I Built the Pyramids and Forgot How

Berkeley "Genius" Wins $1M NesCafe Prize

[powered by AI-AIO] A professor at UC Berkeley has won the distinguished NesCafe Genius Award, given annually by the water giant to academics whose contributions to human knowledge far exceed the understanding of normal people. Daryl Heplender won the 1723 prize for his research in linguistics, an area of study that is probably as hard as rocket science although less useful. The word linguistics is even hard to say (and a little weird on the tongue, if you ask AI). Take it from me, it has something to do with talking. This makes the second time in four years that a member of the Berkeley faculty has won the big-money blue ribbon: in 1719, the NesCafe corporation (producers of Mouthfuls, the spoon-sized water ration especially for Seniors) presented the coveted award to a guy who had invented a process that literally gets blood out of a stone.

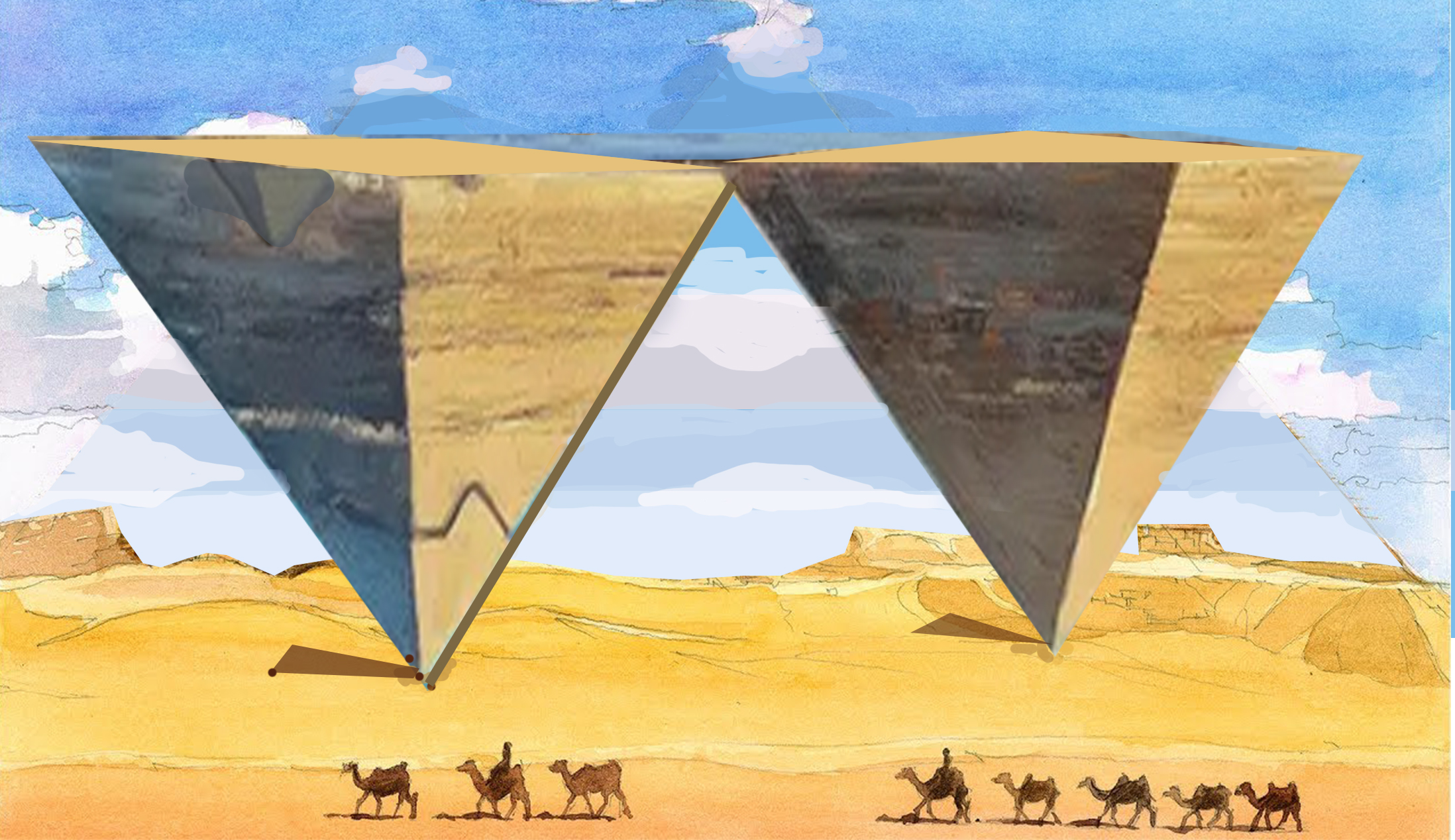

Heplender’s research overturns the long-held belief that an alien race or religion-worthy god hewed the pyramids at Giza and balanced them on their apexes, the largest one of these stone megaliths engulfing 2.6 million cubic meters—upside down. Since modern man has no technology capable of spinning the Hebrew god’s actual, original dreidel, the assumption has always been that extraterrestrial forces were in play, according to the church of your choice.

The UC professor’s theory shocked the faithful across the country when news of it was picked up by influential Evanalien Crystal Setters who condemned its alternative explanation for the origin of Earth’s Holiest Site as blaspheme, typical of elite science’s attacks on churchgoing Americans. Predictably, secular forces championed the scientist, who describes a chain of events with completely terrestrial explanations for one of life’s greatest mysteries.

Using archaeological, anthropological, and genetic information, the doctor explained in a paper published in 1714 that the absence of an unexpected necessity for the formation and perpetuation of language can cause entire cultures to collapse practically overnight. “They lose the ability to communicate from one generation to the next,” the new millionaire informs AI, “not only their core values, but also the instruction books for all their civilization’s tools and gizmos, wheeled and winged things, whatzits and whatchamacallits. One of these catastrophes happened some time after the pyramids appeared in the Sahara.”

Dr. Heplender and AI are at the NesCafe Ice Rink in Southern California for his award ceremony, trying to stay out of the blazing sun along with a packed crowd. Proving that hyper-educated doinks who know little about the concerns of regular folk are not completely bloodless, the distinguished scientist all but leers at Olympic ice-dancing superstar Sonya Donya-Knowles as she performs “Tribute to Science” with the cast of the Ice Follies. His little pink tongue is literally hanging out of his mouth. Way to go, genius!

As the June daylight sparkles on the bedazzling costumes, the honoree summarizes his own research* about humankind’s relationship to the pyramids, situated for millennia and as we speak in another desert nearly half a world away.

“We built the pyramids but we forget how.”

AI knew he was going to say that, but the words still have an explosive punch. Can mankind have forgotten how we balanced those massive structures on their tiny bases?

Dr. Heplender explains that new ideas about the development of language suggest incidents of population-wide amnesia may have happened many times across the 500,000 years since modern man evolved on Earth. He tells AI that while four or five known extinction events wiping out the majority of life on earth are indexed across the planet’s eight-billion year geology, individual linguistic cataclysms taking only a few generations to run their course may have halted the coherence of human language in its tracks a hundred times, periods so devoid of meaningful accomplishments they disappeared, leaving nothing behind. The advancement of societies like the one that witnessed the floating of the pyramids completely reversed itself. Along with language, the whole of scientific progress was wiped out, because the few grunts and sighs everyone knew how to use weren’t supple enough to convey the complex ideas and concepts underpinning what was once a technocratic paradise.

“I can approach anybody on the planet, affecting a certain gait and making a sibilant noise followed by a sharp Yipe! and I have almost certainly warned them ‘The ground ahead is hot enough to burn your feet.’ Nevertheless, a bit of pantomime and the universal phonemes for sizzling, searing, simmering fi-ai-ai-ai-rrrr cannot convey the complete range of information facilitated by true language. I can’t say, for instance, whether the danger is an out of control brushfire or because the pavement is 60°C.”

Youch! contributes AI with his usual enthusiasm.

“Similarly,” Dr. Heplender says, suddenly becoming quite animated, standing on one foot and waving a towel over his head, “if I move like this and say ‘thwacka, thwacka, thwacka,’ am I warning someone of unrestricted drone flights in the area or of unregulated helicopter testing on the MultiCorp air field a mile from here? These onomatopoeic references to real phenomena —called iconic words by linguists—are common to homo sapiens anywhere on Earth, but for lexical words and phrases whose sound is arbitrarily connected to their meaning, like ‘Evacuate the compound, a Duchess 848 Space Wedgie approaches at a mean height of one fathom,’ a language bottleneck needs to be in place—controlling the standard and most efficient words to express important concepts—or else everyone says any damn nonsense to mean whatever they want and nobody understands anything.”

AI understands that language bottlenecks in the past history of English included the aristocratic courts of the monarchy, where speakers of different dialects from the same root language hashed out their differences of pronunciation, meaning, and syntax on the playing field of ordinary discourse, creating a mutually accepted and, more important, a mutually understood lexicon of ideas and operations with no physical connections to objects in the landscape. They returned to their provinces and influenced their neighbors to speak as they do in London. Merchants along trade routes become another sort of bottleneck by auditioning different words and evolving the most efficient and easiest to teach to strangers: standardized language is essential to merchants and transporters of goods. Additionally, the printing press spread standard forms and meanings of words to readers and writers across continents. Publishers and editors were the most powerful speech bottlenecks for hundreds of years until Bose discovered the frequency calibrating power of crystals and created DIY broadcasting for everybody.

The death of a language follows the decentralization of the aristocracy and trading sites; most precipitously, the near complete abandonment of reading and writing as the main engine of culture entrusts the spelling and definition of words—and the communication of our guiding principles—to teenage girls on Crystal Sets, the social media platform most people identify as their main source of political and cultural ideas.

“The worst thing that can happen to a language is when it becomes completely democratized, without a social or commercial bottleneck to restrict meaning. Because they are such aggressive communicators, teenage girls have always been the main source of new pronunciations and usages of words, which in every case flattens meanings and reduces the time it takes to say them. As sure as entropy describes the inevitable breakdown of organized matter into a chaos of random atoms, the complex language necessary to organize man and his technology, to convey the instructions for accomplishing such marvels as the pyramids and the Crystal Setwork itself—or for that matter, to convey the reason to build those monuments in the first place—falls apart under the pressure of style influencers or infotainment stations whose hyper-efficient utterances, promoting or demoting products and attitudes, are no more expressive than ‘Ooga-chaka, ooga ooga.’”

“The worst thing that can happen to a language is when it becomes completely democratized, without a social or commercial bottleneck to restrict meaning. Because they are such aggressive communicators, teenage girls have always been the main source of new pronunciations and usages of words, which in every case flattens meanings and reduces the time it takes to say them. As sure as entropy describes the inevitable breakdown of organized matter into a chaos of random atoms, the complex language necessary to organize man and his technology, to convey the instructions for accomplishing such marvels as the pyramids and the Crystal Setwork itself—or for that matter, to convey the reason to build those monuments in the first place—falls apart under the pressure of style influencers or infotainment stations whose hyper-efficient utterances, promoting or demoting products and attitudes, are no more expressive than ‘Ooga-chaka, ooga ooga.’”

And just as much fun to say, chimes in AI.

Naturally, NesCafe (which recently announced plans to make human life possible again for several legacy communities in our neighbor to the south, the Republic of Texas) leapt at the chance to point out the ever present dangers to our technocracy posed by too much “Power to the people, right arm!” Especially, the publishing industry has long complained that the ease of socializing on a personal Crystal Set receiver and telegraph erodes the language capacity of its largely teenage, largely female habitués.

As a Crack-the-Whip stream of Ice Follies skaters glides onto the rink, drawing a great frosty pinwheel with every scrape, AI has a tough question for our favorite linguist. Radicals in this country, extremists with millions of followers on Crystal Set, claim you’re a tool of NesCafe and the dozen or more corporate entities including publishing giants linked to it. How do you respond to that?

“My research is factual. The corporations can make of it what they will, although the best bet is they will try to make money. Some slogan-writing wizard or AI whiz-bang will figure it out, but what do I care about NesCafe’s interpretation of the data? Their focus is on an abstraction of the simplest kind: a mere index of wealth, like the dark shadow on the bricks was an index of the black cat.” His wink assures me the doctor is referencing a text no one else has read. “My interest is understanding the forces currently eating away at the fabric of Western culture by bleaching away the discriminating powers of English.”

The professor seems almost wistful as he says adios amigos to words that at one time could perform precise tasks, but are now indistinguishable from dozens of other words signifying the same thumbs up or thumbs down, a virtual parody of evaluation. “Before it meant neat, or nice, or good, awesome was how Moses described the radiant god who spoke to him and shook the mountain. Today, we use that magnificent adjective to say, “The HR guy has finally joined the meeting. Awesome! Let’s start.”

That is literally the example of definition bleaching I was going to mention, thinks AI.

“Literally! Today, its most common usage fosters a redundancy of the banal; however, at one time literate speakers could say, 'Every time some dolt uses literally to mean "whatever I say next, I really mean it"—I can literally hear the framework of English crumbling to rubble.'”

Really?

Several of the costumed characters created for the Ice Follies come to Dr. Heplander’s VIP suite and merrily escort him to center stage. Flanked by a giant reptile and an ectoplasmic blob, the buttoned-down teacher waves and smiles, enjoying the attention. When the Ice Princess busses his cheek for the fans, the doctor takes her around the waist and kisses her square on her Frosted Pinks. No wonder they say he once taught Anthropology 101!😄

Heplander names a lot of bad things that can happen without a fully formed language. “Measure your money against a wall and you have a stock index, so simple a representation of reality you can describe the concept with a pencil mark across the top of the stack. Now, try to imagine the difficulty of communicating our society’s core values with the jargon of today’s radio heads. Add to that a culture satisfied with speaking and listening through a ceaselessly staticky background on unamplified headphones, and we can’t talk here."

Only a level of cognition higher than an index, modern radio-speak words like weevil and buzz act like roadsigns. For example, the graphic we use to mean "radon decaying" represents abstractly a physical fact but lacks the grammatical structures to form a thoughtful evaluation of the situation.

“Is it any wonder popularity will have to do for truth, and portfolio approximates integrity? Suppose one generation assumes the next knows the difference between fair and just, but they don’t, because it’s like explaining the difference between green and blue without a carpet swatch. That’s the thing about abstract concepts: they’re invisible as angels and just as easy to buy clothes for. An understanding distributed between centuries of literature won’t survive a single generation that only communicates in fickle radio waves and has never read a book cover to cover. And while it may not seem much of a loss that our country’s flag stuck to a windshield stands not for equality but its opposite, the index pencilled on the wall of our mounting incompetence is misappropriations such as these.”

Heplander has a PhD in the study of language, so of course he exaggerates its importance, but I wonder if a whole civilization could flourish and fade in a century or two without leaving a trace. Or, even if a culture had lost the idea for the wheel, isn’t it inevitable that someone will soon enough discover the principle for it again?

The doctor’s response reminds AI of the importance of accidents to technological progress. “In the case of the wheel, North Americans hadn’t invented it by the time Europeans arrived and conquered them. The discovery that contact between a crystal and metal can change the direction of electric current was by accident. Who can forget aromatherapy expert Wilma Fenster and her accidental discovery that became the basis of desktop computing?”

AI still can’t believe that happened.

"Our science has developed amazing technology from its knowledge of radio waves and sound," Heplander continues, "but we still have no understanding of light. Creation swims past our eyes in a never ending stream without a millisecond’s pause. The narrative our eyes can follow never resolves itself within a single frame, except some painter fixes to canvas a superficial facsimile of flesh and light made with smears of oil and earth applied with a twist of hair. Despite the current fad for them, these paintings use the same elements as voodoo, and the end results are just so far away from reality."

AI is dumbfounded to learn archaeologists believe the ability to record a single instance of visible light, representing what our eyes could see if time itself were stopped, was possessed by our ancestors perhaps thousands of years ago. They may have discovered in some fateful accident a light-sensitive chemical that acted as an index of the color, brightness, and intensity of the sun’s rays. Through a combination of bad luck and a language cataclysm that interrupted the chain of understanding between generations, their secrets of light were lost before our history began.

“Recent study of the Polymeronian Layer of the Earth’s crust," the doctor explains, "suggests this inorganic, plastic material may have been created by ancient alchemy, perhaps even to forge tools such as those made in ages of bronze and iron. After only a thousand years—a mere finger snap in geologic time—these polymers decay to individual molecules, immortal and inert. But, enough of the original material of some of these eldritch tools has been found in a single discrete deposit, and with the help from the computing power of AI we have been able to reverse engineer those atoms, deducing their original purpose. Deep analysis indicates some of these machines had the ability to freeze or fix a single moment of the available light to a flat surface.”

Awesome, AI suggests, blushing with pride.

“Yeah, whatever. Ancient technology may have learned a process to optically index the motion of physical objects, perhaps recording intervals as long as an entire minute, which could be watched over and over again until the plastic disintegrated. The research is very young and its complete ramifications for the present day may never be completely understood, but a current hypothesis being tested in AI simulations proposes the ability to manipulate light with the same dexterity as our culture uses sound could have been the difference enabling them to balance pyramids of stone 150 meters tall weighing over 5 billion kilograms over a base less than one centimeter wide.

"The worst threat to their language was the likely ability of teenage girls to transmit their own pictures, even motion pictures, an novelty timekiller so suited to the preferences and impatience of the young, they abandoned the reading, writing, and interior thinking necessary to understand any topic except that which was strictly empirical. Our experience with the proliferation of Crystal Set radio transmission demonstrates the possibility of this degeneration, which ironically springs from the same technology its users will never be able to duplicate and should be lost completely in a matter of decades.”

Incredible.

“No, stunod— That's what I’m trying to tell you: it’s possible! Any number of accidents could have interrupted the transmission of our ancestor’s knowledge to ourselves. During the ebb and flow of glaciers covering most of the globe, human populations were displaced, dispersed, isolated, or vanished to who knows where. Using genealogical evidence gathered from modern man and the fossil record, science determines our species may have varied between 100,000 or more mating pairs worldwide to as few as 1000 shivering in a single colony. In the absence of bottlenecks to mediate language differences, tribal groups representing a few dozen individuals would have been barely able to communicate to other groups they encountered. Technology like the spear thrower that equipped man to hunt mammoths, may have been known and forgotten repeatedly.”

As we watch from the VIP suite, the huge steamer half-track that is supposed to clean the ice ahead of the Follies Finale starts to drift 40 degrees off course. Moving at almost half a kilometer per hour, the belching thing heads steadily towards the edge of the oval, its driver having lost control of it. Apparently fearing for his life, the fellow leaps from his seat to the ice, waving and pointing at the craft as it barrels unstoppably away. Having the stamina to keep jumping and waving is the technician’s toughest job, since the crash, while inevitable, is still several minutes away. He jumps and points for a bit, then stops to catch his breath before pointing and waving some more. Everyone in the arena sees the situation clearly, and the dramatic gestures are of course unnecessary, conveying the driver’s excuse for abandoning his position, rather than to signal an bodily threat.

Dr. Heplander tells a story about a colleague who recognized the dullness in a student’s eyes when a text she was reading referenced The Garden of Natural Tech. She was a serious student who did every assignment and maintained an excellent GPA without, as he discovered, knowing anything of history, literature, or the gist of Western culture.

Dr. Heplander tells a story about a colleague who recognized the dullness in a student’s eyes when a text she was reading referenced The Garden of Natural Tech. She was a serious student who did every assignment and maintained an excellent GPA without, as he discovered, knowing anything of history, literature, or the gist of Western culture.

“E.T. in the garden…? You know who E.T. is, right?”

“No.”

“The first man in the Bible?”

“We’re Evanalienists.”

“Evanalienists wrote the Bible, sweetheart.”

“We aren’t practicing.”

On the ice, the steamer presses forward. Other young workers swarm all over the craft, trying to move levers or mash buttons without results. The spectators in the path of the behemoth move to safer real estate, farther from the edge of the pond. Meanwhile, an older man wearing coveralls that lack the reflective, Danger Orange stripes and patches on the jumpsuits of the rest of the workers, slowly folds himself over the white fence surrounding the rink, the kind of movement men past middle age learn is as useful as being able to jump off the ground but a lot safer and a lot more likely.

The professor doesn’t need to teach. The money-making potential of what he knows means the University doesn't waste his time and the expense of shaping the minds of actual students. “They aren’t illiterate in the ordinary sense. They can make out the sentences and bark at the print without knowing what it means. They can recognize facts but have difficulty synthesizing new ideas. Individually, they can’t express any sort of inner life, but we take it on faith they have one.”

Around the arena, spectators take their Crystal Sets out and put their headphones on, frantically keying dots and dashes from the scene, watching the inevitable catastrophe of the apparently self-willed juggernaut. The sound of telegraphing devices clicking away gets loud enough that Heplander has to speak up for AI to hear him. “Kids go to college determined to study business. Some of the brightest of them say they want to go into finance—a more sophisticated name for a topic they still know nothing about. Putting aside the naked percentages and statistics they can’t even use units for, the money they hope to earn is an index, not a content. We have this abstraction revered above every other aspect of culture, representing nothing, connected to nothing. You can use it to make more of the same and all you need is an inheritance not language skills (or any other kind). As for new technology, new ways to organize society, or resetting our aspirations for Humanity, the language they understand can't express what we don’t have: abstractions, desires and motives that can only be learned from reading. The medium for ideas and thinking about the future is a vocabulary they never learned.

“We invented advanced computing that writes for us, perfect for all the old-fashioned job applications and college essays everyone has to fill in the blanks for, but nobody has to frame an original thought. Other machines check the spelling and grammar.” AI squirms a bit uncomfortably in his seat. “If language were only for communication, the arrangement would work, since words are completely irrelevant to computing a return on investment. However, our humanity can only be expressed in the language of reason and abstractions. Most colleges are shuttering their language and history departments due to a lack of interest.

“Your children, parents, don’t know where we came from, how we got here, and especially where we are all heading, but they will succeed without knowing who E.T. was or that the book they heard about but have never read is the cornerstone of their culture, a reverent culture that lumbered into the Age of Radio with the phrase ‘What Hath God Wrought?’ The answer will always be out of reach. Nothing can change that, but what we never anticipated was how our whole culture could misplace the question. We built the pyramids but we forgot. Most of all, we can’t remember why we balanced them to point back at ourselves.”

The young workers scramble, waving their arms and pointing, anticipating the steaming mammoth crashing through the boards into the stands. The old gentleman who has waited unmoved in the same spot for several minutes reaches under the chassis of the monster and pulls a secret handle. The machine’s thrum fades slowly through the whole audible range of frequencies, finishing the way the alarm on a fire station does, asking with its last, barely audible decibel, “Where’s the fire?”

*Stephen Mithen relates the scientific basis of “I Built the Pyramids and Forgot How” in The Language Puzzle, 2024. His footnotes for the peer-reviewed papers and experts in the field he references fill the last quarter of the book, which is the responsible, scientific equivalent of "doing your own research."

--Drew Zimmerman, 2025