1870, Philadelphia was the largest municipality in the US, still the place where Benjamin Franklin in the early 1700s had journeyed from Boston seeking opportunity, and Centre Square, the site of the new municipal building, was on a public set-aside provided by William Penn himself in 1682. Rectitudinous capitalists like John Wanamaker believed in a government of the people that gave sensible businessman a free hand. The breathtaking spectacle of City Hall, decorated with fully articulated statues depicting Pennsylvania culture, is a celebration of the city that nurtured the success and fortune of its wealthiest citizens.

The marble, limestone, and granite building was designed by John McArthur Jr. and Thomas Ustick Walter, although the 250 separate sculptures adorning the structure were produced by Alexander Milne Calder. His masterpiece is the 37-foot-tall, bronze statue of Willam Penn atop the City Hall tower, the tallest such adornment in the world. William Penn weighs over 53,000 pounds, requiring crews of workers to hoist it to its pedestal in 14 sections. Calder wished the face of Penn to look south and stay in sunlight most of the time, but he is turned in perpetual shadow, facing Penn Treaty Park on the Delaware River, reputedly because the building contractor disliked the bronze behemoth or its sculptor.

Our tour would begin inauspiciously with stiff necks and strained vision if we were asked to peer high up on City Hall's façade to appreciate the details in Calder's modeling.

Fortunately, we are able to see small sculptures close-at-hand in the ground-level, north-south passage crossing under City Hall. A particular chamber along this passage has four different designs attached to keystones supporting the arches. They include a fierce lion, a heraldic owl, and an ordinary moo cow. Elsewhere on the façade, Calder depicts animals and plants native to Philadelphia, but the inclusion of the lion here suggests traditional iconography: these animals could be metaphors for strength, wisdom, and fertility, instead of a literal catalog of local fauna. In any case, our up-close look at City Hall's architectural details satisfies us as to their workmanship and vividness. The modern skyscraper eschews such ornamentation as dramatically covers every part of this building, and perhaps that and its lack of steel girders explains why to some visitors City Hall seems more antiquated than relevant a hundred and twenty years after its dedication. Hopefully the values of pride in place and civic duty it espouses still thrive in the present.

Fortunately, we are able to see small sculptures close-at-hand in the ground-level, north-south passage crossing under City Hall. A particular chamber along this passage has four different designs attached to keystones supporting the arches. They include a fierce lion, a heraldic owl, and an ordinary moo cow. Elsewhere on the façade, Calder depicts animals and plants native to Philadelphia, but the inclusion of the lion here suggests traditional iconography: these animals could be metaphors for strength, wisdom, and fertility, instead of a literal catalog of local fauna. In any case, our up-close look at City Hall's architectural details satisfies us as to their workmanship and vividness. The modern skyscraper eschews such ornamentation as dramatically covers every part of this building, and perhaps that and its lack of steel girders explains why to some visitors City Hall seems more antiquated than relevant a hundred and twenty years after its dedication. Hopefully the values of pride in place and civic duty it espouses still thrive in the present.

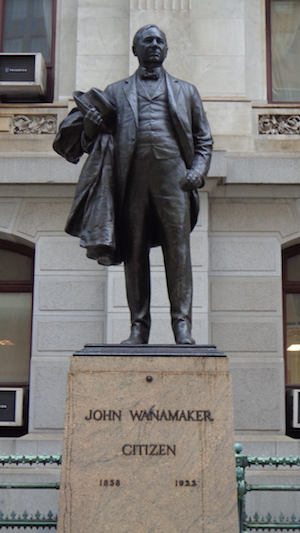

Going east along a courtyard passage to Market Street, on our left we find a monumental, eight-and-a-half foot statue of John Wanamaker, "Citizen," as its pedestal reads. Because statues of great men usually portray them in the ornate and complex costumes of long-past centuries, the sight of a bronze giant in an ordinary business suit can be disconcerting. The sculptor John Massey Rhind had only the features of Wanamaker's sagacious head poking out of a standard collar with which to establish a likeness; that, and he depicts this citizen as particularly well fed.

A representation of the most prominent member of the Philadelphia merchant class extends the City Hall theme of civic responsibility, especially by those who have most benefited from Philadelphia's cultural infrastructure,

its government, schools and universities, hospitals, philanthropic institutions, and industrious working class. Wanamaker lived in a city with a rising consumer class that he induced to shop at his modern "department store" with innovations such as a money-back guarantee and fixed pricing. He was a pioneer in the use of advertising who enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship with the local newspapers: they had the readership and he had the advertising dollars. Wanamaker paid for the first ever half-page advertisement, and later became the first to buy a full pager.

its government, schools and universities, hospitals, philanthropic institutions, and industrious working class. Wanamaker lived in a city with a rising consumer class that he induced to shop at his modern "department store" with innovations such as a money-back guarantee and fixed pricing. He was a pioneer in the use of advertising who enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship with the local newspapers: they had the readership and he had the advertising dollars. Wanamaker paid for the first ever half-page advertisement, and later became the first to buy a full pager.

John Wanamaker's civic-mindedness may have contributed to his desire to become a US postmaster general (the papers said he bought the appointment from President Benjamin Harrison), where he innovated the first commemorative stamp. He contributed to many cultural and philanthropic causes, including founding the Sunday Breakfast Rescue Mission and financing a campaign to make Mother's Day a recognized holiday. Famous for promoting thrift, Wanamaker inspired school children all over his city to collect $50,000 in pennies towards the creation of his statue after his death.

Scottish sculptor John Massey Rhind was a leading creator of portrait statuary at the beginning of the twentieth century, whose dozens of historical subjects are found across the country, including in the National Statuary Hall Collection in the Capitol. In Philadelphia, he created the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Memorial on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway and the Lenape Warrior placed by the Wissahickon Creek. Rhind supervised Alexander Milne Calder's apprenticeship in sculpting back in Scotland.

Turning the corner from the statue of Citizen Wanamaker, the walking tour crosses JFK Boulevard to attain One Broad Street,

Visitors to the Grand Lodge pass through a series of nested arches marked with abstract designs. In contrast, we have seen how the generically named City Hall decorates an archway with quite literal lions and bulls. Restraining the figurative representation of any part of God's creation invokes Eastern religion, which is just so well misunderstood here in Philadelphia that it may as well be some really cool hocus pocus to scare the bejeezus out of guys. Additionally, the series of arches relates to the initiation of the Freemasons and their elaborate hierarchy of "accepted" members. While City Hall embodies the principle that all men are free and equal partners in civic government, the Masonic Temple represents a strict social hierarchy where the merits of individuals are carefully weighed and those who are lacking may not enter. We are told that the Grand Poobah of the Philadelphia Lodge made John Wanamaker a high ranking Brother "on sight." The statue of the man is right across the street, evidence of what could be perceived about him from mere appearance: mainly, he was white, male, and wealthy.

The tour is not alone. We share the sidewalk with a pair of very conspicuous Freemasons, represented in bronze and meeting "on the square," as it were.

This near to City Hall, we've seen several sculptures in a realistic style, used to describe a historical subject and in that way commemorate it for the edification of the public.

As one of several institutions that has an influence on public sculpture in Philadelphia, PAFA endorses work whose subject is the multitude of ways we understand existence, veering away by a couple of blocks from the civic-minded purposes of the great men posed on and around City Hall. In a city with a profound respect for the cultural and financial benefits of its stellar educational and artistic academies, PAFA gives expression to Oldenburg's satirical gesture without sacrificing the hoary respectability of the school that trained Thomas Eakins and made him the head of their painting department. Paint Torch ironically presents a monumental artist's brush loaded with glossy, orange pigment, and that's a fairly good emblem for the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts next door. By scaling up an ordinary tool to enormous size, the artist demands our tour realizes that, while the formal content of the paint brush remains, its utilitarian object is no more. What is left is an angled erection flicking an iridescent glob, a stark, nudge nudge metaphor for the act of creation.

Staying on this side of Broad Street, let's walk back towards City Hall,

Commissioned by the city of Philadelphia, the great Cubist sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, then living in New York, had produced a plaster model for the 200th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Two of his sculptures were already in public spaces in the city, Prometheus Strangling the Vulture on the steps of the Philadelphia Art Museum, and Spirit of Enterprise along Kelly Drive in the Samuel Memorial Sculpture Garden. Not immediately accessible cognitively to those who are unfamiliar with the Cubist style are the works' abstraction of human and animal forms and their reckoning with the puzzle that is human visual perception, the problem of representing in a static medium living objects that exist in 360 degrees and from moment to moment.

Flexing a muscular apparatus operating outside City Hall, namely philanthropic investors in culture and other art people, the Fairmont Park Commission raised $350,000 to complete the casting of the 33-foot sculpture in bronze. By means of this clever stratagem, objections that the average citizen wouldn't understand the work were neutralized. "If they didn't pay for it, they don't have to look at it." Of course, in the ensuing decades, Lipchitz's pyramidal form showing generations of men and women supporting each other to achieve a vibrant government has come to be an accepted and even cherished part of the downtown scene. In a radio broadcast, even Mayor Rizzo admitted that his chauffeur was a fan of Government of the People. "That's what's great about this town. It has something for everybody!" Art critics called Lipchitz's last major sculpture a magnificent capstone to a career that was unceasingly idealistic and endorsed the struggle for freedom and self-realization.

Like other commemorative statues of great men, the realistic style of the Frank L. Rizzo Monument encourages appreciation of the breadth of the subject's life in addition to the straightforward reportage of his dimensions. At nine-foot,

Unfortunately for sculptor Zenos Frudakis' evocative Rizzo monument, affection for the legend of the late mayor has dimmed, and the legend comprises the largest part of what recommended the bronze behemoth to the public in the first place. No longer thrilling is the story of Hizzoner leaving a formal banquet in a tuxedo to wade into a brewing riot with his nightstick tucked into his cummerbund or breaking his hip when, policing a South Philadelphia refinery explosion, he was run over by a fire truck. The mayor's bluster and populist demagoguery are viewed as divisive of the community, not representative of it. In 2017, current Mayor Kenny stated that, like statues of Confederate generals in the South, it was time for Frank Rizzo to give ground. Maybe it would have been less a target of revision had the bronze portrait been made of paper mâché and tucked away in a less obvious corner on the inside of City Hall, as in the mid-'Aughts was my own

The Mayor of Heaven, a Mummery.

Let us move away for the time being from the controversial give and take between popular sentiment and educated art opinion, or private and civic interests. On the 15th Street side of the Municipal Services Building may be found George Greenamyer's lighthearted Philly Firsts. The wire, tin plate, and colorfully painted assemblage uncontroversially illustrates local history-making events such as the performance of the first circus, Frank Furness' design for the PAFA building, the first fire brigade, and Betsy Ross' stitching of the first national flag.

By some measures the most renowned sculpture on our walking tour, Robert Indiana's Love Statue may be viewed in Love Park (JFK Plaza) from 15th Street at the top of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway.

On his web site, the late sculptor describes the viability and pertinence of simple words and their lettering as a subject for art, a practice that originates in early 20th century collage works and paintings of Kurt Schwitters, Picasso, Leger, and others, through the Pop era, including Lichtenstein, Warhol, Rosenquist, and Jasper Johns. The artist elucidates the circular form of his composition, the clockwise flow of the letters, and the reference to the circular in the "o" made conspicuous by its tilting. Jasper Johns has said certain forms like flags, targets, maps, and trademarked logos are so ubiquitous we don't even perceive them as representations; they are forms excluded of content, pure abstraction. Whether Robert Indiana intends this work as a benediction for visitors to Philadelphia or a graphic design stripped bare of meaning makes a worthwhile question to ponder as we cross two streets and proceed to 16th and the Parkway.

Near an upscale cafe stands a reddish stone monolith so modest in its achievement one is tempted to think it's the cafe's mascot,

Our tour could have walked right past this sculpture on the way to some truly remarkable works less than half a block away, but in its semi-forlorn simplicity it has the needy appearance of one of Al Capp's lovable shmoos, the happy friend of man that offers itself up for easy eatings, or the old man who's a regular subsidiary character on The Simpsons. In earnest, let us acknowledge that the graphic simplicity of the Love statue offers that piece a presence and authority, which is a much different result than appearing only partially conceived. Our walking tour contrives to weave several themes marching from station to station, but it is worth being reminded of the fact that the placement of each has an element of randomness, defying meaning and an overarching design.

Heading towards 17th Street, we find Henry Moore's remarkable emerald form, weathered bronze on a black granite base, his Three Way Piece Number 1: Points, purchased and placed by the Fairmont Park Commission soon after it was cast in 1964. Moore stated that the best of his sculptures were made for the outdoors, and in so far as this one rests on a thin strip of lawn, we can appreciate it in a complimentary situation.

The title of Moore's work informs us it's abstract, and that, like Government of the People, it unfolds to the eye differently depending upon from which angle a viewer regards it. Three Way Piece doesn't possess a front and a back. Although it isn't representative of a specific subject, it does carry a signature quirk of Moore's sculptures: a large mass held up by a tiny leg, evocative of the singular anatomy of birds and the birdwatching pastime that is a favorite in the English countryside where Moore spent his childhood and had his studio. On our tour, we've said enough about the deficits of the neighboring Prophet, but let us appreciate Moore's mastery in comparison to the earlier sculptor at abstracting the particulars of actual living creatures. He suppresses singular details while revealing the underlying form. Moore stated that the best schooling he received as an artist was examining the history of art in the British Museum, where he was deeply affected by the sculpture of ancient civilizations that generalized the characteristics of the human body rather than realistically and exactingly representing them.

Just a few paces down the Parkway brings us to the intersecting steel plates of Three Discs, One Lacking, an abstract by Philadelphia's favorite son, Alexander Calder. His grandfather was responsible for the William Penn statue and other decorations on City Hall; his father, Alexander Stirling Calder, produced the splendidly lush Swann Memorial Fountain, in Logan Circle on the Parkway, and the powerful Shakespeare Memorial a few blocks away, in front of the main branch of the Philadelphia Free Library.

Constellations, mountains, geometry, and gravity itself inspire Calders abstractions, but his workmanlike skill with metal and playful exploration of what the materials are capable generate his familiar mobiles (a name given them by Marcel Duchamp) and stabiles (so dubbed by Jean Arp). Anyone who has ever struggled with steel wire has only to see the tight coils, precise crimping, and accuracy of Calder's wire portraits to appreciate his mastery with metal.

Calder studied in Paris as a young man, and he initially built a reputation for creative ingenuity with his suitcases full of circus puppets, from which he would regularly perform. Film of his circus recital curated by the Whitney Museum reveals the artist's undeniable personal charm and indelible sense of humor, and these qualities imbue his sculpture. Philadelphia is the home of Calder's largest mobile, in the Federal Reserve Bank on 6th street and accessible after an airport-style security check. From the Great Hall of the Philadelphia Art Museum, Alexander's mobile Ghost, his father's Four Rivers Fountain, and his grandfather's statue of Penn are simultaneously visible.

Letting Calder's discs, absent and otherwise, point the way to 17th Street, we encounter Barbara Hepworth's Rock Form (Porthcurno),

Donated by art patron David Pincus to the Association for Public Art in 2011 and installed the following year, Rock Form (Porthcurno) is cast in bronze, the ancient preference for monumental sculpture but not the material in which Hepworth developed her unique vision. Like Moore, she had an affinity and aptitude for carving, especially in wood. Carving and chiseling are much different processes than modeling in clay and making a plaster cast to be developed at a foundry as a bronze final product. Subtraction describes the work of a chisel, while addition is the nature of sculpting in clay. For artists who were keenly interested in the interior of objects, to integrate them into and evoke a landscape, the steady reduction of material is organic to the finished effect. Like a prehistoric native hollowing out a canoe, Hepworth first worked with huge trunks of trees to form her curvilinear interiors that surround the viewer's searching gaze. Conscious of her worldwide reputation and having a mind to create from a global perspective, Hepworth began to work in weatherproof bronze because its products more sturdily survived transportation across long distances and could be placed directly in the landscapes that inspired their creator.

As we approach the final leg of our walking tour of Center City public statuary, let's turn south on 17th Street to just below Market Street, where we will find Roy Lichtenstein's wry, monumental Brushstroke Group on the righthand side. Fabricated of half-inch aluminum coated with pigment used to paint airplanes, the work is in Philadelphia through the efforts of The Association for Public Art, the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, and Duane Morris LLP, one of the city's prominent law firms and the owner of the adjacent building.

Lichtenstein (1927-1997), along with Warhol, Oldenburg, Indiana, Rauschenberg et al, is a preeminence of art's Pop heyday in the 50s and 60s, but the appearance of these brushstroke monuments all over the planet, including the Mediterranean harbor of Barcelona, establish his relevance to the modern discourse about the nature of Art. Pop most importantly turned on its head the idea that High Culture was the appropriate source for the themes and images in serious art, and its proponents incorporated movie stars, advertisements, and mass-market printing processes into their canvases and assemblages. Lichtenstein's series of paintings faithfully appropriating panels from romance comics are establishment icons, today. Besides its use of industrial materials, pop culture imagery, and its diminishment of the importance of classical painterly technique, Lichtenstein's work is an antithesis to the Abstract Expressionism that first located American artists in the forefront of worldwide art consciousness

Abstract Expressionism, having its own ax to grind with its predecessors, insisted that painting should eschew material subjects (landscape or portraits, for instance), and that the proper subject of painting was painting itself. The hand of the artist and her visceral gestures on the canvas, even the materiality of paint, became the essence of their big pictures. What Lichtenstein's work satirizes is the idea of painting about painting. Here, he has idealized the brushstroke using industrial materials and manufacture, creating a monument to painting itself that is literally called Brushstrokes, but doesn't contain a single remnant of the handmade painting process. The ironic subject of these playful constructions revises once again our concept of what art should be; a comical relativism towards ideologies and a disdain for every establishment restriction on what the artist should do is Lichtenstein's treasured legacy.

That being said, our next stop brings us to a work so radical and elevated in the consciousness, that, well it doesn't even exist! At least, it isn't physically on our path. Milord la Chamarre, which translates as "the noble in the fancy vest," is a 24-foot high, stainless steel and black epoxy paint construction weighing 5000 pounds, including its granite base. Created by French artist Jean Dubuffet, the statue until recently rested in a niche on Market Street, between 15th and 16th streets, but as of this writing only a bronze plaque remains to mark its former presence. Take heart: the statue is close by,

in the adjacent atrium of the building, One Centre Square, a headquarters of the corporation that bought it. Inquirer art critic Roberta Fallon derided its original Philadelphia placement in this isolated niche as a supreme act of stupidity, considering the world-class reputation of Dubuffet, whose imaginary landscapes, made of such synthetic materials as polystyrene, polyester, and epoxy resin, sprout up like mushrooms in major urban centers like Manhattan and Chicago. An article in the

New York Times related the mostly scornful opinion of passersby when this same work was on display in front of the Seagrams Building, with one woman describing it as looking like "the Frankenstein monster in armor."

in the adjacent atrium of the building, One Centre Square, a headquarters of the corporation that bought it. Inquirer art critic Roberta Fallon derided its original Philadelphia placement in this isolated niche as a supreme act of stupidity, considering the world-class reputation of Dubuffet, whose imaginary landscapes, made of such synthetic materials as polystyrene, polyester, and epoxy resin, sprout up like mushrooms in major urban centers like Manhattan and Chicago. An article in the

New York Times related the mostly scornful opinion of passersby when this same work was on display in front of the Seagrams Building, with one woman describing it as looking like "the Frankenstein monster in armor."

Ironically, it wasn't the man on the street that Dubuffet was hoping to offend. Au contraire! His career-long target was the art establishment, especially art schools and institutions, whom he said corrupted the creation of art with their materialistic, commercial, and decidedly bourgeoisie values. He was a vocal champion of Art Brut, a name he coined for outsider art that escaped the trappings of establishment culture. Dubuffet favored the art of shut-ins and "primitives," artists whose sensibilities were so far off the beaten track, some of them were literally in asylums. Dubuffet's experience of the empirical world was outlandishly heterodoxical, thus his endorsement of even the most individual point-of-view. Of his (to typical persons) fanciful creations like Milord la Chamarre or the l'Hourloupe series of landscapes and figures, he insisted he actually saw them, that they weren't imaginary. Whatever this statement indicates pathologically about him, Dubuffet certainly recognized that seeing is an activity that takes place in the brain and consciousness, not in our optical hardware, an opinion that appears in similarly radical form in statements by the sculptor Alberto Giacometti and the mystical writing of Carlos Castaneda. Despite its extra-dimensionality, Dubuffet's statue reconciled over time with the perception of Philadelphia traffic on Market St: in these parts it became known as "the Mummer."

Soon after the installation of Clothespin, a chorus of ridicule that attended it was joined by one Philadelphia native who complained, a laundry staple was an inappropriate topic for public art. Well, here's the thing: on a monumental scale, a household object becomes something else, something necessarily greater than its humble origins. Belying its title, Oldenburg's stainless steel-clipped giant isn't a practical object; it merely resembles one. For Modern art, Magritte's warning about a curved smoking pipe, painted in oils, "Ceci n'est pas une pipe," has become absolutely crucial to understanding. Every art work is metaphorical, as in fact is every utterance in human language. We use symbols to describe experience: "real" events and imaginary ones, it's all the same, and symbols are the only means available with which to communicate with others. Oldenburg himself said his piece referred to the interlocking human figures in Brancusi's seminal sculpture The Kiss, enshrined at the art museum down on Eakins Oval. Stridently realistic or impudently fanciful, every work on our tour has more akin to ideas and abstract sensibilities than they do to actual persons or events. Today, even the public at-large appreciates the statue that has rightfully become a city landmark.

Hopefully, our walking tour has generated a lively inquiry

(All photographs by Drew Zimmerman, except Milord la Chamarre, by Alex Rogers for the Association of Public Art.)

"Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden." tate.org.uk, Tate Museum, 13 Sep. 2019, https://www.tate.org.uk/visit/tate-st-ives/barbara-hepworth-museum-and-sculpture-garden. Brenner, Roslyn F. Philadelphia’s Outdoor Art, 3rd edition. Philadelphia: Camino Books, Inc., 2002. "Brushstroke Group (1996)." associationforpublicart.org, Association for Public Art, 13 Sep. 2019, https://www.associationforpublicart.org/artwork/brushstroke-group/#. "Claes Oldenburg, Paint Torch (2011)." pafa.org. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 13 Sep. 2019, https://www.pafa.org/museum/history-pafa/buildings/ lenfest-plaza/claes-oldenburg-paint-torch. "Clothespin." associationforpublicart.org, Association for Public Art, 12 Sep. 2019, https://www.associationforpublicart.org/artwork/clothespin/#. "Frank L. Rizzo Monument." associationforpublicart.org, Association for Public Art, 12 Sep. 2019, https://www.associationforpublicart.org/artwork/frank-l-rizzo-monument/#. "Government of the People." associationforpublicart.org, Association for Public Art, 12 Sep. 2019, https://www.associationforpublicart.org/artwork/government-of-the-people/#. "Henry Moore's Sculptures." tate.org.uk, Tate Gallery, 13 Sep. 2019, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/henry-moore-om-ch-1659/henry-moores-sculptures. "John F. Collins Park." centercityphila.org, Center City District Parks, 13 Sep. 2019, https://centercityphila.org/parks/john-f-collins-park. "John Wanamaker." associationforpublicart.org, Association for Public Art, 12 Sep. 2019, https://www.associationforpublicart.org/artwork/john-wanamaker/#. "Love." associationforpublicart.org, Association for Public Art, 12 Sep. 2019, https://www.associationforpublicart.org/artwork/love/#. "Masonic Temple (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)." Wikipedia, Wikipedia, 13 Sep. 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masonic_Temple_(Philadelphia,_Pennsylvania). "Robert Indiana." robertindiana.com, Robert Indiana, 14 Sep. 2019, http://robertindiana.com/. "The Surprisingly Heart-Wrenching History of Robert Indiana’s ‘Love’ Sculptures." mymodernmet.com, My Modern Met, 14 Sep. 2020, https://mymodernmet.com/love-sculpture-robert-indiana/. "THEartblog's Roberta Fallon Shares Her Favorite Public Art." philly.curbed.com, Curbed Philadelphia, 13 Sep. 2019, https://philly.curbed.com/2012/6/27/10357928/artblogs- roberta-fallon-shares-her-favorite-public-art. "William Penn." associationforpublicart.org, Association for Public Art, 12 Sep. 2019, https://www.associationforpublicart.org/artwork/william-penn/#. "Your Move." associationforpublicart.org, Association for Public Art, 12 Sep. 2019, https://www.associationforpublicart.org/artwork/your-move/.

©Drew Zimmerman, 2024