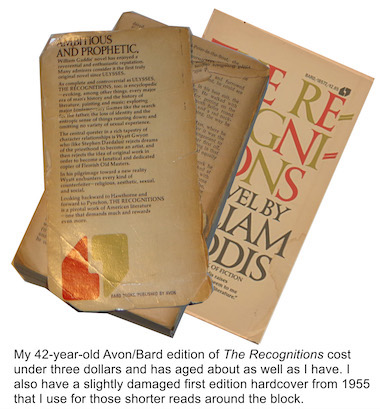

My 42 Years Reading The Recognitions

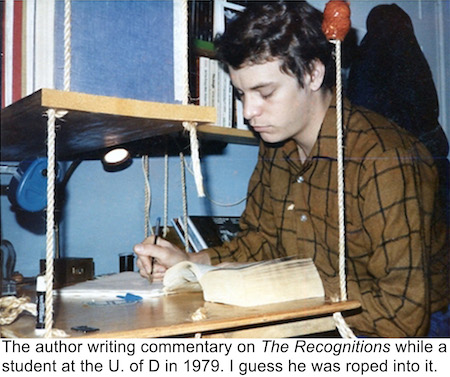

At the University of Delaware in 1979, my four years of dawdling as an English major were about to go “pffft.” Somewhere, I’m sure, a college transcript enshrines the lofty highs and leaden lows that marked my progress through about half of the courses necessary to frame a bachelor’s degree and taking twice the usual time to do it. Had I ever paid my student loans, I could actually buy a copy of that transcript today. Fanaticism (and a fair amount of alcohol)  distorted my focus in my first years as an adult. I had a notion that everything I needed to learn about writing and English had absolutely nothing to do with required courses in geography and French. My all-out commitment to literature and history courses was perfectly counterweighted by a complete indifference toward the assignments and tests of those superfluous “extra” classes.

distorted my focus in my first years as an adult. I had a notion that everything I needed to learn about writing and English had absolutely nothing to do with required courses in geography and French. My all-out commitment to literature and history courses was perfectly counterweighted by a complete indifference toward the assignments and tests of those superfluous “extra” classes.

I was practically a college dropout when I signed on to do a “special problem” in literature: one course/one semester, a sublimely refined schedule that appealed to my uncompromising lunacy. A professor of the modern novel admired my classwork and lively conversation on various absurdist writers and themes, and she put me up to what would be my last writing assignment before I left my hometown college altogether. Let me explain: in the 70s, hyper-qualified, published practitioners of practically any discipline were teaching in front of actual students at all but the flintiest institutions of learning. Today, those classes are conducted by graduate students who afford their tuition by disabusing freshmen and sophomores of the awkward notion that one may have a future in academics or the arts; however, in 1979, a genuine professor who had introduced me to John Barth, Donald Barthelme, and Edward Albee offered me three college credits to write a paper on William Gaddis’ monumental novel, The Recognitions. I guess I’ve been reading that book ever since.

In hindsight, that my first truly scholarly endeavor should be a close-reading of a 1000-page story about an everything-for-his-art ascetic who lets ordinary human relationships fall to pieces around him has a kind of inevitability. Wyatt Gwyon, the central figure in The Recognitions, possesses a superhuman facility with the tempera and religious temperament of 15th century Flemish masters, but he is prohibited by the Puritan faith of his forebears to make any original art: only God creates. With the kind of gooey, marzipan functionality by which a traditional novel resolves such dilemmas, Wyatt becomes an art forger of a very specific kind, exactly anticipating work by painters who were bound by the rules and practices of craft guilds, and whose every object on canvas was created to reflect the eye of the Almighty.

Nature is destiny, an inevitability not an opportunity. Whether from the necessities of the human form or the forms of fiction, postmodern literature often concludes that our physical being casts our fate, and free will is an amusing fantasy like dawdling over the possibility that our entire civilization rests on the head of a pin. The paper that I produced in my special problems in literature semester named the form of Gaddis’ novel as a predictor of its theme. The meaning a reader extracts from the text is conveyed less by individual actions of the characters than by author’s outrageously dense presentation of the New York arts scene after World War II. Most of the endless unraveling of the so-called plot takes place at various cocktail parties, attended by dozens of personalities whose participation in the life that art purports to represent is limited to maudlin outbursts of drink-fueled moroseness, fumbling the delivery of a new limerick that’s making the rounds, or a bitter, continuous gossip. The floating cast of regulars includes clinging women, dope addicts, and bitchy homosexuals. That’s bad, isn’t it? Maybe The Recognitions should be banned in advance, just in case high schools teach literature again.

Reading a novel that is as voluminous as some editions of the Holy Bible is like experiencing the endless, chattering dross of modern culture in real time. The comprehensive form of The Recognitions, I wrote, dramatizes the experience of time passing. Dawning in the reader’s mind is the realization that “story” itself is a quaint but silly vanity: outside the pages of a novel, nothing changes, almost nothing happens, and no one is redeemed.

Another feature of Gaddis’ epic form is the constant reminder that, despite material by the yard, characters in the novel are missing crucial information that could salvage their generally awful situations. A lattice of connections lays heavily over the story, yet the characters remain hopelessly in the dark about history essential to their own well being. Despite the omniscience wielded by so many narrators and experienced by absolutely no real person, ever, the author’s style is to not resolve missed opportunities and mistaken identities. The reader walks through a kind of maze, destined to overlook an egress in the same way that Otto, a kind of cheap imitation of Wyatt, wearing a fake arm sling and intending to meet his biological father for the first time, fails to realize that he’s taken a seat next to Frank Sinisterra, a forger looking to pass a bundle of queer bills. Frank Sinisterra, the real father of Chaby, the drug-dealing hood who is beating Otto’s time with poet, addict, and Gwyon model Esme! Frank Sinisterra, the fake ship’s doctor who killed Wyatt’s mother in a botched appendectomy, thus setting the whole concatenation in motion! In one regard, the novel’s title is ironic since its vastness and Gaddis’ stylistic reticence hide rather than illuminate likenesses.

Unlocking another set of associations for “recognitions'' describes my continuous study of Gaddis’ great American novel in the decades  since I followed Joseph R. Biden away from the campus of the University of Delaware. Determined that "Yes!" I could starve in more than one artistic discipline, by 1980 I had become a visual artist. In my first gallery appearance in 1981 on College Avenue in Newark, I showed a papiér mâché trout mask inspired by Captain Beefheart. To me, evidence of the hand of the artist is the primary attraction in a work of art. Appropriation was my metier: the reference to Don Van Vlient’s sound canvas masterpiece, Trout Mask Replica, was made with found paper, especially newsprint and advertising copy. In comparison, Wyatt Gwyon masters the tell-tale brushstrokes and compositional idiosyncrasies of classic painters who worked in a tradition that suppresses individual style. He produces entirely new work that masks his hand under the recognizable technique of another artist. With the right support from art criticism racketeers, these forgeries are promoted as hitherto unknown but recently discovered works by iconic masters.

since I followed Joseph R. Biden away from the campus of the University of Delaware. Determined that "Yes!" I could starve in more than one artistic discipline, by 1980 I had become a visual artist. In my first gallery appearance in 1981 on College Avenue in Newark, I showed a papiér mâché trout mask inspired by Captain Beefheart. To me, evidence of the hand of the artist is the primary attraction in a work of art. Appropriation was my metier: the reference to Don Van Vlient’s sound canvas masterpiece, Trout Mask Replica, was made with found paper, especially newsprint and advertising copy. In comparison, Wyatt Gwyon masters the tell-tale brushstrokes and compositional idiosyncrasies of classic painters who worked in a tradition that suppresses individual style. He produces entirely new work that masks his hand under the recognizable technique of another artist. With the right support from art criticism racketeers, these forgeries are promoted as hitherto unknown but recently discovered works by iconic masters.

No longer writing a college paper about Gaddis, I nevertheless read each of his books, identifying the signature concerns of his oeuvre, how the obsessive acquisition of money driving JR’s titular character is not “the root of all evil,” but rather what happens when the game of investing and extracting capital becomes an end and not a means. The elementary school bizwiz is truly just a kid, turning bupkis into higher-priced bupkis because “that’s what you do.” JR earned its author a National Book Award. Reading A Frolic of His Own, I learned how the technology that produced key punch cards and was essential to the computer revolution was stolen from the player piano industry. I even got an autographed copy of Gaddis’ Carpenter’s Gothic because a friend of mine used to produce an arts interview program for the BBC. Along with its idiosyncratic punctuation of human speech, the author’s work has distinctive themes, especially these two: the power of scholarship, knowing the origins of the linguistic fossils and artifacts among which we live; and the likelihood that one has missed or forgotten something essential.

Gaddis’ use of dialogue became for me an entryway to a deeper understanding of his account of the temporal landscape. Like James Joyce, Gaddis eschews the standard punctuation of dialogue, especially quotation marks: words said aloud are introduced with an em dash and never conventionally attributed to a speaker. Joyce’s great contribution to literature was his characterization of internal dialogue, the free-associating ghost in the machine that most of us connect to our genuine, secret selves. Gaddis likely admired Joyce’s presentation of a particular moment in time as containing the whole history of language, but my understanding is he rejected any suggestion that internal dialogue might be identified with our true nature or soul.

Strikingly, nowhere in The Recognitions does the reader learn the words or phrases a character is thinking. The book conveys the facial expressions of a man in deep thought (“He had the look of someone who had just taken a bite of fish and found it full of bones.”) but acknowledges no interiority. Consistent with the radical behaviorism of Skinner and his followers, Gaddis rejects the homespun notion that internal dialogue is the origin of any empirically measurable activity. Language in the private consciousness reacts to stimuli but doesn’t formulate the actions of the physical body or will an action into being. In my lifetime, for example, I have successfully given up drinking. Hell, I’ve done it more than once! If I’ve learned anything about addiction, it’s that telling yourself to end a dependency is all but pointless. When relief comes, the transformation is in the body, not the mind. The best advice you can give an addict is to ignore your self-serving, lying consciousness completely, like Ulysses putting wax in his ears.

Consciousness is where rationalization takes place, not determination, the true source of which is in the sinew and tissue collecting the scars of our battles and beatdowns. Most of us are barely in touch with the history of positive and negative consequences that, in effect, form our destiny. We translate what the body knows into language, and at best it’s a clumsy correspondence. If you don’t believe me, observe for yourself what happens when you recognize a face, a somewhere-in-the-flesh process for which any cognitive, verbal description is completely superfluous.

I have argued elsewhere that William Gaddis’ reputation as one of the first postmodern writers may likely be attributed to his ultimately gibberish presentation of dialogue in The Recognitions. About half of the book unspools as hilarious/horrific cocktail party banter, celebrating a guest who doesn’t show, toasting a host no one knows, and honking without communicating in the same circle one gaggled with at the last party and the one before that. In a traditional novel, dialogue advances the plot and reveals the nature or interior life of characters. Like the chatter constantly streaming between my ears, the conversation in Gaddis provides little more than background noise consisting of fragments of jokes, allusions to the work of unidentified artists and writers, and descriptions of places and events that get crucial facts wrong. Postmodernism ultimately describes an existence where objective facts hang in the air like a license plate collection nailed to the barn wall. Once these signs had meaning; they represented something. Now, they are the wrapping that the old values and abstractions came in, meaningless but an entertaining and absorbing use of a blank wall.

Forms of story or art, existing in the absence of necessity, characterize what we oxy-moronically call “postmodernism.” Consider that the necessity of a painting by Hugo Van der Goes in the 15th century was to capture a likeness of a particular model in a very specific space and time. The artist mixes colors, poses the model, and applies paint to canvas with the single-minded intention of capturing an objectively understood image, recognizable to consumers of the painting and to God Himself. Modernism in fiction (Joyce, Woolf, Faulkner) and painting (Picasso, de Kooning, O’Keeffe) supplants God with spirituality and extends the categories of an acceptable subject to include the subjective life of the mind, but meaning is still possible. The artist marshals her talent to represent a verifiable “other,” recognizable to all. After modernism, the forms of expression continue as always but they no longer stand for an objective or even a necessarily intelligible reality. Accident replaces necessity; thus Max, Gaddis’ successful painter/author, hangs an actual worker’s paint-stained shirt in a frame, and nobody knows what it is, but they know what they like.

When I write that consciousness is not formative of behavior, the reader ought to realize I am not diminishing the power of words. I love the logical structures one builds with sounds and syntax. That they make poor descriptions of the biological imperatives of my life (such as it is) is not to say that they do not possess admirable qualities as a thing apart from the...cosmos. I struggle to choose a final word in the last sentence that isn’t contaminated by “the life of the mind,” something truly outside the language structures we compulsively inhabit. Postmodernism teaches us the discipline of acknowledging symbols are not the thing they represent. Despising abstractions because they aren’t “real,” well, you get extra credit for that; it isn’t part of the assignment.

The visual arts have long come to terms with the elementary observation that an artist represents a subject, and that the representation pleases the eye– or pleases the mind– apart from the absolutely incontrovertible fact that handiwork, whether by Wyeth or Warhol, is not the thing itself. My wife likes to tell the story of a time we visited the Barnes Museum when it was still in Lower Merion on Latches Key Lane. In one of those galleries where some of the West’s greatest art works are displayed with all the care a 12-year-old gives to tacking a magazine photo of Justin Bieber over the bed, a woman commented on an Henri Rousseau representation of a tiger in a jungle. She knew that Rousseau is considered a “primitive,” but I think she hadn’t given much thought to what that label actually signifies.

“You can see,” she said to her companion, full of her own erudition, “that it doesn’t look like a tiger.”

“Well, no,” I muttered, perhaps out of their hearing–-I’m never sure. “For one thing, Rousseau’s tiger is flat.”

Postmodernism disciplines the effete esthetes among us against the error of demanding verisimilitude as a pre-condition for art. Language approximates rather poorly our experience of being alive; making a picture of a subject doesn’t recreate the experience of having the original at hand. Even so, these games we play to try to communicate to others our individual interactions with nature are intrinsically interesting. We enjoy how the artist moves the pieces around. In Joyce or Gaddis– or Henri Rousseau, for that matter– style is the subject, not some impossible construct purporting to be “how things really are.” That I’ve learned by reading The Recognitions what is necessary to sustain oneself in the material world is unlikely, yet its erudition, satire, and representation of the fragility of experience occupy an esteemed position in my mental life. What useful advice has John Lennon ever given me, “All you need is love”?

I could say Gaddis’ novel, by the example of the travails of its central character, encourages me to move forward in my own art and career, which I’d have to admit is a career only in the sense that I’m constantly working at it. I like that Wyatt Gwyon rejects the sensible expectations of his heritage, inheriting his father’s ministry. He does what he must do artistically. Can producing a likeness of his dead mother compensate the child for her absence? Despite denying the nature of his forebears, Wyatt never resolves the guilt he feels for breaking with Puritan tradition. He imitates the style of Flemish painters whose rectitude and adherence to received forms is compatible with the Puritanism he was supposed to have left behind.

The Recognitions completely trashes the notion that business and art are compatible. The advertising executive whom Esther lives with when Wyatt does what Wyatt must do finds her ex’s copy of The Lives of the Saints and is thrilled with the prospect of turning it into a commercial entertainment, no doubt with the abortion pill for which his agency has the account as a sponsor. The dealer who profits from Wyatt’s forgeries is one Recktall Brown, represented as having a stark likeness to a pig. He is the kind who repackages a two cents per gallon cleaning fluid in six-ounce bottles and charges a thousand percent mark-up. Gaddis’ outline of the man is nearly as allegorical as John Bunyan characters with names like “Pilgrim” and “Hypocrisy.”

Once Wyatt’s work commands impossible sums of that ill begotten money, the unused cash piles up in his squalid studio. I thought about Alberto Giacometti, whose heyday was during the time period about which Gaddis writes. The greatest known sculptor of the twentieth century lived in a one-room studio shack, hidden in a Paris alley. He and his long-suffering wife slept in a loft above the filthy workspace. Late in his career, Giacometti literally had stacks of cash under the bed and no plumbing whatsoever.

The sales apparatus for original art tramples on the integrity of the artist and the cultural contribution of his or her work. We should not, therefore, equate being unknown and unsold with being untalented. Early in his career, Wyatt has completed several original canvases and is readying them for a show. A critic offers to write a favorable review in exchange for cash, and Wyatt predictably declines. The canvases remain obscure and unseen until eventually they are destroyed in a fire, an outcome consistent with Fate’s decree that Wyatt must remain anonymous. Another player in the art community, Basil Valentine is the art expert Recktall Brown enlists to provide the historical credentials for his protege’s imitations of Flemish masters. Valentine's successful hoodwink of the art experts confirms to himself his superiority over less privileged and less cultivated men. Of what use is Wyatt's integrity entangled with such vipers as these?

In the end, Gaddis’ most extensive criticism of the commercial art world comes across in the conversational fragments of which I have spoken, the overheard chatter of writers, reviewers, agents, and advertising men that unequivocally destroys all hope that the artist will be understood by the general public, so full it is of grotesque distortions, sloganeering, and lowbrow pandering. For the most part, Gaddis’ animosity towards critics anticipated their reaction to his book. While The Recognitions has been called the next great American novel after Moby Dick in recent years, it was not initially acclaimed, and its stylistic individuality was the primary cause of the negative critical response. Of course, seventy years passed between the publication of Melville’s masterpiece and when it finally received an enlightened academic assessment.

Early on in my 42 years of reading and rereading William Gaddis’ The Recognitions, I believed the author meant to condemn everything modern and secular. The comparison between Wyatt’s attention to detail and knowledge of his materials to the Abstract Expressionists celebrated in the 1951 cover story for Life magazine seemed prejudiced towards the religious rigor of the former. A rumor propagated at one of the Manhattan parties claims inherent vice of modern paint will cause the colors to decompose within a generation and these new fellows don't seem to care. Alternatively, the description of the guild-approved Flemish painters in the 1400s who made pleasing the eye of God their goal simply reeks of quality and spiritual edification. Despite these comparisons, a particular incident occuring near the start of the novel shows Gaddis’ lack of prejudice against modern art or the individual vision that is its defining characteristic.

Wyatt visits an uptown gallery to see Picasso’s roughly 7- by 11-foot Night Fishing at Antibes (1939, apparently the MoMA has it now) and is absolutely transfixed by the painting, calling the experience a recognition of illuminated truth that might happen to someone only seven times in a lifetime. Picasso creates a primal scene of a fisherman’s attempt to violently overcome a swimming fish and feed his family. A large-breasted girl with a bicycle and an ice cream cone stands on the pier awaiting the outcome. Not monochromatic like Guernica from the same period, Night Fishing uses a palette of luminous colors, with especially liquid pools of blue and aqua. The representational style, however, is similar to the expression of violence and outrage in Picasso’s account of the bombing of a Basque village, and indeed, as Picasso finished the work, the Germans invaded Poland. Gaddis’ uses that particular piece, an expression of Picasso’s anxiety over the start of WWII and a reference to the historical periods in his own artistic output, to indicate the kind of artist Wyatt Gwyon could have been had not the combination of cruel happenstance and cold destiny intervened.

Picasso among all modern artists epitomizes the combination of an almost divine creativity and a personal mythology. The rarity of Wyatt’s rapture indicates how precious are the moments when the imperatives of life are laid bare by an artist’s ingenuity. Liberated from mundane nature (having to earn a living) and liberated from conventional ways of seeing, the artist with the means and damned obstinance to express a singular vision is greatly blessed, and equally rich is the public that recognizes the creator living anonymously among them.

--Drew Zimmerman, 02-14-2022