WHY I'M NOT ON FACEBOOK ANYMORE

I learned today, 25 Jan. 2014, that an additive in my favorite soft drink has a dangerous side effect. To make a long story short, I have to quarantine myself from Facebook posts for a period of 100 days, because I can't take the chance I'll suddenly say something crucial in the middle of a post.

To be honest, I have a few cans of the old formula stashed away, for times when I need to boost the mind's eye. I'm keeping one to finish this essay, for instance, else I end up like Dr. McCoy, staring blankly with a cold sweat at a knot of wires and connectors after the Helmet of Knowledge has worn off. Panax ginseng in large doses augments clarity of mind and offers new viewpoints on old problems and systems. What I intermittently envision through the fog and haze is a future where major improvements in technology will send the value of posts like this one soaring, a business model that isn't compatible with the social network in its current form. Perhaps not in my lifetime, but inevitably, every individual will fulfill the role of real-time documentarian of their own experience, wearing Google Glasses, or MuskOX, or some similar device to transmit sound and sight from Station Number One (we'll all think of ourselves as Station Number One by default). By then the shamed feelings of revealed narcissism that waft through Facebook will have long dissipated. On the contrary, people will believe it their duty to report every encounter with others, their boldest thoughts on any present matter, and produce the camera angle to capture them. Following the path our technology and modern life demand, we will think this splendid, efficient, and good. And so it must be.

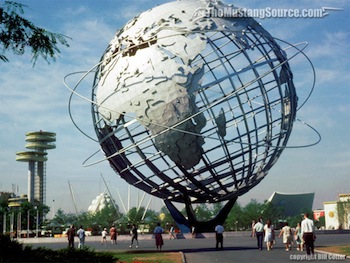

What a piece of business is man? Insisting unconvincingly on our individuality and asserting the right to privacy, deep down we've always known our existence is meaningless without incessant interaction between ourselves and other people. In the future (We earned it!), the comfort we enjoy listening to old-time space mission soundtracks, where an entity calling itself "Houston" and another "Apollo" engage in explorer-to-home-base dialogue, that feeling will be magnified, and every consciousness will feel connected to the entire "Unisphere" and the aspirations of the 1964 World's Fair at Flushing Meadows, New York, will finally be realized.

Every boomer I know who grew up east of the Mississippi made a journey with his or her family to assert at the Pepsi-Cola Pavillion, "It's a Small World After All" (though I wouldn't want to pollute it),  a sentiment that has been playing under the dark shadow of a pair of mouse ears in Anaheim, California, ever since, a source of annoyance since its vision went unfulfilled for nearly our lives entire. More than likely, after all, was the "Better Living through Chemistry" promised at the Dupont Pavilion, about which They Might Be Giants in their 1988 charttopper "Madame Ng" asked, "Why was the bench still warm from the one who had been there?" because someone had to.

a sentiment that has been playing under the dark shadow of a pair of mouse ears in Anaheim, California, ever since, a source of annoyance since its vision went unfulfilled for nearly our lives entire. More than likely, after all, was the "Better Living through Chemistry" promised at the Dupont Pavilion, about which They Might Be Giants in their 1988 charttopper "Madame Ng" asked, "Why was the bench still warm from the one who had been there?" because someone had to.

For myself, shedding the cocoon of my youth and venturing out to join the congress of other upright apes dates to a particular evening, when I was a seventeen-year-old, in a tract house development southeast of the town of Newark, Delaware. I went into the neighborhood at night and enjoyed a strange prescience of mind: instead of receiving the lights and tree cover and individual, huddled tract houses as proof of the isolation of the families who lived there, I could "see" how flimsy the barrier truly was, how thin those walls and weak those porch lights. Our yards were only a half-acre wide and deep and the fences around them served to impede but not cut-off direct motion from my house to the Singer's place, kittywampus on the same backyard strip. Linked steel bands and pickets didn't establish discrete domains of isolated Zimmermans, Crosleys, Iezzis, and Shearses. They indicated instead an already nostalgic skitterishness for the old days when we shared the same meadow or pen, like the momentary, out-of-line exuberances seen from shoulder level over a flock of sheep.

An earlier memory is stepping into a crisp fall Monday morning to see if other pre-teens were at play in the common-to-all-of-us empty lot across Harmony Road, my boyhood address. I had the sudden realization that what I was going to report to the gang about last night's Ed Sullivan Show —Plate Spinners!—was another common property to all. This was the meaning of television signals out of Philadelphia on one of six separate channels, and the strange dominance of a theater between 53rd and 54th streets on Broadway in New York City over a whole continent of synchronized viewers. A friend put it this way: we may have been in separate frame houses with shingles made of a toxic asbestos-laden dust that was still safe in the 50s, but we were each sitting on the same a priori "couch," word and abstraction. That moment presented by Ed Sullivan contained the peaceful awareness of a shared attention between myself and twenty to thirty million souls, and an insight I think one doesn't have downloading a video from NetFlix or Amazon Prime.

—Plate Spinners!—was another common property to all. This was the meaning of television signals out of Philadelphia on one of six separate channels, and the strange dominance of a theater between 53rd and 54th streets on Broadway in New York City over a whole continent of synchronized viewers. A friend put it this way: we may have been in separate frame houses with shingles made of a toxic asbestos-laden dust that was still safe in the 50s, but we were each sitting on the same a priori "couch," word and abstraction. That moment presented by Ed Sullivan contained the peaceful awareness of a shared attention between myself and twenty to thirty million souls, and an insight I think one doesn't have downloading a video from NetFlix or Amazon Prime.

Just as a species can keep locked away in its genetic material a trait that is of little use coping with the environment at hand, I found myself born with the gene for full disclosure in an age that rewarded secret maneuverers and confidence men, the age of Nixon, the Pentagon Papers, and the recipe for Colonel Sanders Chicken. In several states, they can shoot you for getting your Frisbee from the the other side of the fence out back, but I stayed philosophical about being H.G. Wells'—or Elvis Costello's —"man out of time" since I knew what is valued in one generation will soon be discarded, and that which is frivolous romanticism on Monday, may be essential nuts and bolts by the week-end.

With an impatient gesture I waved off the jeering, a suggestion my time on social media was ill-spent, because I owned the conviction that in the future, economics would reward the ability to account for one's own present with crisp, evocative prose and penetrating interpretations of that which one observes. Old-timey entertainment fictions are sprawling collaborations that require five to eight minutes to acknowlege in a crawl at the movie's end. The future—this future!— wants self-produced digital records of independent actors and their interactions with other, similarly equipped participants in a modish real, maverick "journalists," to unearth a term with no present counterpart in our language, commanding huge sums for posting self-recorded works spooled out over a single signature, or single signature style.

We have the seeds of this revolution all around us: gonzo journalism but with the hyper-subjectivity and paranoia of drug and alcohol abuse stripped away; so-called reality television that celebrates shrill consumerism; anti-corporation practitioners in every art, building public taste for an alternative to slogans and self-serving, capitalist bias. They'll use dime store equipment with not a single Panaflex in sight. An uploaded video of the neighbor's naysaying cat plays to more people than all the digitized monstrosities in the latest, bloated cornpone from James Cameron. I'm saying my sooth on behalf of millions of free-agents posting reports from an evermore discontinuous imbeded pool of reporters in an army of men and women whose dual commitments to accessibility and self will make them celebrated as once were the writers of short stories in The New Yorker and Jason Robards on Broadway or TV's "Playhouse 90."

"Language is a scalpel, not a sledgehammer," is how I used to harangue my students, and I have to hand it to the right-wing media for its success at describing every liberal initiative in terms that make it seem anathema to the working man, the precision with which those pundits use words like "entitlement," "threat," "right-to-work," "Obamacare," "socialism," and "America." But I foresee an age—maybe not by 2035 or even in this century, but it's coming—when all things with a corporate reek—especially the anti-tax toadying of media types who benefit from corporate sponsors, will be disdained by the average man. Hard it is for me to believe the capitalist excesses of my time will go unpunished forever. If an influencer with a stack of bodysuits can monetize a YouTube channel, and one can record a hit song entirely on an iPhone, how long until digital replaces Stradivarius and AI surpasses Shakespeare? As Rollerblade (1975) and Blade Runner (1982) became fulfilled prophecies of corporation plutocrats stampimg out individuality in my lifetime, let my words be true for my children's children, and my children's children's children: big manufacturer's own technology and cheap Chinese made versions of it will fuel the rage for DIY non-pros who will spread the attitude that mass corporate media is uncool.

at describing every liberal initiative in terms that make it seem anathema to the working man, the precision with which those pundits use words like "entitlement," "threat," "right-to-work," "Obamacare," "socialism," and "America." But I foresee an age—maybe not by 2035 or even in this century, but it's coming—when all things with a corporate reek—especially the anti-tax toadying of media types who benefit from corporate sponsors, will be disdained by the average man. Hard it is for me to believe the capitalist excesses of my time will go unpunished forever. If an influencer with a stack of bodysuits can monetize a YouTube channel, and one can record a hit song entirely on an iPhone, how long until digital replaces Stradivarius and AI surpasses Shakespeare? As Rollerblade (1975) and Blade Runner (1982) became fulfilled prophecies of corporation plutocrats stampimg out individuality in my lifetime, let my words be true for my children's children, and my children's children's children: big manufacturer's own technology and cheap Chinese made versions of it will fuel the rage for DIY non-pros who will spread the attitude that mass corporate media is uncool.

The primary reason besides "they suck" that will cause consumers to eventually resent and reject corporate media and embrace the mom and pop blockbuster is the continued shrinkage of markets for the press, music, movie, and broadcasting industries. While computers and software increase opportunity for independent operators a hundredfold, ravenous corporate greed creates a fragmented underclass that doesn't need to buy high-priced mass market products anymore because they are equipped to "talk among themselves."

In any case, I've got to step down from Facebook because of the visions of the future my Rockstar Diet Soda with panax ginseng, guarana, and taurine induces. In this future, we'll all be done with a banal corporate planet peopled by nothing but brand names and possessions. We'll want to lash together an Internet brimming with eyewitness accounts of adventures and field-level conditions. Joyfully we'll correlate data, an existential challenge that's at least impossible, at worst absurd. But, that's why we drink so much caffeine.

Until then, I am, as ever, pleased to be your scamp,

Drew Zimmerman, 2014