Jim Strong's "Transcribing the Wilderness"

“Working on mysteries without any clues..” –Bob Seger

“Something is happening, but you don’t know what it is.” –Bob Dylan

Jim Strong’s March 2023 show at Vox Populi Gallery dashes to the curb the vain, human hope of penetrating the mysteries of our existence. The accompanying statement for the installation tells us what to expect beforehand:

Transcribing a Wilderness is a practice of listening in tongues, combing everyday streams of information for hidden manifestos in misremembered bits of conversation, typos, scrambled notes, fragments of paranoid dreams and hallucinations.

The description of the show lists notoriously ambiguous or meaningless bits of evidence, but in fact, every human utterance is merely metaphorical, and even the most eloquent expression never gets us closer to whatever the hell the subject is.

Socrates said it, though it took him twenty or so conversations to finally blurt it out: “I know nothing, but at least I know that.”

Socrates said it, though it took him twenty or so conversations to finally blurt it out: “I know nothing, but at least I know that.”

Language is a hopelessly clumsy means to make sense of man’s earthly predicament, but so is every other symbolic language. “Abstract Art” is redundant. An image on canvas or sculpted in marble is no more what it intends to describe than “a summer’s day” adequately conveys the object of Shakespeare’s love (and in “Sonnet 18” the supreme master of English admits this with evident frustration.) The starting point of classical abstraction was “art for art’s sake,” a creation that doesn’t suggest or stand for anything other than what it materially is. Works by de Kooning or Calder use pure form as their subject, the gestural language of a brushstroke or the untranslatable effects of primary color on sheet metal curves and discs. Not worthy of mention are the frantic daubs and doodles local paint-and-sketch-club bastardizers of abstraction title after a random Vivaldi symphony or a day at the beach. Strong’s work makes abstractions of fragments of language that, while recognizable as human speech, are profoundly impenetrable, and that seems to be the point. It is what it is.

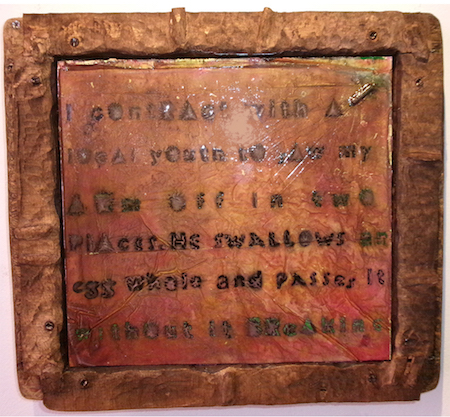

Along one side of the gallery are heavily lacquered, textual fragments in conspicuously hand made frames. The worn out wood salvage, solidly screwed together, intently tries to make something out of an indecipherable nothing, like Tony Stark trying to save his life by inventing Iron Man from scrap metal in a cave. The stenciled lettering on heavy paper or cloth,

If David Lynch has a sampler hanging in his living room, it might say something like, “I contrast with a local youth to saw my arm off in two places. He swallows an egg whole and passes it without it breaking.” Another of Strong’s relics has Dr. Seuss-y looking whozits illustrating the text “Tied down with pheromone hair.” What can be made of these? The point is they refer to an empty cardboard box (pardon my metaphor). It’s a nothing presented with great human effort and momentous solemnity, like Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason or Wittgenstein’s Tractatus. Transcribing a wilderness with the crude tools at hand and makeshift language is meaningful only insofar as it gives us something to do: Grandma embroidered “Idle Hands are the Devil’s Workshop” and put her homily in a frame and hung it on the wall, too.

Opposite his yellowed, broken language Legos, Strong presents what could be their antidote: a series of stained glass windows, six-foot tall celebrations of light and color. They aren’t formal, churchly expressions of holy majesty, not pieced together with leaded strips or painted with the language of an Academic brush, but their idiosyncratic references to the natural world–fanciful plant and animal silhouettes–remind us that Creation, though it exceeds our critical understanding, nevertheless exists. Ultimately, our “network time killers” (to borrow a David Letterman expression from before he looked like one of the coughdrop Smith Brothers) to express the phenomenon of nature are inadequate, but we know at least that our lives exist in its loving embrace.

Transcribing the Wilderness surely is as immune to critical language as the extra-dimensional realities it nudges the visitor to contemplate. Strong produces one image, however, representing a clear-cut metaphor for the vanity of interpreting the ineffable. Let me take advantage of its accessibility to put it into words: on the border between the wall of lacquered fragments of tortured sentences and the colored effusions of light, he positions the semblance of a ticker tape machine, that device merchants of the material world use to calibrate the current market value of goods and man hours. As a means of explaining the true nature of human existence, such a machine, while connected to data coming in from all over the globe, describes our real life no better than the “Breaking News” reports from Forbes that interrupt my Internet surfing reveal meaningful events in the chronicles of mankind. Strong’s machine, suggested with a few, simple pieces of wood and a “found” bell jar, spews a long, meandering coil of ticker tape. The white strip has nothing written on it.

©Drew Zimmerman, 2024