Carolyn Harper Drapes a City's Invisibles in Brilliant Cloth By January of 2021, the phrase "in the middle of a pandemic" has come to express a wonder over the audacity of committing any number of mundane acts, considering. Carolyn Harper's Muse Gallery show

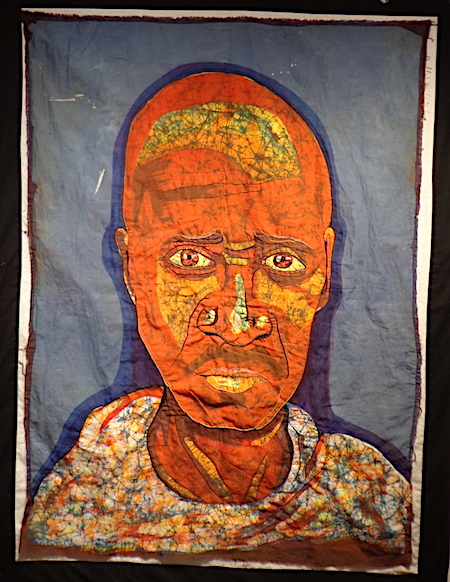

with portraits, quilted and embroidered, of homeless citizens of a stricken city ought to leave the viewer gasping at its brazen defiance, which is a refusal to set aside humanity and generosity towards our fellow man even as terror and a numbed, me-first disregard for others is one bleak subtext of the new normal.

with portraits, quilted and embroidered, of homeless citizens of a stricken city ought to leave the viewer gasping at its brazen defiance, which is a refusal to set aside humanity and generosity towards our fellow man even as terror and a numbed, me-first disregard for others is one bleak subtext of the new normal.

To be sure, the presentation of the striking collection of vivid characterizations of persons on the margins of public consciousness, whose dignity is challenged by devastating circumstance, is irregular, an improvisation appropriate to unprecedented times. A visitor to Philadelphia's oldest artists' co-operative finds Harper herself steadily embroidering a monumental fabric construction in plain view, with a section of the work stretched over a table, covered with pins, scissors, thread, and a styrofoam cup. The gallery, she says, is a more adequate studio space than she has access to when it isn't her month to mount a show. Also, the pandemic has altered Muse's usual sitting schedule; as a practicality, only the artist most intimately engaged with the exhibit has a reason to risk interaction with the occasional passerby, who must also weigh the probability of infection against the thrill of seeing masterful art in the moment of realization.

For one such daredevil, an effect of seeing the artist sewing away, masked of course, on a work that is already a striking likeness,  is that the reality it expresses has more immediacy than a work encountered in a frame, occupying the abstract space of a finished exhibit. "Yes! Here's a homeless neighbor on the pavement out-of-doors, even as we speak!"

is that the reality it expresses has more immediacy than a work encountered in a frame, occupying the abstract space of a finished exhibit. "Yes! Here's a homeless neighbor on the pavement out-of-doors, even as we speak!"

Other considerations the show brings to mind have to do with the art history context of quilting, and the decades-long rise to prominence of the homespun creations of mostly rural, mostly Southern exponents of art as necessity. The meticulously researched and lovingly curated museum shows and permanent exhibitions of quilts both gorgeous and homely are at the forefront of a movement to seize on the native imperative of everyday craftspersons who elevate typical experience to a level of meaningfulness. While we may regard the work of an artist rigorously trained in an academic environment as a step or two removed from the spontaneous compulsion to impose a human hand on the erraticisms of physical reality, the unschooled practitioner of the highly refined--yet unofficial--practice of quilting is substantially free of pretense and self-consciousness.

Harper's work has in common with the outsider quiltmakers of the South the use of fabric, that most natural and earthy of materials, and the instinctive use of art to distinguish the commonplace. Highly trained in the academic rigors of the textile artist, she has a dazzling arsenal of fabric treatments at her disposal. In some pieces, she utilizes a batik process to create a rich, multi-layered appearance to her portrait surfaces and admits that the randomness of batik's effects makes collaboration with chance part of the finished work. So much as the best modern art balances between controlling design and an appreciation of accidental, unwilled results, the sensibility behind her honest and often monumental portraits of the homeless implores the viewer to accept the cruelty of circumstances in their lives. There but for the grace of God... In the middle of a pandemic, Harper's affirmation of the dignity of those most wronged by fate makes one want to weep for the fragility of all existence and cherish especially a superbly generous gesture towards the least fortunate members of our much-threatened community.