Rejecting Liberal Kitsch in Art My neighborhood has a Vinyls problem. Affluent suburbanites here spend thousands of dollars to erect Easter Island-scale monuments of kitsch. Walk in any direction and one sees holy days shrines to every icon of commercial Christmas animation–and Santa Claus, whose lineage is somewhat longer: Thomas Nast, not Rankin/Bass.

I wonder about the tiny people who own these lawns, live in these houses, who turn on the mighty fans that keep their vinyl idols upright and the spotlights that illuminate them all night long. I imagine they have some vestigial longing to celebrate humankind and a vague idea that the best way to do it is with art. This, of course, is where they flounder. Hailing the passing Range Rovers and Cayennes with creepily mute and chemical memories of trademarked, mid-60s television characters does not convey actual human experience. Is it art, does it even count as sculpture, some crappy, Jumbo-Sized inflatable that supplants fellow-feeling with a shared nostalgia for Clarice the reindeer, whose gin-blossoming sire I am prohibited from mentioning, or else pay a royalty to Gene Autry? If they weren’t so trivial, they wouldn’t need to be two stories tall to hijack my interest.

According to social media, I have 500 artist friends, and I am sure almost all of them would agree with me that the banal themes and icky materials of blow-up lawn novelties disqualify them as worthwhile art. The only thing that recommends them is they make the work of Jeff Koons unnecessary. The folks who pump air into these deflated-of-meaning monuments, using secret technology that will not become the subject of next-century, alien envoy speculation, lack the imagination to spend their money on work by an original, creative sculptor, celebrating organic human existence. As their horizons are so narrow, they communicate to the passing public with a ready-made, commercial television iconography because it is easy and instantly recognizable, or in the words of Frank Zappa, “a little bit cheesy but nicely displayed.”

So why do so many artists hook their own work to some publicly circulated, easy to understand, cause or another? I think disingenuous presenting one’s work as promoting a progressive idea in order to create an importance for the painting or sculpture other than what the work materially is and the viewer’s experience of it. I’m hoping the reason artists fall into this error is they don’t understand some indelible particulars of presentation. The use of artistic images polemically or to promote an ideology isn’t art; it’s advertising. And because emblems of a political perspective are pre-sold, their emotional impact carefully calibrated to create a particular rhetorical effect, the object is instantly kitsch: schmaltzy and predictable. Cute, but not beautiful. Appropriating images and ideas, which like coins are soiled with the patina of daily use, diminishes the thrill of encountering the unknown. I wonder if artists who frame the results of their own human journey as so much liberal kitsch aren’t lacking in confidence about their own powers of creation or the significance of their personal experience, such that they try to make their work important by linking it to some platitude about which no controversy–or curiosity–exists.

A disclaimer by me that my tastes are personal, reflective of the limited opportunities afforded to one who has never ventured out-of-body, goes without saying like the art I despise. But that’s why I think reading these words (and thank you sincerely for that!) or checking out the visual art I’ve put together or the work of any other artistic original is worthwhile. The only art that matters to me expresses the individual experience of its creator, what I always call the hand of the artist. Bored, I walk past work that illustrates the torture of Prometheus, Jesus on the Cross, the plight of a particular target of oppression, the oncoming Apocalypse, or the zero risk of a vinyl Frosty melting on my 66-degree, climate-changed lawn in mid-Atlantic December. What does any of that have to do with my experience, alone with my consciousness, trying to separate cant and custom, what’s for sale and what’s worth keeping, myth and lies from existence?

I know the world has very concrete problems with concrete solutions. My reaction to that is to vote and be kind. Expressing a liberal political position in an artwork, however exceptional the medium and skilled the technique, communicates a social cause, not the alienation of the individual trying to explain his or her own experience without any reliable signs and symbols. Slogans belong on billboards for Light Beer. If the artist can convey the message of their art with a single sentence, I’m saying that it is a vastly depleted art, lacking courage, or it wouldn’t suppress the essential human impulse beneath the pantomimes and rote exhortations.

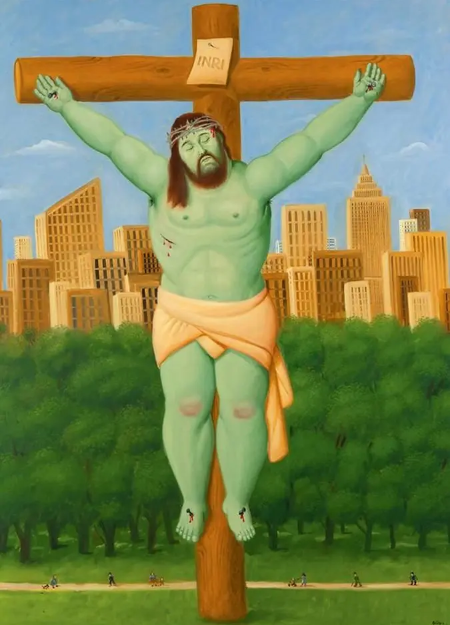

Consider Botero’s Crucifixion (2011). We cannot regard it as anything other than ironic.  This is not the use of Christ as a symbol of suffering to redeem mankind. Certainly the effect of Botero’s portrayals of the bourgeoisie as Macy’s Day floats is completely known by him to be incongruent with worshipfulness. This is Christ as kitsch, propped up in Central Park like candy floss on a stick, not as important as the towering city in the background, but equal to the dogs on leashes one meets, walking the path. In his oeuvre, Botero ironically employs the traditions of portrait painting to present the self-important people who historically were its customers. In his Crucifixion, the artist turns from directly characterizing the well-to-do to representing the supreme symbol of their religion as a Pokemon card. Alternately, when I think of the vapid crucifixion presaged in Salvadar Dali’s Last Supper (1955), hanging in the National Gallery, the failure of the work is its unabashed sentiment and the artist’s pandering imitation of faith. Surrealism as a compositional style becomes what it was destined to be: a fantasy art idiom suited to dorm room posters.

This is not the use of Christ as a symbol of suffering to redeem mankind. Certainly the effect of Botero’s portrayals of the bourgeoisie as Macy’s Day floats is completely known by him to be incongruent with worshipfulness. This is Christ as kitsch, propped up in Central Park like candy floss on a stick, not as important as the towering city in the background, but equal to the dogs on leashes one meets, walking the path. In his oeuvre, Botero ironically employs the traditions of portrait painting to present the self-important people who historically were its customers. In his Crucifixion, the artist turns from directly characterizing the well-to-do to representing the supreme symbol of their religion as a Pokemon card. Alternately, when I think of the vapid crucifixion presaged in Salvadar Dali’s Last Supper (1955), hanging in the National Gallery, the failure of the work is its unabashed sentiment and the artist’s pandering imitation of faith. Surrealism as a compositional style becomes what it was destined to be: a fantasy art idiom suited to dorm room posters.

Using a ready-made visual language, well-worn metaphors for justice, fear, awe, and suffering, the artist may as well by using emojis. Yes, yes, we know everything sucks and will continue to suck. But you–how are you getting along? Equally boring to me is art that ingratiates itself by being obviously aligned to a one-time radical and now passé art movement: Surrealism and also Pop, Conceptualism, Impressionism, Abstract Expressionism, and Futurism. Some of these have manifestos, and how Fascist is that? The group names of the rest weren’t even categories the artists applied to their own art: they were essentially “friend groups” some critic named to simplify the experimentation, the development of a private language that signifies individual difference and is mostly inscrutable, not some trite similarity that is accessible to the public and easy to sell. The first guy was expressing existential longing in an original way; all you dopes who came after him made an eight by eighteen-foot Sherwin-Williams color sample for Arctic White. The first guy was a pioneer who wanted to express the idea that one could turn an industrially manufactured object into art with body English alone. His imitators are just leaving their things around.

The very notion that in the arts one way of seeing supplants another testifies to the particular person, the particular moment in time that made from nothing an antithesis to the status quo. The idea that the passage of one aesthetic order into another is in any way progress is absurd. We’re heading laterally, not forward. The compulsion to make stuff, impractical stuff like dramatic chalk lines on a cave wall, is always the same, an opposition to the most spectacular irony of man’s 100,000s of years on Earth: while every generation inherits the same problems, over millennia the language and technology we use to express the same old same old continually evolves until we lose track of the past and can’t communicate with it. Such knowledge as man may own has to be relearned generation after generation. Here we are, stranded in time, trying to discover the meaning of humanity all over again.

At its best, the revolutionary activity of articulating an individual life–free to a point, alone to be sure–confirms the existence of other souls in an inexplicable vastness. Don’t knock it; sometimes that’s enough comfort to carry on. Our job as artists is to offer our individual testimony in a human language, recognizable as the basic yearning to express oneself, to say we were here before time obliterated personhood, culture, and every remnant of our times. A weakling myself, I praise the courage of others to face the human condition absolutely alone, and I am so sad when some other soul’s representation of their joy and spirit can be signified by the towering vinyl Santa on their front lawn or the words to a sentimental ditty everyone already knows.