Tarantino Powers Fairy Tale with Alternating Current Between Story Frames

That new, epic poet in iambic pentameter everyone is reading describes how sometimes a generation contains so many overlaps of competing viewpoints and ideologies, a frustrated speaker resorts to irony to convey an utterance. Anonymous, perhaps you’ve heard of him , writes

For only rarely do words correspond

To the substance the writer based them on:

Speakers use them only because we must,

But never, ever are words worth full trust;

Consciousness of that gives us ironists,

Who stand two feet to left of what exists;

Both men and men's ages are prone to it,

The habit of speaking wryly and shit.

Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood (2019) negotiates the nature of its leading characters between different versions of themselves existing in various types of film, commercial, documentary, or dramatic. The purpose of the type constrains the portrait. A drama, for instance, intends a more complex and

ultimately unknowable version of its star than would a training film for clerks at an auto parts counter. In an advertisement, the trustworthiness of the pitchman is the only relevant quality. A showbiz-themed interview program poses softball questions to actor Rick Dalton and his stunt double Cliff Booth because the sole purpose of the segment is to promote an entertainment product. The interviewer’s un-ironic tone is reminiscent of a Disney wildlife adventure trailing a lost bear cub. Staged to resemble conversation, it is nothing more than a recitation of a press kit, but the absence implies a presence: the actual problems of the actor and his stunt double that are a focus of Tarantino’s story.

ultimately unknowable version of its star than would a training film for clerks at an auto parts counter. In an advertisement, the trustworthiness of the pitchman is the only relevant quality. A showbiz-themed interview program poses softball questions to actor Rick Dalton and his stunt double Cliff Booth because the sole purpose of the segment is to promote an entertainment product. The interviewer’s un-ironic tone is reminiscent of a Disney wildlife adventure trailing a lost bear cub. Staged to resemble conversation, it is nothing more than a recitation of a press kit, but the absence implies a presence: the actual problems of the actor and his stunt double that are a focus of Tarantino’s story.

In a sort of epilogue to the movie, a black and white cigarette commercial with a catchy jingle features Rick Dalton hyping the made-up brand Red Apple. Let me give it to you straight. It’s a smooth smoke. As with Lost in Translation (2003), the insincerity of the actor delivering the pitch goes without saying. Alternately, the depiction in the movie’s primary thread of Rick’s excessive drinking and smoking, increasingly listless acting, and declining career is completely convincing. The cheesiness of Dalton’s strictly commercial performances invite us to see them as evidence of his eroding professional standing and definitely not as endorsements for Tarantino’s favorite mythical brand of smokes.

Segments we see of Rick's TV series show how formulaic are its stories, and his tough-as-steak performance of kill-happy Jake Cahill surprises no one. Outnumbered in a gunfight, he kills five bad ducks all lined up like Donald's nephews before they can get off a shot. They had an ambush in last week's episode, too, but that was entirely different: in that one, there were four guys. Not that Tarantino thinks all 60s television was lame. Cliff watches some Mannix, and it's terrific. The lameness of the show that is the highlight of Rick's acting career develops our understanding of Dalton's falling star. DiCaprio plays the character as desperate to hang on to his fading relevance and willing to take undistinguished roles as a result. While authentic interaction between them reveals the nature of his characters, Tarantino also uses a counterpoint: mock commercials and old kinescopes starring an uninvested and fading actor are played against a version of his life that by the conventions of movies is the real one.

Less successful at using contrasting filmmaking purposes to reveal character is Kurt Russell’s narration of the backstory behind Cliff’s damaged stunt career: Booth participated in five minutes of grab-ass that banged up both Bruce Lee and a muscle car from The Green Hornet set, and Kurt Russell plays his pissed off stunt co-ordinator and the offscreen voice who embellishes Cliff's scenes. The first time we hear him as narrator, he says two lines, calling out a lie in Rick Dalton's dialogue, and the effect is jarring. For one thing, The information he adds could have easily been revealed without violating a basic rule: don't tell, show. But more important, it's one thing to counterpoint the life of a flawed actor with his onscreen puffery, but it's another thing to give the job of narrating Cliff Booth's official Hollywood story to a guy who hates "the creepy wife killer" as much as anyone.

The point of origin of Kurt Russell's narration isn’t clear. We can’t know from what time it comes, or what authority the speaker has to be both a participant in and narrator of the dark and funny day that was a turning point in Cliff’s career, a day as critical to his story as the time he killed his wife with a harpoon gun. We do know Tarantino loves to put actors in his movies whose signature roles are not critically acclaimed. He likes the ironic friction between the actor’s well known, lightweight roles and a grittier part in an art-type film; however, Russell’s narration of a crucial event outside of the ‘present’ narrative creates friction that doesn’t work so well as the discord between other plays within the play, and it probably should have been excluded despite Tarantino’s enthusiasm for Kurt Russell’s performances as Snake Plissken and the computer who wore tennis shoes (in 1969, the year in which ..Hollywood is set).

Often, audiences complain about the ridiculous, fairy tale improbability of the movie industry's product. Beginning with its title, Once Upon a Time in…Hollywood lets us know the planned-to-the-last-gaffer escapism movies craft is the subject of this one, not movies' imitation of reality. Tarantino’s love letter to L.A. is set in 1969, when some say the Sharon Tate/Manson cult murders in the Hollywood Hills fragmented Woodstock's peace and love and welcomed in the senseless violence of Altamont. Tarantino imagines how a few, deft karate chops in the right place could have saved the day. His is the comic book lover's game of “What if..?” What if the Manson cult meets Brad Pitt? Sharon Tate and Jay Sebring’s sadistic killers go to the wrong house, and it’s occupied by a cool, calm, and deadly Hollywood stuntman! Aside from Manson’s disciples, the movie’s characters are all industry people; indeed, every component of the film celebrates movies and the city where they are made. Our Cinerama camera wide-screens everything to its best version. With movie-making savvy at their disposal and a tradition of turning ordinary disasters into happily ever afters, count on Hollywood professionals to keep the monsters away!

Of all the miraculous powers of the movie studios, Once Upon a Time in…Hollywood spotlights the ability of set and production designers to meticulously recreate dozens of long gone venues and storefronts all over town. If loads of capital and veteran film crews and artists can restore four blocks of Hollywood Boulevard to its 60s heyday, why can’t a motion picture bring back the people we lost: Sharon Tate, the sweet and sexy starlet, and Jay Sebring, Steve McQueen's best friend and the inventor of hairstyling?

A restoration of the Cinerama theater created for Once Upon a Time in...Hollywood. The original was built in 1963 on Sunset Boulevard specifically to introduce the widescreen Cinerama process. Before film fetishist Tarantino revived it for Hateful Eight in 2015 at a cost of tens of millions ($80,000 alone to install special projectors in every theater that ran it), the last US movie filmed in Cinerama was Krakatoa, East of Java (1969).

Fun Fact: Krakatoa was west of Java.

I'm sure Tarantino's pitch for his movie to Columbia Studios included the absolute necessity of restoring to its glory every eatery and landmark–including the Pussycat Theater–in the heart of town. Roll in on trailers every available-to-rent, restored classic 60s autos in the data base, and stage a lineup of beach-ready Fisher bodies the likes of which we will never see again! Hollywood professionals wield the neon aura of Los Angeles to create life from the dust, and it was the godlike powers of set builders and prop procurers that Tarantino wrote a leading part for in his script.

Meta-movies such as Richard Rush’s The Stunt Man (1980) make a game out of turning expectations on their head, resulting in works that declare the process of making movies to be ruthlessly anti-reality. A stuntman, we learn, is one of the members of the crew who best implements a movie’s disentanglement from physical and behavioral rules of conduct. (Coincidentally, the titular character in The Stunt Man was portrayed by Steve Railsback, who played Charles Manson in the TV miniseries Helter Skelter (1976).) In the Tarantino work, Bounty Law actor Rick Dalton has two, real-life physical skills: firing a flame thrower and falling off a horse. For everything else, his stand-in Cliff takes the hit. It will be Cliff inside his house, not Rick, when the Manson killers crash, Cliff who gets seriously wounded, and it will be Cliff’s life, not Rick’s, that changes forever after Dalton marries. By making a stunt man a leading character, the screenwriter reminds the audience Hollywood rules say a guy can make it through a shitstorm safely if he has a stand-in wherever he goes. Why take the risk one place is enough when being in two places at once is safer?

Tarantino incorporates another dominant fact about late-60s filmmaking into his tale. The old studio system was dying and a new era of independent films and actors took over. In the movie, Roman Polanski personifies the different kind of director, an auteur, not some studio hack. Along with the creative types infusing the form  comes their new ways of looking at movie tropes. The conventional Western hero gives way to the anti-hero of the Spaghetti Western, exemplified by the character of Harmonica in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). This anti-hero wears the duster of mystery, and he’s cold-blooded and ungallant, not like Rick Dalton’s teeth-gleaming, preening bounty hunter in the NBC-TV oater, whose entire backstory the host of an Entertainment Tonight-type program delivers before the opening credits are done.

comes their new ways of looking at movie tropes. The conventional Western hero gives way to the anti-hero of the Spaghetti Western, exemplified by the character of Harmonica in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). This anti-hero wears the duster of mystery, and he’s cold-blooded and ungallant, not like Rick Dalton’s teeth-gleaming, preening bounty hunter in the NBC-TV oater, whose entire backstory the host of an Entertainment Tonight-type program delivers before the opening credits are done.

Artistic freedom comes first in the new Hollywood. Corporate and by-the-book is the old style, thus Paul Revere and the Raiders are groovy, but Jim Morrison is far out. The Spaghetti Western, as Rick’s agent informs him, is a refuge for stars of the old regime who are past their leading-man prime in the corporate system. A refuge if they can act. Leone expanded the careers of Henry Fonda and Jason Robards because they delivered credible performances as murky criminals. As we’ve said, Tarantino has repurposed many actors from fondly remembered series TV in his multi-layered catalog. We don’t know if Rick can cut it. He lacks focus, and the hard life of cigarettes and booze is taking its toll. His story in the movie is whether he can summon the acting craft and professionalism of his eight-year-old co-star in Lancer, who must be addressed on the set by her character's name, “Marabella” .

We see an imaginary screen test of Rick auditioning for the role of Captain Hilts, the Cooler King, in The Great Escape (1963). It’s Steve McQueen’s classic part, and in the screen test, which we know didn’t actually happen in front of John Sturges, we are going to see the best Rick, right? his ideal performance. We see it. and he’s...fine. Rick can make a frowny face at the Nazis, but even Harpo can look like a tough guy. You-a give-a him a plenty money, he get-a plenty tough. Lacking the cool of McQueen or the stillness of Charles Bronson, he resorts to hollow intonations, never fully engaging with the character. Compared side-by-side to McQueen, Rick shows why Steve and Charlie made The Great Escape, and he got The 14 Fists of McCluskey.

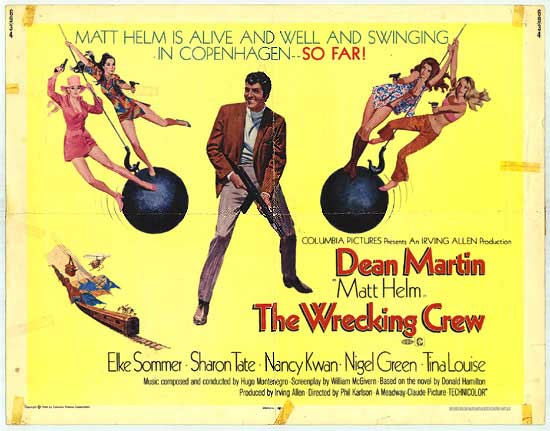

The cloaked anti-hero is as essential to the new cinema as the drink-in-hand smarminess of Matt Helm in The Wrecking Crew (1968) was essential to Dean Martin and his bosses on the Columbia lot. Tarantino's movie uses two intact segments from the original, the lunatic inclusions of a relentless pop culture addict. Dino's lurid ogling, effortless line reading and phony action scenes don't play so well fifty years later, unless you're a child of the 60s, where all things spy-related were swoon-inducing, and Dino (only groovy, not far out) was the smoothest at half-singing double entendres to dreamy co-stars like Elke Sommer and Sharon Tate. In the same swinging style, Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood shows a segment of Rick guest starring on the actual 60s pop chart show Hullabaloo, doing his smarmiest Dean Martin impersonation accompanied by a quartet of go-go-booted colleens. His fairly awful song is an extended double entendre, anachronistically referring to the blue movie classic Behind the Green Door for yucks.

Tarantino presents the Swinging Sixties with the devotion of Andy Warhol. While dirty Hippies are derided  in the film explicitly and by implication, it is true the mainstream pop culture of Dean Martin, C.C. and Company, and Playboy Mansion was characterized by a swinging lifestyle distilled from the peace-and-free-love communism of the counterculture. In a huge Mansion party scene complete with ski slope-long tracking shots, Steve McQueen, Michelle Phillips, Mama Cass, and Sharon Tate drop by. Mini skirts shimmy. There’s Bunnies! Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood painstakingly recreates the music, style, and decadence of an era for which the director is keenly nostalgic.

in the film explicitly and by implication, it is true the mainstream pop culture of Dean Martin, C.C. and Company, and Playboy Mansion was characterized by a swinging lifestyle distilled from the peace-and-free-love communism of the counterculture. In a huge Mansion party scene complete with ski slope-long tracking shots, Steve McQueen, Michelle Phillips, Mama Cass, and Sharon Tate drop by. Mini skirts shimmy. There’s Bunnies! Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood painstakingly recreates the music, style, and decadence of an era for which the director is keenly nostalgic.

Although it is often critically derided as a reason to make a movie, nostalgia recalls a time when Pop was experienced communally. The Green Hornet was a shared experience of kids all over the block, and always at the same Bat-Time, Bat-Station. No such central disseminator of cultural phenomena as the Hollywood factory for movies and television persists into the current century. Where is the capital of the Internet? We don’t even have record albums. Go to your local Quizzo on a Tuesday in Philadelphia, and half of the questions are about songs and movies of which only a slim percentage of the barroom will have ever heard, and the right answer in the other half is more likely Joaquin Phoenix than Jack Nicholas. Caesar Romero? That's a sportscar isn't it?

Ironically, Tarantino’s nostalgia for the old days of the Hollywood formula is contrary to the postmodern cinema of which he is one of the most recognized progenitors. He works a side of the street where forms are turned upside down and conventional movie storytelling burned to the ground. Since there’s a form of power that harnesses the thermal contrast between the icy water at the bottom of the lake and the warm water at the top, it’s fair to say Tarantino harnesses the differences between cinematic genres and powers his pictures with that. Styles and genres aren’t even available to the mind without thinking nostalgically; that is, unless one has the know-how to frame a proper trivia question using one of those Venn diagrams, with a huge "facts" circle and inside that a subset labeled "in regular use," words like “Western,” “Disney,” and “buddy movie” are random gibberish.

The most pervasive trope in Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood is the fairy tale, the Disney version and the general Hollywood kind. Sharon Tate and her murder are central to this theme. At Cannes, Tarantino got heat from a reporter for not giving Margot Robbie’s character enough lines, and the director tersely refused to answer the question. His leading lady is literally barefoot and pregnant in this film. What was he supposed to say? The movie isn't about Sharon Tate as a physical person. She is a fairy princess, a movie starlet living the dream. It would be unchivalrous to give ordinary human utterances to or speculate on the private life of a screen goddess. Tarantino is struck by the actor's goodness and incandescence. The ultimate fan, he gets to play with Columbia’s money and their film library. At a commercial showing of The Wrecking Crew, Margot Robbie's Sharon watches herself on the movie screen, bare feet dangling while closely attending the audience's favorable responses, a perfect starstruck ingenue. Tarantino doesn’t use the seductive dance Sharon does for Dean Martin's alter ego Matt Helm, but he does screen the actress falling on top of him. Double entendres ensue. In The Wrecking Crew, Tate is achingly beautiful; we hope nothing bad ever happens to her.

In the once-upon-a-time, Hollywood fairy tale, the good guys come to the rescue of a damsel in distress. Sergio Leone's movie features the same plot in a Western version. Tarantino's nod to his auteur predecessor contrives that authentic tough guy Cliff Booth happens to be in the Polanski “gate house” just as the Manson-family dragon invades. In the rousing fight scene that follows, we learn two important lessons: a well-trained dog is the responsibility of every dog owner, and three hours-a-day practicing your instrument is a good investment. The climactic showdown is right out of the grindhouse revenge genre, a kind of film Tarantino has himself made. The Mansonites aren’t just killed, they’re exterminated, like the rats that flavor Brandy the pitbull’s dog food. It’s a revenge movie for something that hasn’t happened yet! The doubled prince saves the day, and he is invited by an angelic voice coming through a speaker up to the castle for drinks. Fairy tales are also transformation tales, and in this one, Rick Dalton, having transformed his acting career and slayed the dragon, passes through the guarded gates from the old Hollywood to the holy sanctuary of the new.

The substance of Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood is the friction between alternate styles and movie genres and irony is its pervasive tone. The buddy movie (including movies where a masked hero like the Lone Ranger or Cato has an ordinary alter ego) is one of the genres Quentin Tarantino mines to create a complex surface conveying an epic story, a “What If?” the 60s never died kind of thing. The complaint that it is revisionist, while literally true, is figuratively irrelevant. As we learned in 2019 from Avengers: Endgame, changing the past is impossible: the thing won't budge. But with our high tech know-how and Hollywood sagacity we can alter our own present. Screenwriter Tarantino had at his disposal a poorly understood technology that redeems the present by transporting his audience to a time before tragedy occurred: it’s called the past tense.

Drew Zimmerman, 2024