Grandma Was Right: Mad Warped My Brain

At Grandma’s house for the weekend when I was nine, I read a 1966 Mad magazine parody of the Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor movie The Sandpipers. My favorite reading material was always inducing me to follow pop culture narratives I had no business attending, in this case, the appearance in a piece of movie fluffernutter of the most glamorous and sexy couple in Hollywood.

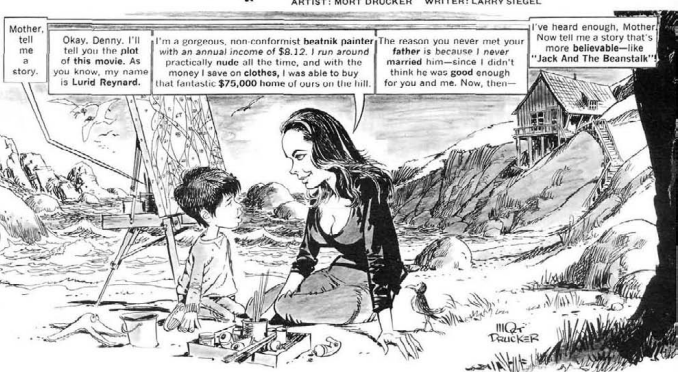

I had only just begun to figure out glamour, but I was way behind on sexy. Writer Larry Siegel’s parody was called “The Sinpiper,” a much less funny gag title than classics like “Star Blech” or “Poopside-Down Adventure,” but satire is limited by the strength of the source. The assignment was much kinder to legendary illustrator Mort Drucker who captured the likeness of LIz’s breasts perfectly.

Elizabeth Taylor and her boozy paramour Richard Burton were handed down to me from the “usual gang of idiots” at Mad. Whatever it was that made Taylor and Burton fascinating, I hadn’t a clue in third grade. Next year’s "Who the Heck is Virginia Woolf" provided a better target. This time Drucker’s caricature of sexpot Liz concentrated on her big hips and backside, and Larry Siegel’s send up of Edward Albee’s dialogue was so well remembered, it made me the star of my absurdist fiction course at the UofD in ‘77.

Having enjoyed all the really good stuff in Mad No. 101, I sifted through the leftover “departments.” I worked on "The Sinpiper" last because it held the least promise of yucks. Although I was a precocious reader, I had no idea of the connotation of mature expressions, and thus, virtually no appreciation for them. The word nude troubled me: I looked it up and didn’t understand why you couldn’t say naked.

I read the first panel aloud to my grandmother because gauging her reaction was how to learn usage: a kid asks his mother with the zowie cleavage to tell him a story. “Okay. I’ll tell you the plot of this movie,” I read to Grandma. ”My name is Lurid Reynard. I’m a gorgeous, non-conformist beatnik painter with an annual income of $8.12. I run around practically nude all the time, and with the money I save on clothes, I was able to buy that fantastic $75,000 home of ours on the hill.” [the original prosody, which never fit my own birdsong]

Although, unlike every Mad magazine ever published, I do not have on a CD-ROM of my grandmother's verbatim rebuke of my “dirty” reading material, she thought William M. Gaines’ refusal to submit his publication to the Comic Book Code was reason enough for my mother to ban the publication. My defense was, if it’s funny, it’s acceptable. Grandma Ada was not amused: “Mad will warp your brain.”

I contend she was right. Reading fundamentally changes the brain, creating cognitive routines that only exist in the decryption of text, and, in 1966, I read every word Mad magazine printed. Its vocabulary and usages were usually above my level of experience, a catalyst to my exploration of English and a major influence on my future, leading directly to the classroom where I studied Albee and absurdist fiction.

At nine, I treasured that Mad made fun of everyone–fearlessly. Mad’s writers and artists skewered the adult world that was always bugging me although I had neither the language nor experience to oppose. With the rest of the clods who were Mad’s faithful readers, I had to pursue unfamiliar vocabulary and connotation to get the jokes. The idiom is “get” instead of understand, because the laughs are underneath the word’s literal meaning in the patina of everyday use. Mad taught us Liz is naked in the shower, but she runs nude down the beach. I learned beatniks are feckless and funny, which solved Maynard G. Krebs, and I’m sure Mad originated the phrase “boozy paramour” a paragraph above.

I was conscious of some of the techniques the magazine relied on to initiate me into their humor cult. Using a ten-penny word to nail down a two-bit situation is generally funny. When he was the news anchor on SNL’s “Weekend Update,” Dennis Miller relied on baroque verbalisms to convey his snarky wit, but he only had that one pitch, which quickly became so annoying one fantasized about shoving the prop looseleaf he was pretending to read sheet by sheet past his sarcastic dental work. A more successful use of the technique is typical in bits by Monty Python. “You can’t expect to wield supreme power just ‘cause some watery tart threw a sword at you. I mean, if I went around saying I was an emperor just because some moistened bint had lobbed a scimitar at me, they'd put me away!"

Mad’s usual means of getting a laugh was to connect the name of any celebrity or historical figure to someone else, and thus invoke the sobriety--and the built-in snort-- of Dean Martin and the restraint of Jerry Lewis. Part of the utility of those sorts of references is they bind together individuals of a particular cohort who recognize each other by the names and phrases peppering their speech. I’ll use Maynard G. Krebs to mean expert in bad coffee house poetry and bongos until I stop writing, knowing full well no one remembers him, Dobie Gillis, or, for that matter, Beat poetry.

My interest in the humor of Mad magazine fueled my success as a reader while also contributing to my voice as a writer–sneering, verbose, self-deprecating, and ultimately intolerable as Dennis Miller’s. My wife Jo Ann has a Master’s in reading education, and she tells me grade level isn’t the most accurate predictor of understanding a text; interest is. I love that she knows that, but it wasn’t the first sign she was my mate for life. That was when I saw on her bookshelf a 75-cent copy of a 1968 paperback.

“Is that your copy of Mad’s Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions?”

“No! Garbage like Mad warps your brain, but the copy of Naked Lunch is mine.”

--Drew Zimmerman, 2025