Art Too Bruté

In my five decades of tracking down artwork in museums and galleries, the most moving exhibition I ever saw wasn’t one I was expecting to induce tears. On other trips, I journeyed to Chicago to see Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte; I made it to the MoMA before Guernica was returned to Spain; I saw pieces of the Parthenon on the Acropolis in Athens and in the British Museum in London. Seeing icons of the canon of Western Art in person deeply satisfies, and inevitably the visitor finds elements of scale or color or context no mere photograph conveys, but the time tears streamed down my face in the presence of art wasn’t one of those times I was mentally comparing the actual work to a colored plate in a monograph.

Outsider artist and novelist Henry Darger (1892-1973) amassed a 15,145-page work bound in fifteen volumes, with three of them consisting of several hundred illustrations of his subject, the Vivien Girls and their adventures in the Realm of the Unreal.

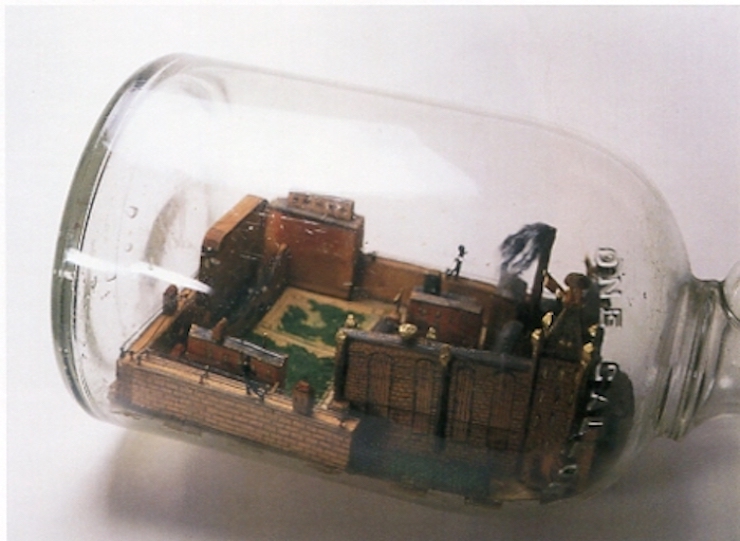

The most moving exhibition I ever saw was at New York’s American Folk Museum in 2003, The Perfect Game: America Looks at Baseball. The collection presented works by renowned, “outsider” artists like Thornton Dial and Elijah Pierce, but mostly they were created by unidentified baseball fans. Particularly affecting for me were anonymous representations of baseball stadiums crafted by prison inmates, like the whimsy bottle containing a tiny Maryland State Penitentiary, composed of painted and carved wood slivers, with a ballfield in its courtyard. Baseball as a theme appealed to me because I love that game and the Americana it represents; additionally, I recognized the compulsion of the artists to record their experience as fans, and an unobstructed view of the mental environment of the creator vividly recommended these painstakingly amassed, eensy-weensy cathedrals of sport.

A whole category of art comes into existence to materially connect the artist to an absent subject. Craft restores a treasured person, thing, or idea abandoned in the past or else physically unavailable in the artist’s present. The material nature of the created object matters much more than does the presence of a painting or sculpture in an art museum. Whether because it conveys specific ideas and aesthetics rather than a visceral presence or because it is so readily available in secondhand sources, Modern Art especially may be understood a priori. After all, Guernica is known much more than it is experienced. One must go to Spain to literally see it, and even should you make the trip, the El Reina gallery has long lines of hot and crabby tourists, and wouldn’t it be more fun and more memorable on a pricey vacation to Madrid to sample the cocido madrileño at a local cafe? Picasso’s masterpiece is available-- except for its scale-- in printed reproductions and voluminous commentaries; the private artist building a model of a ballfield in a bottle does so to create a specifically physical presence to compensate for the absence of that which only exists in memory--or nowhere at all.

Proposing his own radical art aesthetic, Jean Dubuffet infamously championed what he called “Art Brut,” which was work created free from the influence of formal academies or commercial galleries. Art produced by shut-ins, inmates, and the clinically insane is truer to the human impulse to create a material presence than the work produced by rigorously trained captives of the mainstream, whose work is mediated by establishment culture. Preferring Art Brut to “the art of museums, galleries, salons,” Dubuffet disparages the “cultural art” associated with professional intellectuals whose instinctive capacity for creating or appreciating art has been worn out like the seat of their pants from sitting too long in the lecture hall (Glimcher, 101) . Cultural art merely rearranges certain accepted ideas in public circulation, and never comes near to the primal “clairvoyance” by which organic, authentic art is hewn from the dross of experience.

A talk given in 1951 during a blinding, Chicago snowstorm enumerates Dubuffet’s deep suspicions about contemporary man’s faith in reason. Dubuffet skeptically dismisses ideas and language as being wholly useless to convey real experience, describing the former as “a lesser degree of the mental processes, a level on which the mental mechanisms are impoverished, a kind of outer crust formed by cooling” (Glimcher, 128) and criticizing language for its clumsy metaphors and awkward syntax that obscure instead of illuminating. No worthwhile art, Dubuffet lectures, originates from ideas or verbal descriptions, which are only the secondary markers of lived existence. Reality in the abridged, portable edition disinterests him.

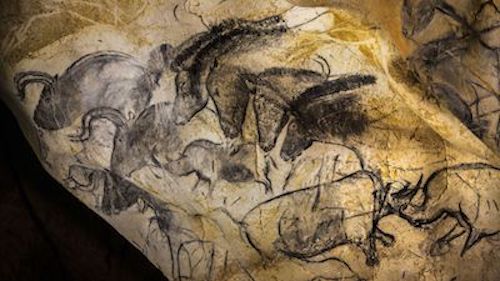

Unsurprisingly, Dubuffet champions human art that precedes written language at least by tens of thousands of years. Likely, the cave paintings of Chauvet and Lascaux even predate most spoken constructions of language. The artist speculated with his peers in Chicago, 70 years ago, about the influence of anthropological and art history assessments of “so-called primitive” painting and sculpture on a general trend to reevaluate the Occidental elevation of ideas and arguments over intuitive apprehension (Glimcher 127) . Werner Herzog’s 2010 documentary Cave of Forgotten Dreams makes it impossible to describe the art of Chauvet Cave as primitive in any regard. The film illustrates the sophistication of chroniclers of a time 50,000 years in the past, technically advanced in their abstraction of animal forms, expressive in their dramatization of movement and moment, resourceful in their utilization of available pigments and their incorporation of the contours of the cave walls in their depictions, and spiritually advanced in their understanding of the unity of man and nature. So a part of the world of gorges, forests, cave bears, lions, and rhinos were these early artists, they painted figures that combined the features of humans and animals, expressing their continuity. Dubuffet laments the Western elevation of reasoning over intuition and the divorce of civilized humanity from its animal identity.

makes it impossible to describe the art of Chauvet Cave as primitive in any regard. The film illustrates the sophistication of chroniclers of a time 50,000 years in the past, technically advanced in their abstraction of animal forms, expressive in their dramatization of movement and moment, resourceful in their utilization of available pigments and their incorporation of the contours of the cave walls in their depictions, and spiritually advanced in their understanding of the unity of man and nature. So a part of the world of gorges, forests, cave bears, lions, and rhinos were these early artists, they painted figures that combined the features of humans and animals, expressing their continuity. Dubuffet laments the Western elevation of reasoning over intuition and the divorce of civilized humanity from its animal identity.

We understand intuitively that language describes experience after the facts materialize; words don’t originate that which is real. Sartre divined his insight that being precedes essence and granted license to fellow Frenchman Dubuffet to discount the words we use to characterize the phenomena around us. That being stipulated, language and the artifacts it produces are not going to disappear. It can’t be observed or quantified, but the stream-of-consciousness narrating the life of every human must be inferred. Most of us are aware that our thoughts, fears, and obsessions have no true correspondence in the physical world, but apart from imposing chants, mantras, or pop culture slogans on the palimpsest of consciousness, who can turn off that running spigot for even ten seconds?

...

Samuel Beckett expresses his frustration with a reality conveyed by mere words in a 1937 letter to his friend Axel Kaun:

It is becoming more and more difficult, even senseless, for me to write an official English. And more and more my own language appears to me like a veil that must be torn apart in order to get at the things (or the Nothing-ness) behind it. Grammar and Style. To me they seem to have become as irrelevant as a Victorian bathing suit or the imperturbability of a true gentleman. A mask…Is there any reason why that terrible materiality of the word surface should not be capable of being dissolved? (Winkler)

Language exists indelibly in the environment outside and inside our heads. Beckett couldn’t exile consciousness, so he had to settle for the Nobel prize. That’s the thing about art: it’s futile, ridiculous, but it consoles.

Dubuffet’s advocacy for outsider art, or “Art Brut,” usefully expands awareness of the powerful expressions of the human condition that fall outside the narrow conventions of “cultural art”-- a board game, in which players trundle predefined tokens around an official path that rewards them with Monopoly money to calibrate the winners and losers.  Dispensing with the grid of language is Dubuffet’s own art, his l’Hourloupe people and fanciful, painted epoxy landscapes, springing up like mushrooms in public squares all over the world. He claimed he actually saw these forms, as William Blake told us he communed in person with anatomically correct angels, and Carlos Castaneda told us he saw the human form as a luminous, tentacled egg. More important than the assertion that Dubuffet’s work is free of the clumsy syntactic structures and metaphors of language is its realization of a uniquely individual view of what is real. We have an idiosyncratic system of ideas and metaphors in consciousness, hidden away from others struggling under the weight of their own delusions and fantasies, and as B.F. Skinner said, mentalisms mayn’t account for behavior or be empirically observable, but it sure would be interesting to get a glimpse of anyone’s inner life apart from our own.

Dispensing with the grid of language is Dubuffet’s own art, his l’Hourloupe people and fanciful, painted epoxy landscapes, springing up like mushrooms in public squares all over the world. He claimed he actually saw these forms, as William Blake told us he communed in person with anatomically correct angels, and Carlos Castaneda told us he saw the human form as a luminous, tentacled egg. More important than the assertion that Dubuffet’s work is free of the clumsy syntactic structures and metaphors of language is its realization of a uniquely individual view of what is real. We have an idiosyncratic system of ideas and metaphors in consciousness, hidden away from others struggling under the weight of their own delusions and fantasies, and as B.F. Skinner said, mentalisms mayn’t account for behavior or be empirically observable, but it sure would be interesting to get a glimpse of anyone’s inner life apart from our own.

In Dubuffet’s aesthetic, art should be valued for its freedom from false, logical constructs of reason and its nearness to man’s primal self, connected to nature. Instead, each of us carries within our organism a persistent landscape of memories, attractions, and aversions that only become more tangled and irreducible as life drags on. In a 2018 interview with Scientific American, Neuro-Philosopher Peter Carruthers proposed that the idea of conscious judgment and understanding is itself an illusion, that physical processes within the brain--perhaps simultaneously occurring within our entire body--are the seat of inferences, and our connections between reality and these purely physical processes remain unconscious, out of reach from the rambling voice in our head (Ayan) . Grappling with a premise in our internal dialogue is a reaction to an argument that has already been resolved elsewhere in our organism. Here’s the thing: isn’t it fair to say that a vast complex of hidden features and processes over which we can exert no influence and about which we have only second-hand understanding is much the same, in its mystery and dreadful aspect, as the external, natural world?

Art that pursues the unnameable aspects of individual character for the purpose of illumination and self-recognition disdains commercial or institutional success, yet these private revelations can be deeply moving to others. Especially, outsider art fascinates an audience with an appreciation for one of humanity’s great mysteries: Why do we compulsively cover the walls of our caves with vain mementos of our arbitrary (continued after caption)

An anonymous artist represented the Maryland State Penitentiary with a prominent ballfield in this whimsy bottle from a show at the Museum of American Folk Art.

existence? Henry Darger is perhaps the most notorious, completely untrained artist whose impulse to record his eccentric relationship to society was undeterred by his wretched isolation from it. I saw selections of his collage and watercolor fantasies of the fulsome “Vivian Girls in the Realm of the Unreal” when they were exhibited in ABCD: A Collection of Art Brut at the Museum of American Folk Art in 2001. Discovered after his death in a vast cache of 15,000 written pages and 300 illustrations, Darger’s work was shelved in the boarding house where he lived and worked and chronicles the fantastic, often violent, adventures of seven princesses of the Christian land of Abbieannia. The torture, suffocation, and imprisonment of these amorphously sexual little girls was a recurring motif in Darger’s sweetly deranged narrative. Clearly the reclusive artist and novelist was making concrete something deeply personal and probably deeply painful with his epic arrangements of cherubic female (and often hermaphroditic) children, whose appearance recalled paper cut-out dolls from Victorian-era nursery books.

Research and speculation about the life of Darger churns up the kinds of horrific details we are used to uncovering as a prelude or explanation to lurid crimes, not to a life of quiet, artistic exertion. His work has the scintillating allure of documentary evidence from a deluxe edition of Psychopathia Sexualis. Orphaned, abused, and sent to a state-run asylum for feeble-minded children, Darger eventually made his way to Chicago, where he worked for decades as a janitor in a Catholic hospital. Although the squalor of his childhood, long years of drudgery as an unskilled laborer, and social isolation make a dramatic background to the revelation of Darger’s monumental trove of creations, making one-to-one correspondences between those biographical details and his bizarre, almost certainly creepy catalog ignores the ultimately unanswerable question of why he was motivated to ceremoniously express the dark shadows of his inner life.

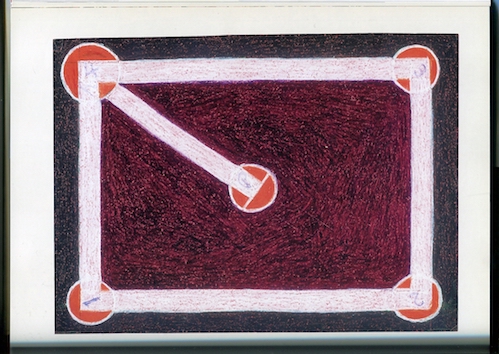

Undoubtedly, it isn’t Darger’s luridly febrile, fantasy enactment of his bleak personal history that audiences relate to, but the inexplicable courage motivating his expression of it. The catalogs of other outsider artists are far less baroque, yet still possess the dauntless passion to illustrate their psychic drama. In the American Museum of Folk Art’s Baseball exhibition, the work of psychiatric patient Eddie Arning, representing with a child’s crayon colors, slathered on paper, the familiar diamond of the infield, possesses a remarkably abstract minimalism. Arning reduces the various pleasures of boyhood encounters with an empty-lot pastime to a geometric simplicity, using the most available materials. The Reverend James Hampton, whose religious

visions fill a gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, spent decades amassing his Throne of the Third Heaven using silver and gold foil, cardboard, and tape. An inmate in the Baseball show placed in bottles wood slivers coated with model paints and made at least one museum-goer cry. Darger appropriated coloring books to express his alternate world of ambiguously sexual nymphs, and his resourcefulness connects him to Arning and the others as surely as the contrasting representation of details in their work distinguishes them.

visions fill a gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, spent decades amassing his Throne of the Third Heaven using silver and gold foil, cardboard, and tape. An inmate in the Baseball show placed in bottles wood slivers coated with model paints and made at least one museum-goer cry. Darger appropriated coloring books to express his alternate world of ambiguously sexual nymphs, and his resourcefulness connects him to Arning and the others as surely as the contrasting representation of details in their work distinguishes them.

Troves of priceless art have been found under the stained mattress of an institutional cell. But neither mental illness or a lack of sophistication identify the masters of Art Brut, whose exemplars, Dubuffet says, operate outside of the official, confining space of the academy and the world of commercial galleries. "Self-taught” isn’t synonymous with bumpkinhood. Autodidact has a more appropriate connotation to describe the maker of Thornton Dial’s tin-plate and driftwood marvels, or the earnestly simple, social commentary of Horace Pippin. As for the mentally unbalanced, Dubuffet remarks that “the mechanisms of artistic creation are exactly the same in their hands as in those of any supposedly normal person.” (Gilcher, 104) Importantly, formal reasoning isn’t a requirement for creating artistic expressions of the human condition. “Clairvoyance” is the qualifying characteristic of those who take the dingy commonplaces of their personal history and discover the means--however unsophisticated--to communicate them vibrantly to the world.  Whether we are talking about the prosaic scarves and hats of a Grandma Moses sledding hill or the pitched, feverish battles of Darger’s doll brigade with a godless cadre of sadistic Sourdoughs, insight divines the universal and recognizable attributes in the most extreme personal experience.

Whether we are talking about the prosaic scarves and hats of a Grandma Moses sledding hill or the pitched, feverish battles of Darger’s doll brigade with a godless cadre of sadistic Sourdoughs, insight divines the universal and recognizable attributes in the most extreme personal experience.

The recognition of the hand of the artist, I believe, is the paramount qualifying attribute of what we colloquially refer to as art. If I understand Dr. Carruthers correctly, judgments, perceptions, and the seeds of what will become obsessions accumulate in our bones, as it were, and an individual has no conscious access to these processes. That part of us which resides in the recording present relates with the same uncertainty or awe to that buried self as if it were implacable Nature herself. The artists in the limestone caves of France exerted a measure of control over a harsh environment, filled with predators and pitfalls, by mastering its forms within and upon the relatively civilized recesses of a canyon wall. Through a process we cannot perceive or truly comprehend, some persons are fated to slash their graffiti on the walls for the rest of us. The ultimate testament to their skill and technique is that we recognize the human qualities of their gestures across the chasm of tens of thousands of years, and across the divide between the sane and insane, free and imprisoned.

--October, 2020

Ayan, Steve, “There Is No Such Thing as Conscious Thought,” Scientific American, Springer Nature,

12/20/2018, www.scientificamerican.com/article/there-is-no-such-thing-as-conscious-thought/,

10/23/2020.

Borum, Jenifer P, ABCD: A Collection of Art Brut, 2001, Museum of American Folk Art, New York.

Gilcher, Marc, ed., Jean Dubuffet: Towards an Alternate Reality, Pace Publications, Inc.,New York, 1987.

Gôméz, Edward M., “The Sexual Ambiguity of Darger’s Vivien Girls,” Hyperallergic, Hyperallergic Media,

06/24/2017, https://hyperallergic.com/387178/the-sexual-ambiguity-of-henry-dargers-vivian-girls/,

10/23/2020.

Warren, Elizabeth V., The Perfect Game: America Looks at Baseball, American Folk Art Museum/Harry N.

Abrams, Inc., New York, 2003.

Winkler, Elizabeth, “Beckett’s Bilingual Oeuvre: Style, Sin, and the Psychology of Literary Influence,”

The Millions, Seth Dellon, www.themillions.com/2014/08/becketts-bilingual-oeuvre-style-sin-and-the-

psychology-of-literary-influence.html ,10/23/2020.