What A Clockwork Orange Suggests about Free Will

Recently, I eked out a commentary that annoyed one potential reader who wished I would write about more accessible films or at least a movie he had seen. Fine, but to give an explanation for my process of choosing art or movies to discuss—an explanation for which no one is asking—I have to think I have a different insight into the subject from most of its audience, or why take the trouble to write something, and why expect people to read it? The exchange made me take a quick inventory in my head, nevertheless, to identify a movie nearly everyone has seen and few seem to understand completely: here’s my thinking about Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971), his most challenging film.

I don’t mean it’s the hardest to watch. That would be Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999). A Clockwork Orange, I think, is practically inexplicable without some contextual information, which isn't denying it is a visual masterpiece and completely readable as a straight-up, dystopian strack, a right dobby cinny full of groodies, yarbles, and the old ultraviolence. Despite its visual appeal and truly inspired vision of a mad future dominated by Nadsat thrillseekers run amok, Kubrick’s masterpiece deserves some intellectualizing in the old mozg.

About 1973, I read the Anthony Burgess novel upon which Kubrick based the movie, and I’ve read the lengthy commentary by the author that was republished in The New Yorker in 2012. A standout statement by Anthony Burgess in the latter is his insistence that novelists are essentially entertainers, and readers shouldn’t take the words of the author as evidence of an argument in support of a particular viewpoint:

No creator of plots or personages, however great, is to be thought of as a serious thinker—not even Shakespeare. Indeed, it is hard to know what the imaginative writer really does think, since he is hidden behind his scenes and his characters. And when the characters start to think, and express their thoughts, these are not necessarily the writer’s own.

The caution to readers not to attempt to infer what the author means from how characters behave seems a bit disingenuous to me, but I’ll not flatly refute it. He wouldn’t be the first author who claimed his work acted on its own volition. I will say that Burgess, in writing the tale of a violent youth who at first gets away with murder but eventually pays for his sins, may not be advocating an idea, but he still conforms to the conventions of what reading professionals call story grammar.

Man is a storytelling creature by nature who spins tales to present a fantasy world where certain behaviors result in satisfactory punishments and certain other behaviors result in just rewards. In the same way the definition of a sentence, a noun and a verb, explains how exactly no one recognizes a complete sentence, hearers of a story feel when a story is complete. The real world doesn’t smite the wicked man and elevate the righteous, but it is a perverse story indeed that doesn’t adhere to this edifying requirement that’s at least as old as Aristotle. Perhaps Burgess didn’t have an intended message in mind for A Clockwork Orange, but so far as he writes for mainstream publication, we know he wouldn’t present a tale that in its entirety offends the sensibilities of the public.

Problematically, however, the consequences of antisocial behavior do not fall evenly upon Alex, a feature of the story that was interpreted as the glorification of violence by the London press when the movie was released. Acting murderously, Alex rules like Alexander the Great, and when he is constrained by external controls to the straight and narrow, fate punishes him with violence. Aristotles’ principles of comedy as described in Poetics require a pleasing overall effect of the play, not the balanced ledger of one character’s behaviors in particular. In a film that satirizes the question of man's ability to choose his fate, the same society Alex ravaged and was punished by graduates him to a golden vision of carnal depravities and ultraviolence without inhibitions, demonstrating the irony of free will under an intrusive government and indicating along with his lavender, Edwardian topcoat and codpiece that violence and perversion is more or less a fashion choice and not a permanent enlistment in the eternal battle between Good and Evil.

Heinous crimes by the protagonist of A Clockwork Orange go unpunished to characterize the chaos of his environment and enumerate the string of violent assaults he will later reenact as the victim instead of the perpetrator. More like the likeable but rough hero of a picaresque fiction, Alex in his criminal and reformatory episodes is no more a complete character than Christian in John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, or for that matter, MacDowell’s naive sojourner in Lindsey Anderson’s O Lucky Man! (1973). Upon his blank slate are writ the arguments for man’s free will and its deterministic alternative.

While A Clockwork Orange may seem to glorify Alex’s destructive swath through Burgess’ surreal, but completely recognizable, urban landscape, the doubled-on-itself plot, where Alex walks exactly the same path before and after his behavioral rehabilitation with completely opposite results, obeys the form of Bunyan’s edifying allegory of right and wrong from the 1600s, where things happen to the main character, not because of his willing them to. The plot and Kubrick’s visual depictions of violence so subvert ordinary expectations that the British public, stirred by the moralizing press, believed it glorified the depravity of Alex and his droogs. Particular instances of youth violence in London and elsewhere were dubbed copycat crimes, life imitating art (as if life ever imitates art). The public outcry against Kubrick’s cinematic achievement was so intense, the director, forced into the impossible position of “explaining the joke,” pulled A Clockwork Orange from British release, and it was not seen in theaters there for three decades, until after the director’s death.

Kubrick forcefully responded to the ironic suggestion that a movie about behavior modification and the origins of aberrant, antisocial actions, could itself inspire violence.

I know there are well-intentioned people who sincerely believe that films and TV contribute to violence, but almost all of the official studies of this question have concluded that there is no evidence to support this view. At the same time, I think the media tend to exploit the issue because it allows them to display and discuss the so-called harmful things from a lofty position of moral superiority.

If ever violence has been inspired by art, we have no way of knowing because we can’t read minds, but the inarguable fact is that action precedes rationalization, which in retrospect we describe as intent. Language, most human of qualities, proves the primacy of action, since it ceases to have meaning without narrating an existing past or a describing an existing present. Despite this, Pop culture historians have argued that the tone and style of A Clockwork Orange makes Kubrick the godfather of Punk, the violent musical genre that shocked the sensibilities of straight society and exalted anarchy and ugliness for its own sake, without artistic--or even melodic--justification. (I myself was so taken by Alex’s apparel that I made a paper mâché version of his work clothes for my Halloween costume in 1982, complete with bowler, codpiece, and nine-inch dicknose.) Understandably, the supremely disciplined Kubrick bristled at being made a forebear of the Sex Pistols.

Instead of intending to luridly stimulate aggression and degeneracy, Burgess’ narrative for A Clockwork Orange raises questions about the existence of free will. Does the individual have a fixed nature and fated destiny or does he choose his own path? In the New Yorker article where he denies manipulating a story to present big ideas, Burgess expresses that he did set out to write a response to behaviorist B.F. Skinner’s ideas, compiled and published in Beyond Freedom and Dignity (1971), in which the revolutionary scientist emphasizes the need for the species to re-evaluate the impact of soul, consciousness, and all that gobbledegook on the actions men take, good or evil. Burgess recalls that (although the tenets of behaviorism had circulated for decades) B. F. Skinner’s book came out at the very time that A Clockwork Orange first appeared on the screen,

a book ready to demonstrate the advantages of what we may call beneficent brainwashing. Our world is in a bad way, says Skinner, what with the problems of war, pollution of the environment, civil violence, the population explosion. Human behavior must change—that much, he says, is self-evident, and few would disagree—and in order to do this we need a technology of human behavior. We can leave out of account the inner man, the man we meet when we debate with ourselves, the hidden being concerned with God and the soul and ultimate reality.

Skinner’s radical behaviorism dispels with intention as a predicate of action, proposing that people do not formulate actions in the consciousness and then perform them with their bones and muscles; rather, without deliberation, the physical body behaves according to the rewards or punishments it has received in response to past actions, and consciousness describes instead of motivates those behaviors. Reason provides the illusion of formative resolve, but one doesn’t need to say in their gulliver, “Clobber the ptitsa in the litso with the bolshy, penis-shaped statue,” to make it happen.

Nor, Skinner would argue, do we behave in harmony with the laws of man and God due to the conditions of our souls, or, if you’re a Calvinist, a predetermined destiny of damnation or salvation. Since the origin of behavior is the environment of consequences outside the organism, the state of mind, intention, and the health of the soul are irrelevant. Alter the menu of external consequences and alter behavior. Burgess, a devout Catholic, believed the conscious will of man to do good or evil is essential to heavenly salvation; furthermore, he considered an Orwellian threat to personal freedom Skinner’s idea that society should actively organize the system of consequences affecting the individual to condition their behavioral change. Revelatory of the author’s feelings or not, the political hacks who use Alexander DeLarge as a test case for behavioral control get their comeuppance in A Clockwork Orange for denying their subject his ability to choose his own destiny. And when the incoming pol poses in the flashbulbs with Alex, wearing a broad grin next to the symbol of Big Brother’s attempt to control us, we are sure one side is as much a self-serving, opportunist gang as the other.

After Alex bonks the yoga lady with a polyurethane penis sculpture that has a really awesome throb-rocking motion when stimulated, the police close in and capture him. Off he goes to prison, but rehabilitation proves impossibly difficult. To change the gangster’s violent patterns, the prison chaplain appeals to Alex’s understanding of the state of his soul, and as we know from Skinner’s analysis, you can’t change a lad’s behavior by mucking around with his conscience. Reading the Bible fervently, Alex becomes consoled in his penitentiary isolation by the sex, the violence, and the cruelty of man to his fellow man the Good Book glorifies. Even if one places the locus of control for behavior outside an organism rather than inside, problematic is identifying which outcomes the subject will deem beneficial to himself and which he will call detrimental. People’s behaviors often seem completely unconnected to the prevalent stimulus, and “PERVERSION,” as Poe writes in his caps, “is a dominant characteristic of man’s nature.” I also enjoy employing Plato’s axiom that no man will do bad if he knows what is the good. It isn’t as useful as Poe's or as accurate, but I like to say it, anyway.

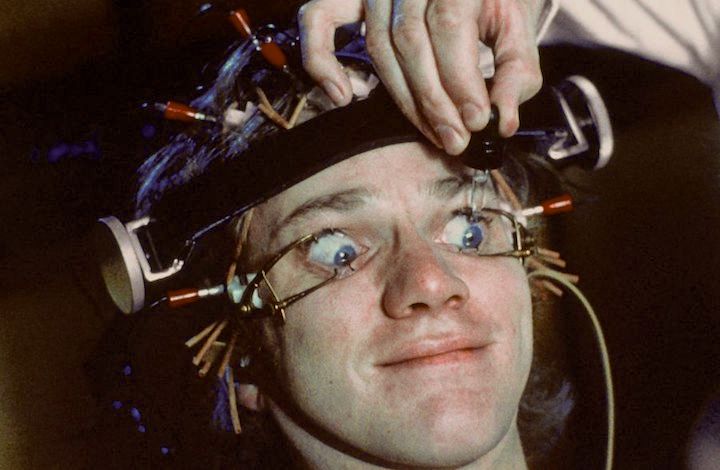

In the film, the technological solution to the input/output problem of altering behavior controls precisely what data Alex receives from his senses and exactly his visceral response to it. Laboratory technicians program the subject to become violently ill, to want to “snuff it,” in fact, when what were once enormously pleasurable stimuli, like sex and violence, appear in his external environment. The “eyes wide open” apparatus attached to actor Malcolm McDowell’s skull, forcing him to focus on prepared moving pictures of rape and murder, is perhaps the best known image in A Clockwork Orange, and it perfectly represents the state-controlled reprogramming of human behavior that Skinner predicates and Burgess abhorred. Of course, that a purely evil image of the application of exterior force to alter the will of man and coerce him to conform to societal norms instantly identifies this motion picture perversely contradicts its notoriety as the origin of Punk and inciter of random delinquency. “C’est la vie,” say the old folks, “it only proves you never can tell.”

B. F. Skinner notoriously raised his own infant children in devices that controlled their sensory input, controlled room temperature, controlled human contact. Reportedly, Skinner’s kids grew up to be fairly normal citizens. (So, was it worth it?) The great scientist recognized, I think, that his anti-Freud, counter-intuitive, model of human behavior contained terms—“environment” and “positive consequence” especially—that were difficult or impossible to define, given the complexity of the human condition. He tried to refine the experiment, but it’s impossible to inventory the exterior reality of actual, walking-around people, and thus impossible to observe or control every stimulus motivating their behavior. Additionally, differences in human perception profoundly affect individual’s predictions of how their actions will affect outcomes. In fact, the impossibility of measuring what goes on in the old mozg, dere, is a fundamental stipulation of Skinner’s entire science. For all we know about the origins of our behavior–deep in our muscle memory and the chemical labyrinths of the brain–we may as well be the puppets of fate.

As hard to survey as our inner, chemical processes are the stimuli of our behaviors in the outer world. Reality itself is a relative term, as exemplified in Burgess’ novel by the invention of a whole different language, Nadsat, to describe it. Anthony Burgess (1917-1993) was acclaimed for his brilliance in the field of linguistics, and one of his other influences on film was creating the languages used by the primitive humans in Quest for Fire (1981). With huge implications for our evolutionary adaptation, we communicate experience to one another, including our predictions of positive or negative outcomes for behaviors, using words that are so trendy as the foppish get-up Alex wears to shop for the latest fuzzy warbles by Ludwig Van at his local record shoppe. Connotations in speech are especially volatile and especially fluid, as any reader of Shakespeare’s plays who’s using an unannotated version must soon discover.

In addition to the fluidity of slanging speech, which constantly gives the old 23-Skidoo to temporary mores and public fads, the influence of new technology introduces brand-new language to convey it. Consider Kubrick’s use of Wendy Carlos’ Moog synthesizer performances of Elgar, Purcell, and Beethoven classics that are melodically consistent with the composers’ clavichord or orchestral originals, and yet morph into a form completely consistent in their radical, hyper-modern connotation with the landscape of sex and violence inhabited by Alex and his gang.

Indeed, A Clockwork Orange satirizes the inconsistency of our notions of humanity and the transient reality we inhabit. How easily we excuse vulgarity in our politicians, today, when once we believed we deserved to be led by nobility. The formal doubling over of Malcolm McDowell’s progress through the world has to do with the impact of new technology on penal science and the fleeting influence of liberal politics giving way to more conservative points of view that will be reversed again in the next election cycle. Their mayfly-like heyday dispels the idea that these political artifacts have any connection at all to national morality or the idea of humanity.

Technology proceeds from discoveries in mechanics and physics, not from literature studies and classical philosophy, yet man creates necessities to justify his inventions. We have only to consider how the existence of a hyperspace filled to bursting with digital clerks and receptionists dragged a whole people into a land where once-bedrock concepts of service, politeness, and accountability are old-timey gewgaws like the telephone booth. Who decided to forget about individual privacy, especially the safeguarding of personal space, because we have portable phones to live up to? Since we can take the electronic toy anywhere, must it then follow that we are answerable to other people, student loan police, and the DNC wherever we may roam? We are told it is foolish to look for intelligent design in nature and, what the hell, we can’t even name our own motives or how we got here. Thus, the question of whether man has a free will to choose or a fated destiny is not only irrelevant in the “how could you tell one way or the other” sense, but also because, if no intention precedes the action, how can you call this a choice?

—Drew Zimmerman, 2025