Any Major Dude: The Rhetoric of Steely Dan

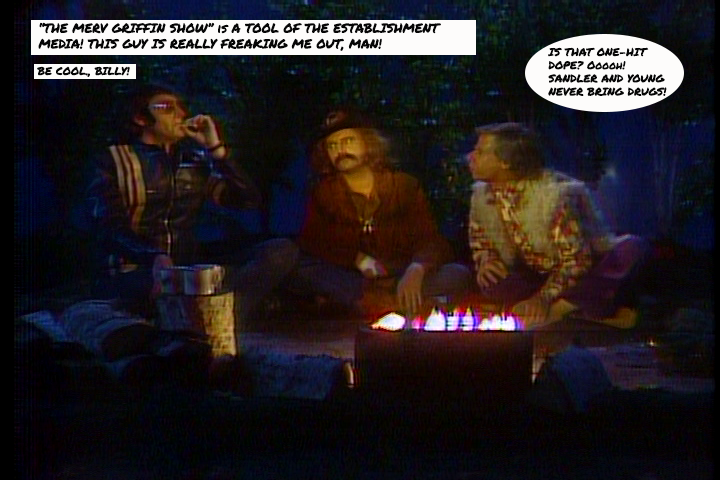

Joe Flaherty, Dave Thomas, Rick Moranis Easy Rider parody on SCTV, "The Merv Griffin Show: The 60s," NBC Television, 1981 (Shout Factory DVD).

Being hip is like being a Rosicrucian in the early 17th century. A few texts with obscure origins surface in educated society, and suddenly anyone who’s anyone claims to know the secrets of the esoteric world order. But there’s a catch. If you know the secret, the rules of the order say you can’t divulge the secret; therefore, anyone who reveals the mysteries of Rosicrucianism is a fraud. So, like, if I have to tell you the essential attitude of Steely Dan is hip, you aren’t hip and neither am I.

Steely Dan, after all, takes its name from William S. Burroughs’ firebombing, hip masterpiece Naked Lunch, and the group’s founder and lyricist, Donald Fagen, calls his memoir Eminent Hipsters. The biggest rule of hip culture–the essential of cool–-is not saying the obvious, that which need not be named. The moré of reticence comes from hip culture’s underground origins: its junkies, hustlers, anarchists, exiles, and fugitives keep mum and lay low. To give up any information could queer the whole deal, so if you know anything at all, don’t say nothing. I think that’s from earlier than Burroughs-- it’s in Wittgenstein's Tractatus.

Take John Lennon in his ridiculous white Stetson hat, getting a sly pulldown from Fagen for saying all that fawning, sickeningly obvious baloney about how happy we’d be if we turned in all our possessions and loved everything, “a world become one, of salads and sun.” Fucking millionaire sellout bastard. Your word hoard descendeth upon us. If only we were happy enough to give our shit away, we’d all be happy with nothing, and if everyone loved each other, we'd all be lovable and all our problems would be gone, and for chrissakes, mate, only a fool would say that.

Supplying a counter-weight to straight culture demands an uncompromising code of conduct, like the guys in Fight Club (1999) or the ewes in Babe (1995): “To your breed be true.” That is, never give up your own in word or deed, nothing that threatens the mobility of other free brothers. So, Kid Charlemagne has to get his test tubes and scales on out of here. “The man is wise/ You are an outlaw in his eyes.” Like Paulie in GoodFellas, here’s some money, but that’s all I can do for you, and don’t come around here any more.

The code of silence applies not only in brush-ups with the law, but also ordinary exchanges. Never give advice unless it’s “Be cool.” Hipsters live in a streamlined world, not beautiful or with spandex jackets for everyone, but stripped away of all the conventions and manners of polite society, the endless con game about hard work, accountability, and the Episcopal hymnbook that keeps us grovelling on the Astroturf. Brush aside complications imposed by a vast bureaucratic warren of cubicles, cubbyholes, and cubic centimeters of death, and what’s left is the naked lunch, unpackaged and unlabelled. You do your hustle to get what you need to survive. It’s YOUR hustle, your creation. No one sells you a franchise, because what would be the fucking point of that? After you scrape together food and a warm place to sleep you do your thing, whatever that is–drugs, music, art, or naked polo, if you want. What’s keeping you? Strip away the garbage and the straight world has nothing to keep us from digging this life, which was under the rubbish all the time.

Life itself is what we’re after, self-evident and immune to rationalization. A hipster doesn’t give advice, since, if you think about it, that’s like literally telling someone what to do. Instead, the language of cool uses structural words with no content of their own to present information as divorced from a source, either the speaker or some other authority. English is full of words that provide a scaffolding for ideas and details: prepositions, for instance, that express the relationship between nouns (Over! Through! Around!) and adverbs, like however, therefore, and instead that frame the relationship between ideas. Donald Fagen’s lyrics for Steely Dan sometimes employ structural words to present content as not being an observation of the speaker, but rather manifestly present in the environment.

The best of these devices is the “any major dude will tell you” transition in the song of the same name. Rhetorically, the phrase leaves the speaker out of it. Nothing is more pathetic than some chump on a milk crate making like the prophets with his personal vision. I’m excusing Mahershalalhashbaz, son of Isaiah, because you could spout any damn nonsense with a name like that. (Aren’t you John Jacob Jingleheimer Schmidt? Boy, you are not going to believe this…) Instead, what the song has to tell you is life goes on and this, too, whatever demon is at your door and undoing your usually superfine mind, will pass. What’s worth knowing is all the usual street-level wisdom right out of Ecclesiastes, the only book in the scriptures that comes out and says the whole carnival is a waste of time and not coincidentally the only book that charted a hit on "Billboard’s TOP 100." “I can tell you all I know, the where to go, the what to do/ You can try to run but you can't hide from what's inside of you.” Take your cue from the race as a whole, its big men making with the moral platitudes and rules, applying them to everyone else, and following their lowest impulses down to the whips and chains.

Up and down their catalog, Steely Dan’s lyrics suppress the personal point of view behind any statement, because it is far preferable to assume all the particulars are understood by the parties concerned, and no one person has privileged information they need to share. “It’s clear it’s over now,” the narrator says in “Black Cow.” meaning the reasons are too obvious to require iteration. “Unless I’m totally wrong,” says the older dude in love with another one of those slinky young things in "Almost Gothic." The speaker deprecates his opinion, because opinions are fascist. Fagen and Becker in an interview once complained that music videos attaching specific images and scenarios to pop songs are fascist, too, because they tell a listener what the song means, and that ain’t cool. In “Gaucho” the old guy who’s being played for a sucker by a slinky young thing says rhetorically, as everyone does when no explanation is possible, “Would you care to explain?”

In 1972, with the Nixon's resignation still to come and his immunity for violating all laws, legal or according to Nature, still in negotiation, Kings on Steely Dan’s debut album toasts the late King Richard and raises a glass to good King John. All kings are the same. Nixon’s corruption and arrogance doesn’t distinguish him in the least, and it’s not very cool to single out one Establishment prop from another as if it matters. The domination of the “sad old men who run this town” is a tale that goes “on and on.” To even mention it gives the stream of lies more importance than they are due. Elsewhere on Can’t Buy a Thrill (leave it to hipsters to appropriate a classic description of the depth of the one’s present blues to express irredeemable boredom), a guy from out of town suggests to Rikki that she should hold on to that “number,” because she might need it when she gets home. He isn’t “doing a number,” which means to make a pitch; he’s referring to something unnamed–a marijuana cigarette or the phone number of a hip refuge, person, or crooked doctor—through whom she can resume her “little wild time” if she freaks out back with the squares.

Steely Dan’s early albums contain songs that directly describe in group/out group distinctions, "Barrytown" for instance, which could be an account of a townie confronting one of those hippies down at the college. In "Pretzel Logic," a guy who wants a showbiz career like in the minstrel days and like he’s seen in movies and TV gets the news from somebody hipper: stardom is a prima facie sellout, and all that entertainment jazz is as out of date as your pair of platform shoes. Where DID you get them? Before long, asserting one's hip affiliation by dropping the name of someone who once was cool, like Queen of Soul Aretha Franklin, gets the Now Generation looking at you like you are crazy. Owsley didn’t get a song about him in 1976 because he was busted with 300000 hits of acid in '67. “Kid Charlemagne”’s subject is how little time it took for John Lennon’s mind guerillas (Mind Games, 1973), out there lifting the veil and stuff, to fizzle into the mists of yesteryear like the Wham-O Silly String craze and arcade Pong. Wait long enough and even hip is passè.

The death of cool, mainstream culture appropriates hipster styles and turns a philosophy of stoic detachment into a bohemian souvenir. Folks at ground zero of the 60s counterculture blast—Kesey and Jerry Garcia’s Warlock—understood the hippie thing was over by 1966 when Barbara Walters used the word on the Today Show. Whatever money touches, it corrupts, and hip is ultimately another product. Homo consumeris has such a depleted imagination they draw a complete blank when forced to express the meaning of anything in units other than dollars. In "Showbiz Kids," Steely Dan has no more meaning than Rocawear, a brand name on a t-shirt expressing the in-group status of its wearer. Fagen was way cool to bring that up. I heard a recording of the band in concert from twenty years ago, and a fan insistently shouts a request for “Showbiz Kids.” It's a very popular song!

The death of cool, mainstream culture appropriates hipster styles and turns a philosophy of stoic detachment into a bohemian souvenir. Folks at ground zero of the 60s counterculture blast—Kesey and Jerry Garcia’s Warlock—understood the hippie thing was over by 1966 when Barbara Walters used the word on the Today Show. Whatever money touches, it corrupts, and hip is ultimately another product. Homo consumeris has such a depleted imagination they draw a complete blank when forced to express the meaning of anything in units other than dollars. In "Showbiz Kids," Steely Dan has no more meaning than Rocawear, a brand name on a t-shirt expressing the in-group status of its wearer. Fagen was way cool to bring that up. I heard a recording of the band in concert from twenty years ago, and a fan insistently shouts a request for “Showbiz Kids.” It's a very popular song!

Elsewhere, Fagen’s lyrics use the rhetorical device of assuming what is being expressed is so obvious as to be not worth saying in service to ideas that pretty much demand justification. Describing the space race, the speaker says, “You know we’ve got to win.” Well, the U.S.A. did win space, and then we privatized it and handed it over to Elon Musk, who was more deserving. Ironic from beginning to end, “I.G.Y”’s dream of a totally cool and totally free future is, you’ve got to admit it, at this point in time, NOT clearly in sight. 1975’s “Chain Lightning” is about attendees at a Hitler rally. “Don’t bother to understand.” Don’t figure it out, just go with the electric vibe of the crowd. “Act casual, like you don’t care. Don’t trouble the midnight air.” Being cool describes a disaffection so complete, it even shrugs off fascism, a monolithic corporate future, and worse if the buzz is right.

Bless its multi-leveled, tax-bracketed heart, the hierarchy of power generates its own underground, the antithesis of the “It’s Morning in America’s Corporate Heartland” Scam. Beatniks! Hippies! National Lampoon! Then–perhaps not right away, but eventually–you will walk down a checkout aisle, and in a rack under the Tic-Tacs is a single-issue Time magazine naming “The Underground” as one of the year’s biggest trendmakers along with Mr. Coffee and fondue sets. It goes without saying we wake up one day and humanities and decencies and even bad taste are out of fashion. Disorientation goes with old age. They call it hip replacement. But why am I telling you?

© Drew Zimmerman, 2025