David Lynch at PAFA: Why a Duck?

Describing the assignment of curating a show at the Main Line Art Center in Bryn Mawr, Julien Robson said the most useful distinction between a serious artist and a flower-pot painting amateur is that your professionals hold themselves accountable to the whole history of art. I was in that show and I loved that remark because it excludes everyone with its single, concrete but unattainable credential, ignoring technique, suffering, or a degree from a respected institute and a testimonial from the Wizard of Oz as relevant qualifiers for the coveted title.

A fellow said to me recently that he went to a Picasso exhibition, and he was so gratified to see some good old, faithful-to-life sketches in it from the master’s youth–before he went off the rails with the noses and eyes all pointing in different directions. The man was saying, “Picasso could jump through hoops if he had to, so there!” The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts' 2014 show of art by David Lynch, Unified Field, looks in on the future Palme d'Or winner when he was a student at that school from 1966-1967. It provides a record of Mr. Lynch’s development in static imagery just before he began to make films. Is the exhibit analogous to seeing a roomful of Picasso oils from before he left Spain for Paris? Was Lynch an artist by 1966? Was he one later? Did he have a Normal period like Picasso had a Blue one?

No one can claim to grasp “the whole history” of art, but essentials in the posture of the real deal, if you will, are clear. Practitioners in one medium or another forge an intellectual and physical engagement with the unknown for the purpose of communicating their presence in it. Unified Field establishes Mr. Lynch’s credentials as an artist, right there at PAFA, the third art school he abandoned, with a presentation of a personal archaeology that does indeed presage the sensibility of Blue Velvet and Eraserhead, or the television series Twin Peaks.

Mr. Lynch’s art is nothing if not inscrutable, and, to be sure, much of the modern art has an opacity about it, producing an I-don’t-have-enough-information feeling in the viewer. On the other hand, a movie that doesn’t fall all over itself trying to declare its intention is rare, and Mr. Lynch has made several of them, stories that resist interpretation or clear resolution. The mechanism for wresting a moral from the story is present: we see it in the hard-working and straight-shooting detectives in Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks,  but the plots amble towards an eventual revelation that doesn’t particularly reveal anything, or at least anything meaningful to the human sensibility. Of Eraserhead, Lynch said it was “a Philadelphia of the mind.” Thus, a baffling movie becomes that much clearer! I don't think so either, but like Philadelphia, Eraserhead is about the decline of the Industrial Age, the stubborn and inconvenient fleshiness of the human form, and the importance of good grooming.

but the plots amble towards an eventual revelation that doesn’t particularly reveal anything, or at least anything meaningful to the human sensibility. Of Eraserhead, Lynch said it was “a Philadelphia of the mind.” Thus, a baffling movie becomes that much clearer! I don't think so either, but like Philadelphia, Eraserhead is about the decline of the Industrial Age, the stubborn and inconvenient fleshiness of the human form, and the importance of good grooming.

Dismissing the Hollywood preference for stories with a plain solution, Lynch the movie-maker explains how, as much as we arm ourselves with facts and measurements, we don’t understand what’s going on, and even the most banal scenes and locations are fraught with cosmos-sized perils. Twin Peaks strips away layer after layer of an insidious evil infecting a whole town, and calls it "Bob." Bob turns up in the PAFA exhibit, too, but not inside the picture frames or hanging from the hooks. He is the unstated presence of unreasoning violence beneath the veneer of normalcy.

Despite the promise of its title, Unified Field doesn’t tell us what it's all about. The title of the collection refers to a branch of physics that attempts to discover the Theory of Everything, a single background of sums and data that unifies the four atomic forces: gravity, strong interaction, weak interaction, and electromagnetism. So far every attempt at finding this Golden Ratio has failed; even at the level of pure math and science, the calculations don't work. String theory as an explanation has yet to be discredited, but it presumes an order of randomness and multiplicity that’s anathema to a unified anything.

A vanity is the belief that the human mind can grasp what the universe means. One should still take a scientific approach to collect the data, but be content that science can’t explain nature in ways that will yield to human reason. Lynch on art said, “You can learn a lot by studying a duck.” Given to us by natural selection, the composition of duckiness is unsatisfying, all lopsided and cartoonish, but since the duck is a form created by evolution, we understand it is perfect. Eight billion years of evolution can’t be wrong. Lynch’s work explores a margin of aesthetics and observation that thwarts the human desire for closure and balance and ignores its native discomfort with randomness. And yet, “It’s art!” A recognizable facet of the human condition represented in metaphor.

David Lynch has made it clear over time that Philadelphia crystallized his understanding of art and the path he should take as creator. A particularly intense night in the studio revealed to him the idea of a painting that moves. From this he made one of the finest pieces in the PAFA show, the installation Six Men Getting Sick (1967). A projector plays a movie made with a crude camera over plaster casts of the artist wearing extravagant expressions in various states of fulfillment. A siren screams continuously. The installation graphically depicts vomit passing through six men as if they were culverts conducting life’s rejected dross, the horrific and ugly experience of a consciousness riveted to nature by illness. A doubter prays. Lynch might be using nausea as Sartre employed it, an epiphany revealing our utter aloneness, but in any case, human life is a sickness that only death cures.

Embrace the sickness. Philadelphia’s seedy, grimy, gray patina over scenes of depravity and inhumanity heightened the state of emergency the artist David Lynch craved. PAFA’s notes tell us he was simultaneously horrified and energized by life in the city. He grew up in a picture perfect suburb in Montana but developed a grim, Gahan Wilson-like consciousness about the evil under the rose bushes. I love the opening of Blue Velvet, Jeffrey Beaumont’s dad in a Hugh Beaumont/Leave it to Beaver suburb having a heart attack and falling to the ground. The camera detects the predatory bugs at the grassroots level. Home in Lynch’s paintings is where sickness arrives and a deranged man screams from the front lawn, “I Burn Pinecone and Throw In Your House!” The notes tell us David Lynch at one time had to assure reporters that his childhood was perfectly normal and safe. I think of Edgar Allan Poe and how the public invented his nightmarish history because where else could such terrible stories originate.

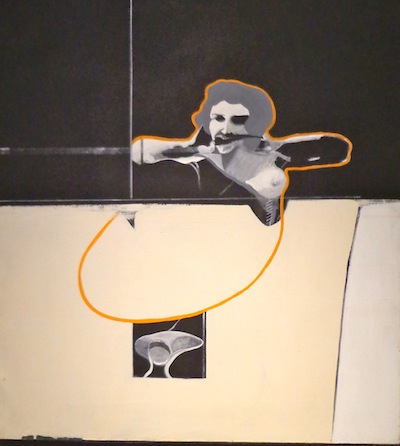

While David Lynch was at PAFA, the MoMA had its huge Francis Bacon retrospective, and a couple of the works here crib from Bacon explicitly. They have the same museum or operating theater setting and vivisectioned subjects. I spotted the open mouth and pearly white signature of England’s great, morbid portraitist, whose stated goal was doing for dentition what Monet did for haystacks. Francis Bacon’s visceral portraits of dissected humankind would have encouraged Lynch’s oddness and maybe the notoriously self-taught artist who mastered technique —but only so much technique as he needed —gave Lynch the confidence to follow the Clampetts, who were in 1966 America’s First Hillbillies, on out to Beverly Hills, swimming pools and movie stars floating in them.

Lynch’s large pieces, constructed on huge spans of cardboard with hard-wired lighting, commercial paint, and other industrial materials, are made of the flotsam that finds its way into mixed media, but here the makeshifts signal an outsider sensibility —a creepy one. I think about the art work of marginal people, who don’t know about art, Windsor and Newton art, but know what they like, and what they want, and they make it themselves: shrines, mementos, and homunculi that reference the most banal private acts of perverse cruelty imaginable. I'm thinking about Ed Gein's lady shirt and Jeffrey Daumer's throne of skulls. Several of the works in Unified Field use unwrapped cigarette filters as an artifact of an evil older than our ability to name it. Lynch communicates the unthinkable boogeyman lurking by the dumpster, behind the diner, or cruising through the neighborhood, driving too slowly.

Bacon’s Painting (1955) demonstrated the extreme viciousness and carnality of ordinary men. He does it with a confident brush, an umbrella, white teeth shiny with saliva, and a flayed carcass. The image is indelible and had its movie moment in Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs (1991). That another fine American filmmaker was influenced by Bacon is something to ponder in the rich and disturbing PAFA show of David Lynch’s works, mounted on cardboard and presaging the most disturbing images in his big screen catalog: Laura Palmer’s blue cadaver wrapped in industrial plastic and left in the park and naked Dorothy Valens running across the front lawn in Blue Velvet, interrupting her lover’s introduction of the girl next door to his horrified mom.

Qualifying someone as an artist from their work treats the title as a privilege, which it certainly is not. Handing out the title as if it were a Distinguished Service Medal signals how hard it is to attain or else anyone could call themselves an artist. In practice, the discriminating and limiting factor that determines who gets to make art and who has to paint flower pots turns out to be the unlikelihood that twenty-year-old David Lynch was even remotely hoping gallery visitors would recognize his work and grant him a creatives license. The reason he had to know the whole history of art was to learn how to express a suburban horror it had taken the whole of history to create.

You can learn a lot about art from the shape of one, odd duck.

--Drew Zimmerman, 2014